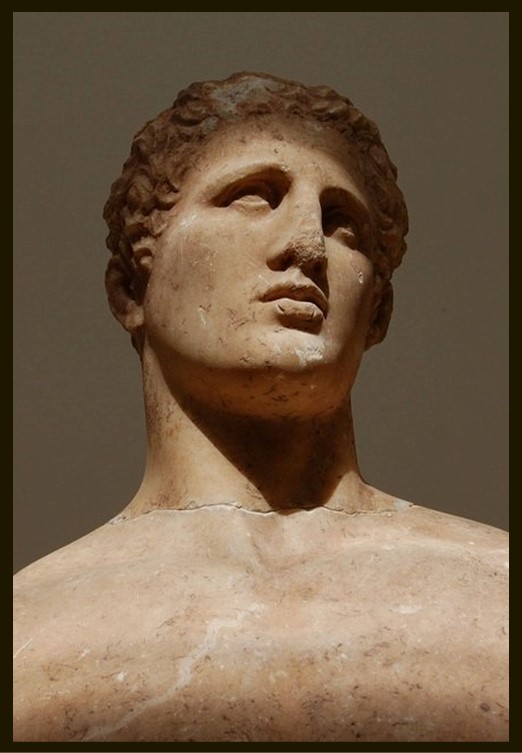

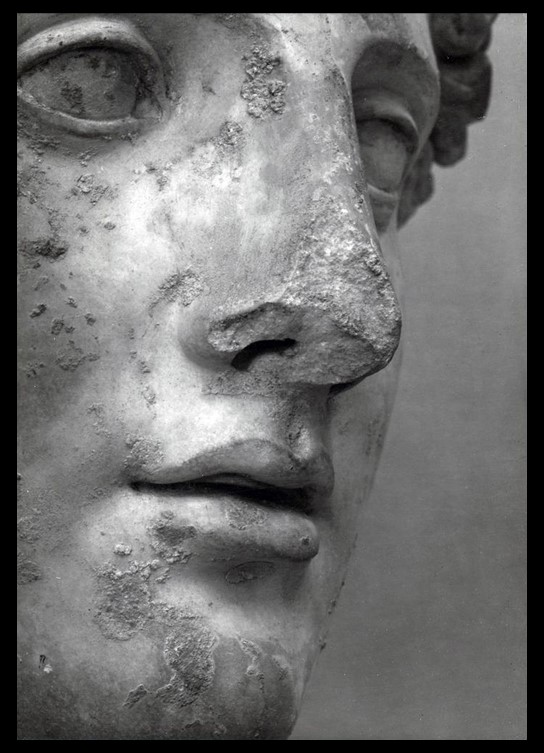

The lion sits on his haunches and looks straight ahead, with his mouth half open, evidently portrayed as growling. Anatomical details of the head have been realistically rendered. The eyes are small and fairly deeply set, the nose flat and wide. The slender, supple body and the swelling of the chest and leg muscles suggest tension. The rich mane has dense, thick, unruly curls, that were divided from each other by means of a drill. They cover the head, the upper part of the spine, the neck and the upper part of the chest. A crest of curls runs down the spinal ridge. The curls are rendered without the sharp tips that are usual on the Attic lions of the 4th century B.C. The long tail runs under the right hind leg and in snake-like curves ends in a tuft over the right haunch. This is how the Lion from a Grave Monument in the Canellopoulos Museum is described by the Museum experts, and I couldn’t agree more… https://camu.gr/en/item/epitymvio-liontari/

On the 17th of February, while visiting the Chaeronea, 2 August 338 BC: A Day That Changed the World Exhibition at the Cycladic Museum, I was captivated by the Lion from the Canellopoulos Museum. The statue’s imposing presence immediately drew my thoughts to grave monuments of lions in ancient Greek art, which are emblematic of power, courage, and enduring legacy. These sculptures, often placed atop graves, served as guardians and symbols of honour for the deceased. The lion’s fierce yet dignified expression evoked the valour of fallen warriors and the deep respect afforded to them in Greek culture. This connection underscored the lion’s role as a potent symbol across various contexts, from battlefield commemorations to funerary art, illustrating the profound layers of meaning that these majestic creatures held in ancient Greek society.

