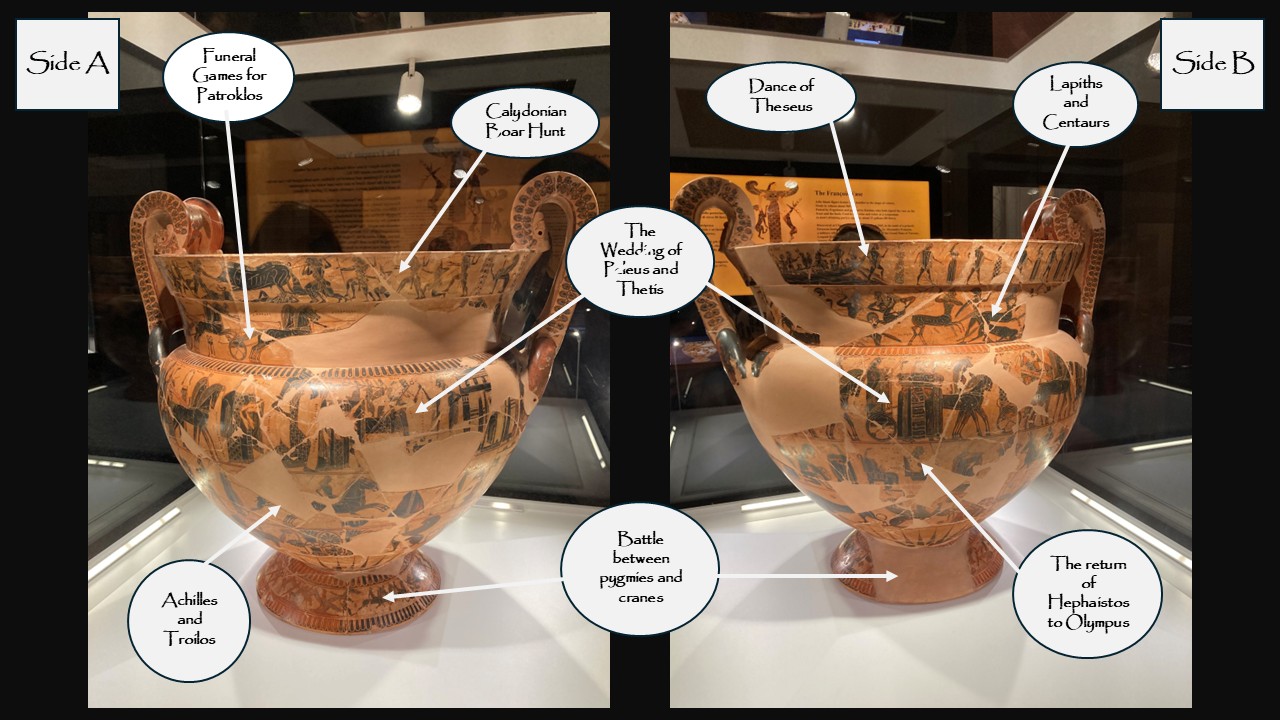

François Vase, Side A (right) and Side B (left), large Attic volute krater decorated in the black-figure style, c. 570-565 BC, Height: 66 cm, National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

Discover one of the greatest masterpieces of ancient Greek ceramics, the François Vase, a magnificent black-figure krater signed by the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias. Covered with more than two hundred finely drawn figures, it unfolds a vibrant panorama of myth: weddings, hunts, battles, heroes, and gods, all rendered with exquisite narrative clarity. This monumental vessel invites us to marvel at the artistry and storytelling brilliance that flourished in Athens during the 6th century BC, where every detail contributes to a world alive with legend and ceremony.

