In the quiet hush of a walled garden, Sosannah, a woman of rare beauty and deeper virtue, sought solitude beneath the sun. But hidden behind aged branches and envy-clouded eyes, two elders — judges of the people — watched with corrupted hearts. When the moment came and she was alone, they emerged, casting off the mask of piety to reveal their lust. They cornered her with a cruel choice: submit to their desire or face a false accusation that would cost her life. But Sosannah, steadfast and unshaken, chose honor over life, her silence a cry to the heavens. Dragged before the assembly and condemned by perjury, her fate seemed sealed — until Daniel, youthful and divinely stirred, rose with clarity and courage. Separating the liars, he unraveled their tale with the sharp blade of truth, exposing their deceit. Justice turned its gaze, and the elders, once revered, fell by the very law they had twisted. And Sosannah, radiant in her innocence, stood free — a testament to the power of virtue and the triumph of truth… https://bible.usccb.org/bible/daniel/13

The story of Sosannah stands as a powerful symbol for the Christian Church — a portrait of moral courage, spiritual integrity, and trust in divine justice. She embodies the faithful soul, or even the Church itself, called to remain pure amid a world of temptation, false judgment, and the abuse of authority. Her unwavering stance reflects the Church’s vocation: to uphold truth and righteousness, even when isolated or under threat. In a culture that often rewards compromise, Sosannah’s quiet strength challenges believers to hold fast to virtue, trusting in God’s unseen hand.

The figures surrounding her — the corrupt elders and the righteous Daniel — deepen the symbolism. They represent, respectively, the danger of distorted power within religious institutions and the hope of divine intervention through the voice of the just. For the Church today, Sosannah’s story is less about the drama of her trial and more about the enduring truth it reveals: that God sees the heart, hears the cry of the innocent, and will ultimately vindicate the faithful. In this, Sosannah becomes not just a heroine of the past, but a guide for the present — a reminder that holiness is resilient, and truth, though buried for a time, will rise.

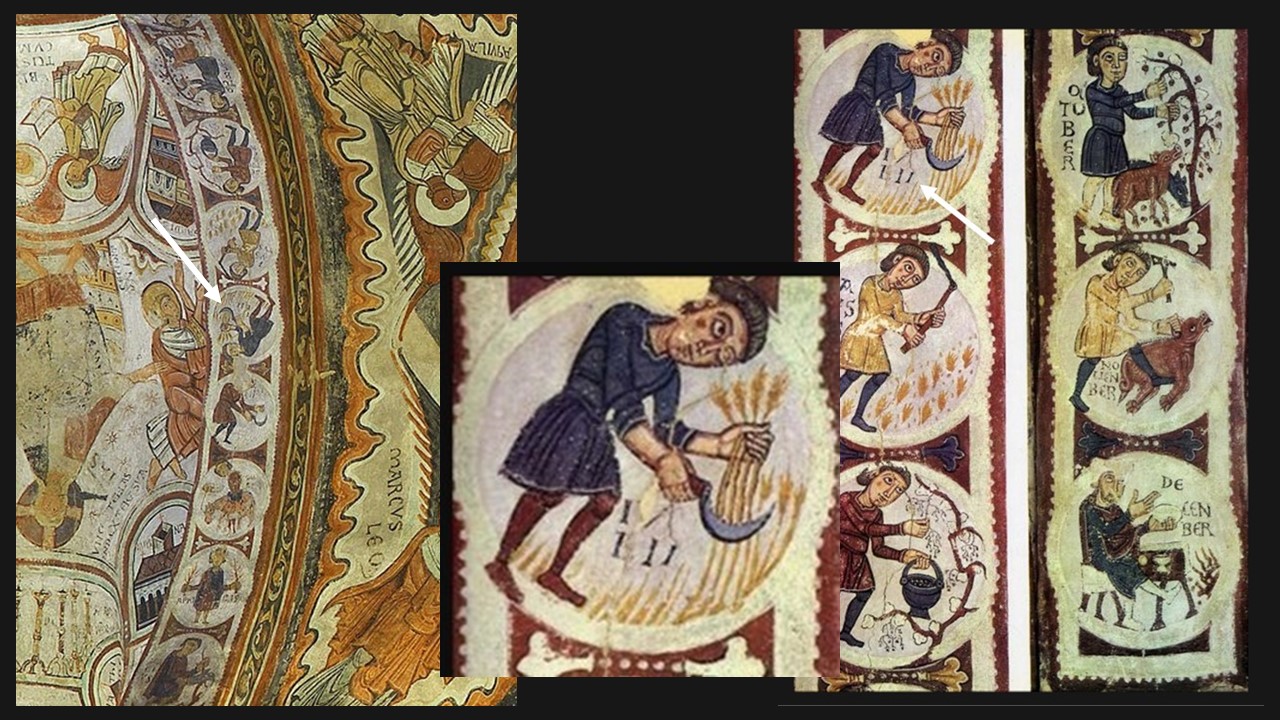

The Biblical story has inspired countless artists across centuries, drawn to its rich emotional tension and symbolic depth. In Renaissance and Baroque art especially, painters such as Rembrandt, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Tintoretto depicted the moment of confrontation in Sosannah’s garden — a scene ripe with psychological complexity. While some early depictions emphasized her beauty and vulnerability, later interpretations, particularly by women artists like Gentileschi, focused on Sosannah’s distress, resistance, and the moral corruption of the elders. These artworks often served as visual meditations on virtue under siege, the misuse of authority, and the strength of conscience. Through gestures, gazes, and the contrast of light and shadow, artists explored not only a biblical narrative but a timeless human drama — inviting viewers to contemplate justice, dignity, and divine vindication.