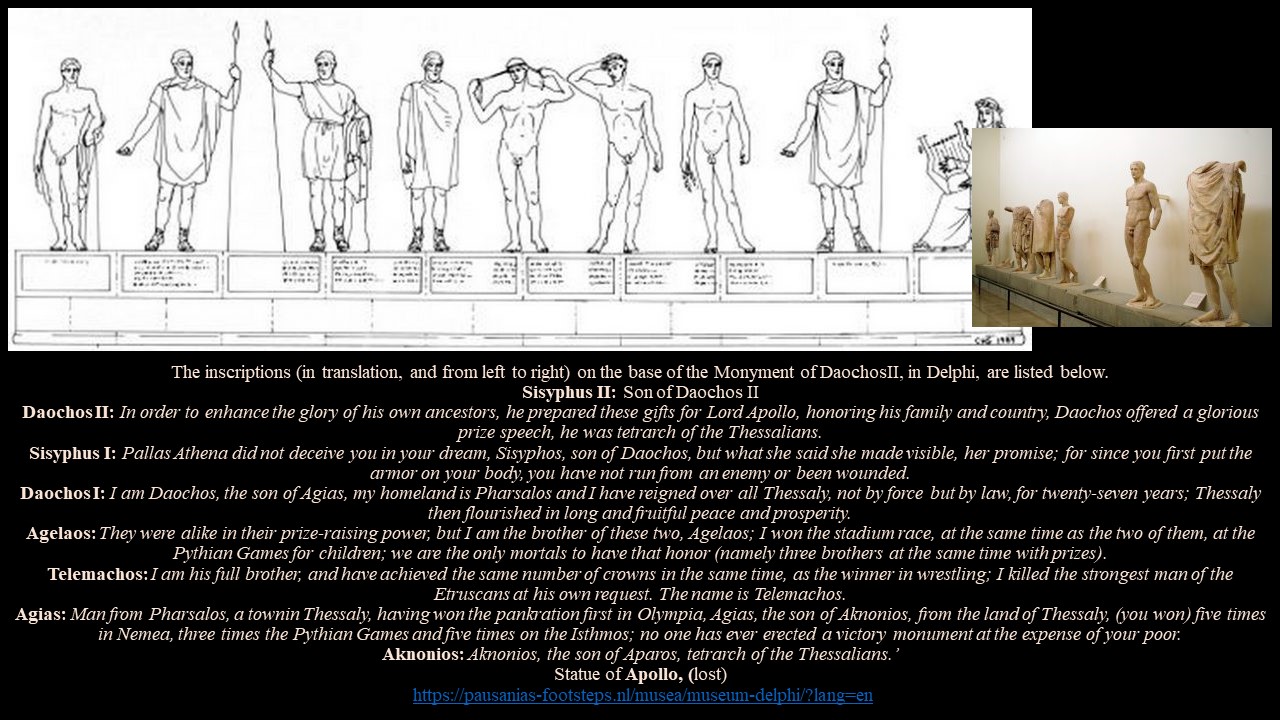

At the Chaeronea Exhibition, the Canellopoulos Lion is placed facing a sketch showing how the deceased were positioned in the Polyandrion of the Theban Sacred Band. This arrangement piques my eagerness to examine the monumental Lion of Chaeronea as well. This iconic grave monument, erected to honour the fallen Theban warriors of the Battle of Chaeronea, embodies the valour and enduring legacy of those who perished. Both sculptures’ powerful presence and dignified expression serve as a testament to the ancient Greeks’ deep reverence for their heroes, making them a compelling subject for exploration.

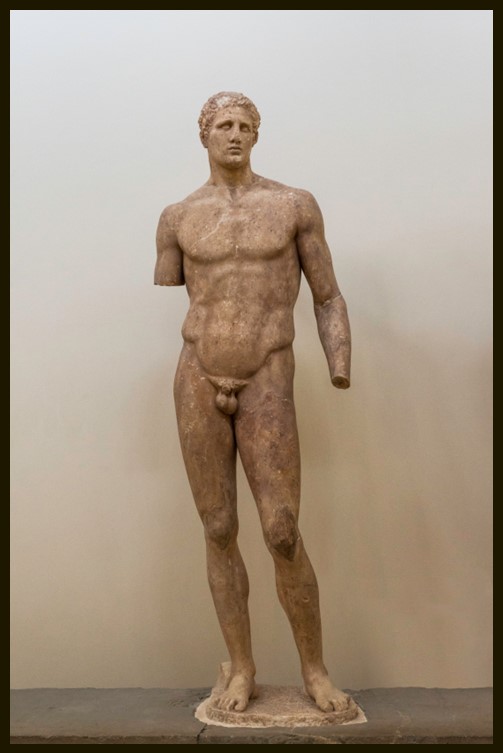

The Lion of Chaeronea stands as a significant symbol of ancient Greek history, commemorating the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, where Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great, decisively defeated the combined forces of Athens and Thebes. This battle marked the end of Greek city-states’ independence and the rise of Macedonian dominance, setting the stage for Alexander’s future conquests and the spread of Hellenistic culture. The monument is believed to honour the Sacred Band of Thebes, an elite military unit renowned for its bravery and cohesion, which was annihilated during the battle. The Lion of Chaeronea thus serves as both a memorial to the fallen soldiers and a pivotal marker of the power shift that shaped the course of Western civilization.

According to the Chaeronea Museum experts… At the entrance of Chaeronea, at a distance of 13 kilometres from the city of Livadia, stands a marble pedestal with a large lion. The tomb monument was erected in honour of the Theban soldiers of the ‘sacred band’ who fell in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, in which the Macedonians emerged victorious. When after his victory Philip II allowed the burial of the dead, the Lion of Chaeronea was erected to mark their burial place. Indeed, excavations at the site brought to light the skeletons of 254 men and some of their weapons.

The statue of the Lion is 5.30 meters tall and is depicted sitting on his hind legs. The lion is considered to symbolize the heroism of the soldiers of Thebes, which Philip II himself had recognized. The Lion was revealed after excavations in 1818, broken into five pieces. It was restored standing on a 3-meter-high pedestal. Today it is located next to the Archaeological Museum of Chaeronea, in front of a row of cypress trees.

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.mthv.gr/el/pera-apo-to-mouseio/peripatos-sti-boiotia/arhaiologiko-mouseio-haironeias-leon-tis-haironeias/#image-2 and https://camu.gr/en/item/epitymvio-liontari/