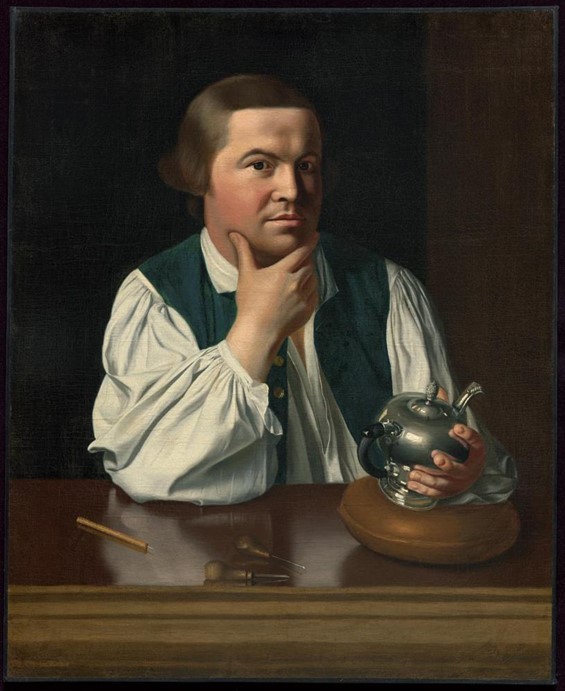

The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, c. 1789, Oil on Canvas, 56.3 x 78.8 cm, Private Collection https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6520247?ldp_breadcrumb=back

Hubert Robert’s 1789 painting, The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, masterfully intertwines the grandeur of classical antiquity with the evocative beauty of decay. By amalgamating iconic Roman structures from southern French locales, Robert crafts an imaginative landscape that transcends geographical boundaries. This composition not only showcases his artistic ingenuity but also reflects the 18th-century fascination with ruins as symbols of the passage of time and the enduring legacy of ancient civilizations.

Hubert Robert (1733–1808) was a prominent French painter, draftsman, and printmaker known for his romanticized depictions of architectural ruins. Born in Paris, he studied at the prestigious Collège de Navarre before traveling to Italy in 1754. There, he spent over a decade absorbing the grandeur of classical antiquity, training at the French Academy in Rome and studying under Giovanni Paolo Panini, a master of capriccio landscapes. Robert’s fascination with ancient architecture flourished in Italy, where he meticulously sketched the ruins of Rome, Pompeii, and Tivoli, developing a lifelong artistic theme. Upon his return to France in 1765, he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture and quickly became a favorite of aristocratic patrons, including King Louis XVI, who appointed him designer of the royal gardens. Despite the turbulence of the French Revolution—during which he was imprisoned—Robert continued to produce evocative landscapes, blending reality and imagination in his visions of the past.

Robert’s paintings epitomize the 18th-century fascination with ruins as poetic symbols of time’s passage, human ambition, and nature’s reclamation. His works frequently depict grand yet decaying architectural settings, often populated with small, contemplative figures that emphasize the vastness of history. Unlike the precise architectural renderings of his contemporaries, Robert infused his compositions with a dreamy, almost theatrical quality, using warm golden light, soft atmospheric perspective, and dynamic compositions to enhance their emotional resonance. His capriccio technique—blending real and imaginary elements—allowed him to create idealized visions of antiquity, such as The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange, and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, in which he combined multiple historical sites into a single, dramatic scene. His aesthetic influence extended beyond painting into garden design, where he applied his picturesque sensibilities to landscape planning. Ultimately, Robert’s work captures the grandeur of the past and its inevitable decline, making him one of the most poetic interpreters of ruins in European art.

Rather than depicting a single, accurate location, Robert’s painting The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange, and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence is a masterful Capriccio Painting that merges architectural grandeur with an evocative sense of decay. It creatively combines elements from major Roman sites in southern France: the Maison Carrée and Amphitheater of Nîmes, the ruins of the Pont du Gard Aqueduct, the Mausoleum of the Julii and Triumphal Arch at Glanum, located south of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence; the Triumphal Arch in Orange, and the Temple of Diana at Nîmes. The composition is carefully orchestrated to showcase these monumental structures in a dramatic interplay of light and shadow, heightening their romantic allure.

The painting exudes a melancholic yet sublime atmosphere, characteristic of Robert’s fascination with ruins as symbols of the passage of time. In the foreground, small human figures wander among the towering remnants, emphasizing the contrast between human transience and the enduring presence of antiquity. The soft, golden light filtering through broken arches and overgrown columns enhances the picturesque quality of the scene, inviting the viewer to reflect on the fragility of civilizations. Through this fusion of reality and imagination, The Ruins of Nîmes, Orange, and Saint-Rémy-de-Provence encapsulates the 18th-century admiration for antiquity and the romanticized vision of the past that defined much of Robert’s work.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Hubert Robert’s Oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6520247?ldp_breadcrumb=back and https://www.artnet.com/artists/hubert-robert/