Image courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/put-a-ring-on-it/

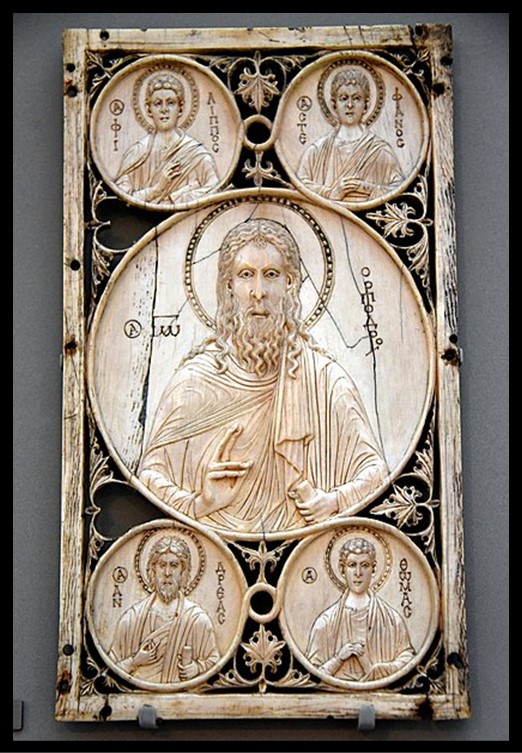

In the shimmering glow of Byzantium’s golden age, love and faith were often sealed in objects of exquisite craftsmanship and deep symbolic meaning. Among these treasures, Byzantine Engagement Rings stand as powerful tokens of devotion, not only between husband and wife but also to God. One such remarkable example is the Byzantine Engagement Ring in the Stathatos Collection, adorned with intricate enamel decoration, reflecting the era’s profound intertwining of romance and spirituality. This ring, much like the art and culture of its time, serves as a testament to a society where marriage was both a sacred bond and a reflection of divine harmony. Let us explore the beauty, symbolism, and historical significance of this extraordinary artifact.

Ashley Hilton’s Getty IRIS blog post, “Put a Ring On It,” sparked my curiosity about the deep personal and historical narratives embedded in Byzantine jewelry, particularly the Byzantine gold ring of Goudeles from the Stathatos Collection. This ring, inscribed with a dedication to a lady named Maria, serves as a tangible testament to love, devotion, and identity in the Byzantine world. Hilton’s discussion of the ring inspired me to delve deeper into its historical and social context, as well as the role of the Goudeles family in Byzantine society.

So, let’s explore the ‘who’, ‘how’ and ‘what’ of this amazing Byzantine Engagement Ring by posing some questions!

Who was Goudeles and who was Maria, and what do we know about their identity or social status in Byzantine society? The name “Goudeles” is associated with a prominent Byzantine family active from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Members of this family held various significant positions within the Byzantine Empire. The gold engagement ring from the Stathatos Collection bears an inscription (on bezel): MNHCTΡΟΝ |ΔΙΔΟΜΗΓΟΥ | ΔΕΛΗC M | AΡHA (I, Goudeles, give this engagement ring to Maria). While the exact identity of Goudeles and Maria remains uncertain, the ring’s craftsmanship and materials suggest that both the bride and the groom lived during the late 12th early 13th centuries, and belonged to wealthy and possibly influential families. For the groom, given the family’s historical prominence, it’s plausible that the Goudeles who commissioned this ring was a member of this distinguished lineage, reflecting the family’s sustained status within Byzantine society.

What was the historical significance of the Goudeles family in the Byzantine Empire? The Goudeles family was a prominent Byzantine lineage, contributing significantly to both the military and administrative sectors of the empire over several centuries. The earliest known reference to the family appears on a 10th-century lead seal, which mentions a member of the Goudeles family who held the titles of imperial protospatharios and strategos, signifying his high-ranking military status. However, the exact details of his service and the specific region he governed remain uncertain.

During the Komnenian period, one of the most notable figures was Basil Tzykandeles Goudeles, who married Eudokia Angelina, the daughter of Theodora Komnene and Constantine Angelos. This alliance linked the Goudeles family to the ruling Komnenian and Angelos dynasties, which produced emperors such as Isaac II Angelos and Alexios III Angelos.

In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Goudeles family strengthened its ties with the Palaiologan Dynasty through marriage. Among its distinguished members were Georgios Goudelis and Nicholas Goudelis. Georgios, in his testament, referred to himself as Ego Georgius Gudeles, servus prepotentis et sancti imperatoris et regis nostri (“I, George Gudeles, servant of our powerful and holy emperor and king”), reflecting his position within the Byzantine aristocracy. He served as mesazon (a chief ministerial role) under Emperors John V Palaiologos and Manuel II Palaiologos, assisting in governance and administration. Nicholas Goudeles, a diplomat in imperial service, was at one point considered for a high advisory position. During the final siege of Constantinople in 1453, he was among the defenders of the city’s Land Walls, and his fate after the city’s fall remains unknown. After the fall of Constantinople, members of the Goudeles family migrated to Italy, where they remained active in international commerce, particularly through cooperation with the maritime republic of Genoa.

Overall, the Goudeles family played a crucial role in Byzantine history, with members serving in high military, diplomatic, and administrative capacities. Their strategic alliances with ruling dynasties and their contributions to the empire’s governance reflect their lasting historical significance.

How does the design, decoration, and inscription of the Goudeles Engagement Ring in the Stathatos Collection showcase Byzantine artistry and symbolism? The Goudeles engagement ring in the Stathatos Collection is a fine example of inscribed Byzantine engagement jewelry, reflecting both artistic craftsmanship and social status. The ring’s band gradually widens to form an almost circular bezel. It is flat on the interior and slightly convex on the exterior, featuring an elaborate stylized vegetal decoration with intersecting blue spirals and green, red, and white flowers on its sides. The bezel is flat and contains a four-line inscription in blue enamel, framed within a green border. The intricate detailing, the use of precious materials, and the weight of the ring indicate that it likely belonged to a wealthy individual.

In Byzantine tradition, engagement rings (annuli pronubi), like wedding rings, were worn on the fourth digit (ring finger) of the left hand, as it was believed to have a direct connection to the heart, symbolizing eternal love and commitment. This ring exemplifies the fusion of Byzantine artistry, social hierarchy, and symbolic marital customs.

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/put-a-ring-on-it/ and https://www.doaks.org/resources/seals/byzantine-seals/BZS.1958.106.3763 and ΣΟΛΩΜΟΥ Σ. (2019). Η συμβολή της μελέτης των διαθηκών της παλαιολόγειας περιόδου στην έρευνα των κοσμικών αξιωμάτων και τιμητικών τίτλων. Byzantina Symmeikta, 29, 25–72. https://doi.org/10.12681/byzsym.15563 and https://www.academia.edu/31240474/Heaven_and_Earth_Art_of_Byzantium_from_Greek_Collections_exh_cat_National_Gallery_of_Art_Washington_DC_J_P_Getty_Museum_the_Art_Institute_of_Chicago_Athens_2013_Edited_by_A_Drandaki_A_Tourta_and_D_Papanikola_Bakirtzi