4 Unique Facts About the François Vase

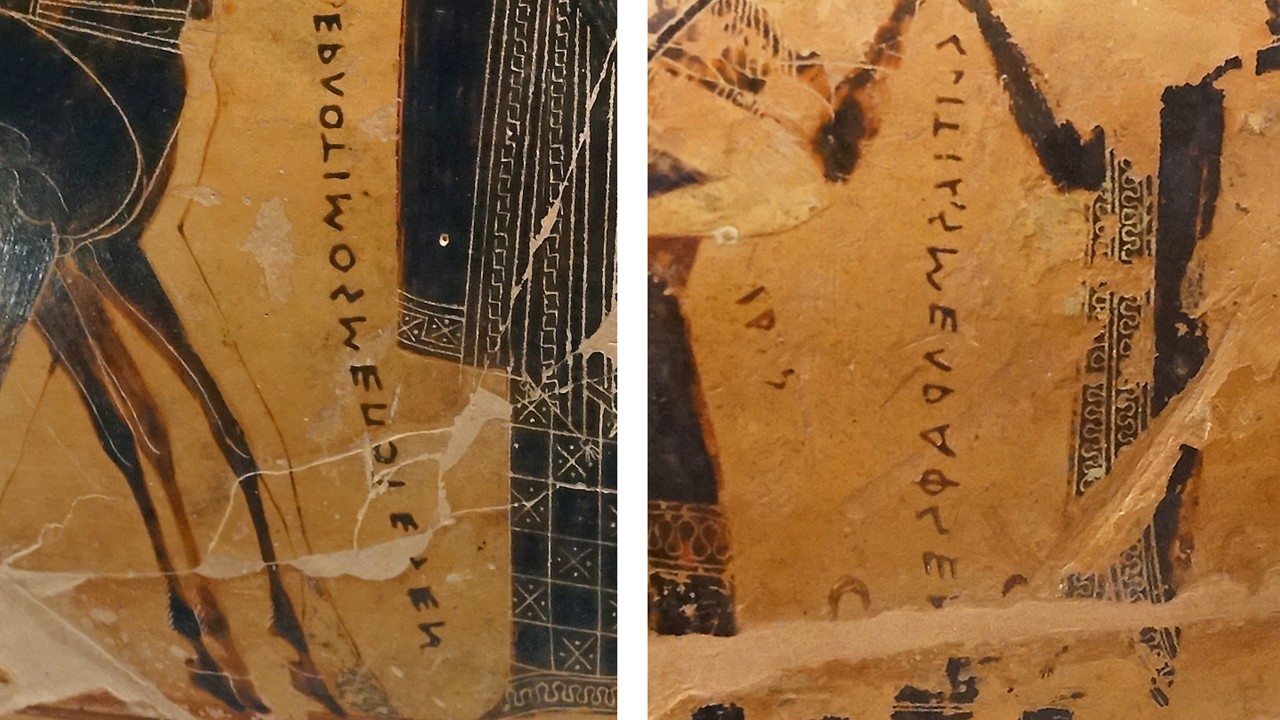

1. A Collaboration of Masters

The François Vase is signed by both its creators, Ergotimos, the potter, and Kleitias, the painter—an exceptional practice in early 6th-century BCE Athens that underscores the prestige of their collaboration. Their signatures appear proudly on the vase in Greek—ΕΡΓΟΤΙΜΟΣ Μ’ΕΠΟΙΕΣΕΝ (“Ergotimos made me”) and ΚΛΕΙΤΙΑΣ Μ’ΕΓΡΑΦΣΕΝ (“Kleitias painted me”)—asserting authorship at a moment when most artisans remained anonymous.

François Vase, Detail with painted label (left) identifies Ergotimos as the potter; painted label (right) identifies Kleitias as the painter, large Attic volute krater decorated in the black-figure style, c. 570-565 BC, Height: 66 cm, National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy https://smarthistory.org/francois-vase/