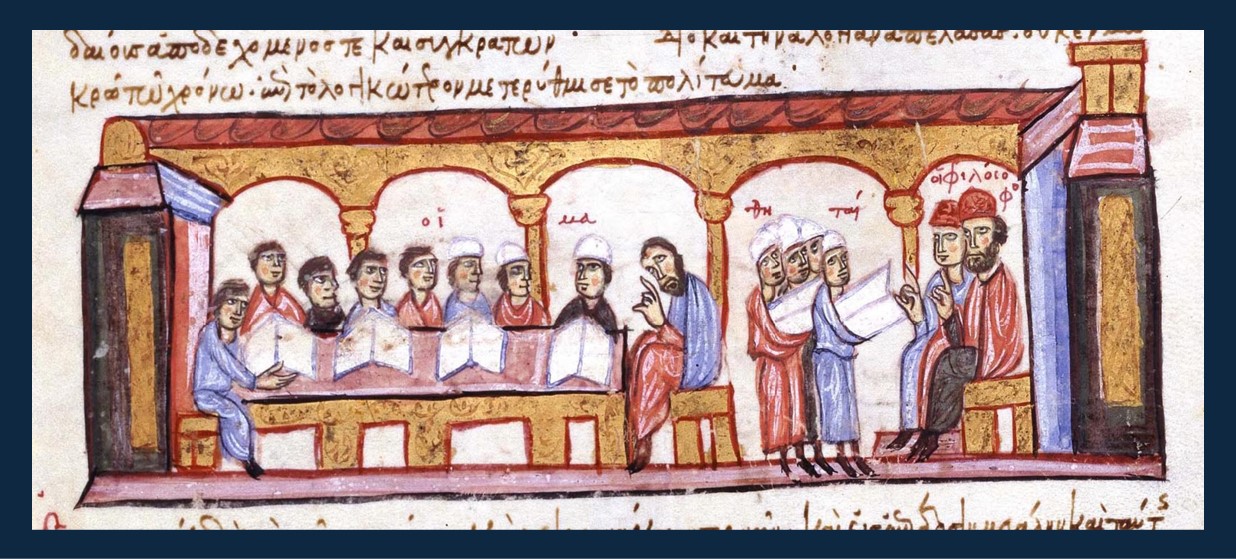

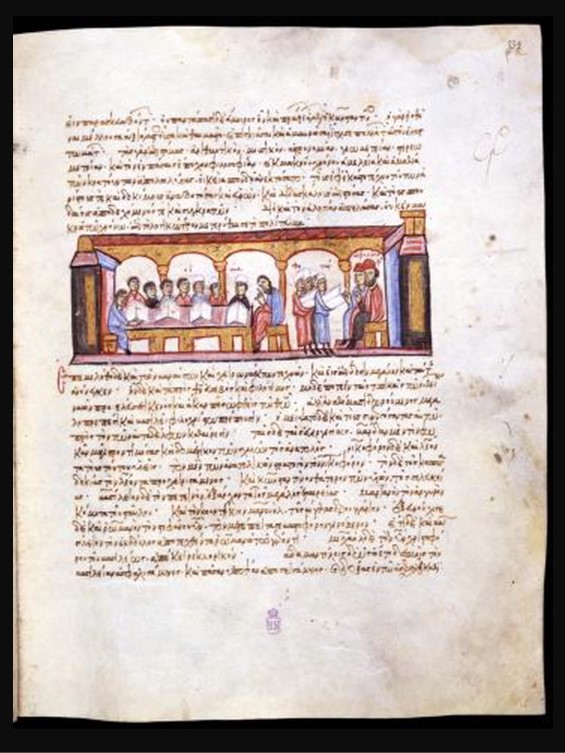

My favourite rendition of Sosannah’s story lies within the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki. It is a remarkable early Christian fresco on the west wall of a barrel-vaulted grave, presenting the biblical story of Sosannah and the Elders with both symbolic power and refined artistry. There’s something deeply moving about how this familiar biblical story comes to life through the quiet beauty of early Christian art. The composition is split into two parts: the lower register features a delicate thorakion slab with small pillars topped by pinecones — a soft, almost architectural whisper — while the upper zone bursts with meaning. There stands Sosannah, praying with solemn grace, flanked by two men whose agitation betrays their guilt. She’s framed by tall cypress trees that bend inward, as if the natural world itself leans in to witness this moment of trial and courage. Her footsteps slightly beyond the slab, reaching toward the viewer, as if inviting us to stand with her.

This fresco, dating to the fifth century, is not only a masterful example of early Christian funerary art but also a theological statement. The theme of Sosannah’s unjust accusation and divine vindication was especially resonant during a time when the Christian Church was defining its identity against the backdrop of intense doctrinal disputes and heresies. In this context, Sosannah becomes an allegory for the Church itself—pure, persecuted, and ultimately defended by divine truth. The expressive detail, naturalistic rendering of garments and foliage, and vibrant use of colour distinguish this fresco as one of the finest examples of its kind, blending artistic grace with profound spiritual symbolism.

For a PowerPoint Presentation, titled Sosannah in Painting, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: Heaven & Earth. Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, Exhibition catalogue, A. Drandaki, D. Papanikola-Bakirtzi, A.Tourta (eds), Page 71 https://www.academia.edu/43062741/_Heaven_and_Earth_Art_of_Byzantium_from_Greek_Collections_Exhibition_catalogue_A_Drandaki_D_Papanikola_Bakirtzi_A_Tourta_eds_National_Gallery_of_Art_Washington_October_3_2013_March_2_2014_and_J_Paul_Getty_Museum_Los_Angeles_April_9_August_25_2014_Athens_2013_64_123_no_10_43