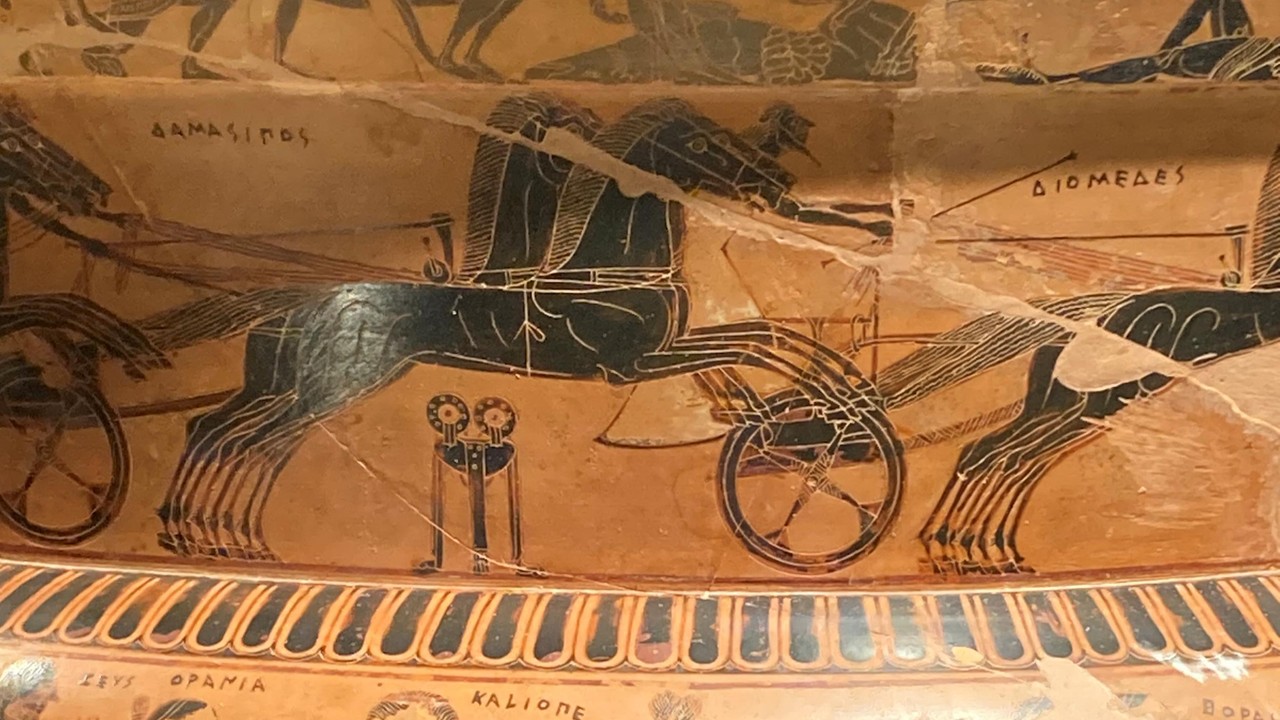

François Vase, Detail chariot race organized by Achilles in honor of Patroklos, large Attic volute krater decorated in the black-figure style, c. 570-565 BC, Height: 66 cm, National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

Ergotimos was renowned for his technical mastery, creating a large and perfectly balanced volute krater whose complex shape was articulated into seven carefully organized friezes or bands, providing an ambitious and orderly framework for visual storytelling. Kleitias, working in the Attic black-figure technique, was among the most innovative painters of his generation, populating the surface with an astonishing 270 humans, 121 of which are identified by inscriptions. His meticulous incision, use of added red and white, and deployment of boustrophedon writing, in which the direction of the text alternates from left to right and right to left, guide the viewer through densely packed mythological narratives, transforming the vase into a systematic and encyclopedic compendium of myth.

2. A Mythological Encyclopedia in Bands

The François Vase functions as a comprehensive visual encyclopedia of Greek mythology, its narratives meticulously organised into horizontal friezes or bands that allow the viewer to “read” the stories in a structured sequence from neck to foot (see image). On the neck, two friezes unfold: above, the Calydonian Boar Hunt on Side A and the dance of Theseus and the Athenian youths celebrating their escape from Crete on Side B; below, the chariot race from the funeral games for Patroklos (A) faces the battle between Lapiths and Centaurs (B). Encircling the shoulder of the vase is a continuous frieze of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, attended by a solemn procession of Olympian gods, uniting both sides in a single mythic event.

On the lower body, Side A shows Achilles in pursuit of Troilos, while Side B depicts the return of Hephaistos to Olympus, carried by Dionysos. Beneath these scenes, a lower register of sphinxes, animal combats, and palmette ornament anchors the narrative world in decorative rhythm. Even the vessel’s structural elements carry myth: the foot presents the comic yet symbolic battle between pygmies and cranes, while the handles feature Ajax bearing the body of Achilles and Artemis, the Mistress of Beasts, extending the storytelling to every surface of the krater.

3. Mastery of Black-Figure Technique

The François Vase is a prime example of the black-figure technique, in which figures are painted in black slip, with added white and purple used to distinguish female flesh and details of drapery. Details were then incised through the black slip to reveal the clay beneath, allowing for intricate depictions of anatomy, expression, and movement—bringing mythological scenes vividly to life.

François Vase, Detail with Ajax carrying the body of Achilles on the handle of the vase, large Attic volute krater decorated in the black-figure style, c. 570-565 BC, Height: 66 cm, National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, April 2025

Alongside this technical virtuosity, the vase preserves key features of the Orientalizing period, including mythological creatures such as gryphons and sphinxes, as well as exotic vegetal motifs—notably the lotus and palmette—which appear in subsidiary registers and decorative zones. These Near Eastern–inspired elements enrich the narrative imagery and reflect the cosmopolitan visual language shaping Athenian art in the early sixth century BC. Beyond gods and heroes, the vase offers glimpses of contemporary Greek society. Scenes of warriors, chariots, and domestic life reveal clothing, armor, and social customs, making it a rich historical resource as well as an artistic masterpiece.

4. A Journey Through Time

Unearthed in 1844 in an Etruscan tomb near Chiusi, the François Vase bears witness to the far-reaching cultural exchanges between Archaic Athens and Etruria, where Attic pottery was highly prized from as early as the seventh century BCE. Produced in Athens and exported to Italy—likely through major Etruscan centers such as Vulci—the vase was discovered fragmented in a chamber tomb at Fonte Rotella, already looted in antiquity, underscoring its long and complex biography even before modern times.

Following its discovery, the surviving fragments were sent to Florence and first reassembled in 1845 by the restorer Vincenzo Manni, who reconstructed the krater’s original form despite missing pieces. The vase’s modern history has been equally dramatic: in 1900, it was shattered into more than 600 fragments after a museum incident, yet painstakingly restored by Pietro Zei, who achieved an almost complete reconstruction and incorporated newly identified fragments. Further conservation followed in 1902, and again in 1973, after the devastating 1966 Florence flood caused additional damage. Today, preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Florence, the François Vase stands not only as a masterpiece of Archaic Greek art but also as a rare survivor shaped by centuries of loss, recovery, and restoration—linking the ancient Mediterranean world with modern scholarship.

The François Vase isn’t just a ceramic vessel, it’s a window into the imagination, artistry, and daily life of ancient Greece. Each figure, frieze, and inscription invites us to step into a world where myths lived vividly and storytelling was a celebrated art. Whether admired for its technical brilliance or its epic narratives, the vase continues to captivate visitors at the Archaeological Museum of Florence, reminding us that the stories of heroes and gods are as enduring as the artistry that preserves them.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of the François Vase, please… Click HERE!

If interested, explore my Blog Post titled Inspired by the François Vase… https://www.teachercurator.com/ancient-greek-art/inspired-by-the-francois-vase/

Bibliography: University of California Press E-Books: The François Vase https://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft1f59n77b&chunk.id=d0e2374&toc.depth=1&toc.id=&brand=ucpress and Florence Inferno: The François Vase https://www.florenceinferno.com/the-francois-vase/ and smarthistory: The François Vase: story book of Greek mythology https://smarthistory.org/francois-vase/