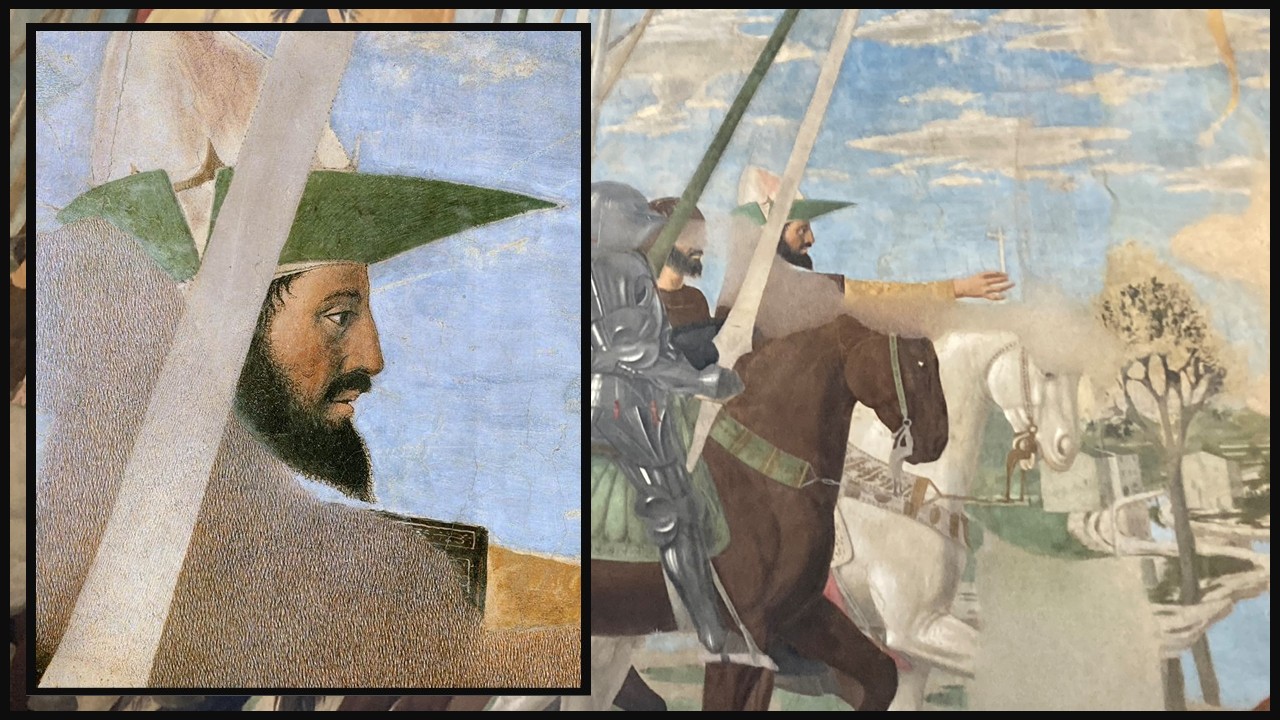

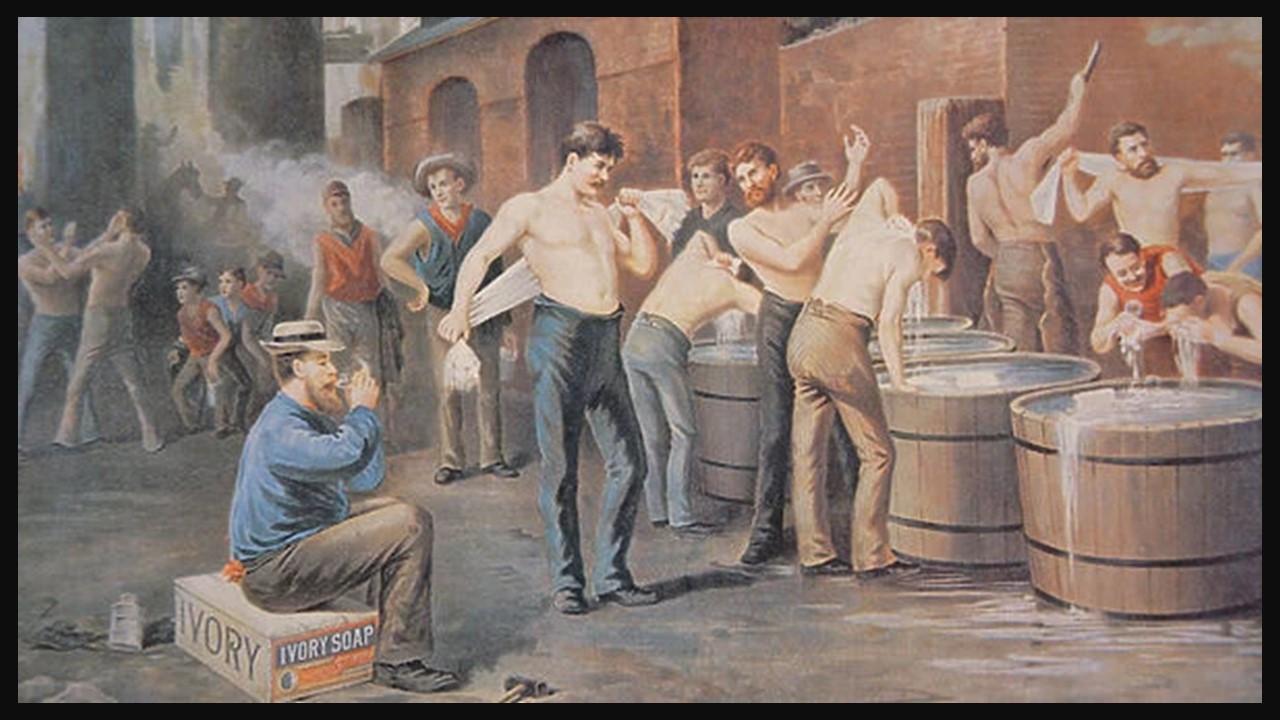

The Ironworkers’ Noontime, 1880, Oil on Canvas, 43.2 x 60.6 cm, de Young/Legion of Honor Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA, USA https://www.famsf.org/artworks/the-ironworkers-noontime

In an unexpected twist of history, Thomas Pollock Anshutz’s The Ironworkers’ Noontime, a powerful portrayal of laborers taking a rare moment of rest amidst the harsh realities of an iron mill, found itself repurposed as the centerpiece of an advertisement for Ivory Soap. This unlikely pairing of industrial grit and domestic cleanliness highlights a fascinating intersection of art and commerce, reframing the painting’s somber realism as a symbol of purity and progress. This transformation invites us to explore not just the artistic merits of Anshutz’s work but also its evolving cultural significance, as it transitioned from a poignant statement on the working class to a tool for marketing middle-class ideals.

Thomas Pollock Anshutz’s The Ironworkers’ Noontime presents a vivid snapshot of life in an industrial iron mill during the late 19th century. The painting captures a group of workers taking a break, their figures scattered across the foreground in various states of rest and conversation. The central figures are shirtless, their muscular forms accentuated by the play of light and shadow, evoking both their physical strength and the exhaustion of labor. The background is dominated by the hazy glow of molten iron and the imposing structures of the factory, subtly reminding the viewer of the workers’ demanding environment. Anshutz’s composition seamlessly integrates these human and industrial elements, drawing attention to the relationship between man and machine in this transformative era.

While Anshutz predates the formal emergence of the Ashcan School, The Ironworkers’ Noontime embodies many of its aesthetic values, making it a precursor to the movement. The painting’s gritty realism, focus on the working class, and unidealized portrayal of labor align with the Ashcan artists’ commitment to capturing the raw truths of urban and industrial life. Anshutz’s use of muted colors and dramatic lighting enhances the atmospheric tension, creating a balance between the harshness of the mill and the humanity of its workers. This empathetic yet unsentimental depiction of the labor force stands as a testament to his artistic foresight, bridging the academic traditions of his time with the emerging modernist tendencies that would later define the Ashcan ethos.

Thomas Pollock Anshutz (1851–1912) was an influential American painter and teacher, best known for his realist depictions of industrial and working-class life. Born in Newport, Kentucky, Anshutz studied art at the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. At PAFA, he became a pivotal figure under the mentorship of Thomas Eakins, with whom he shared a commitment to realism and the human figure. Anshutz’s early works reflect his meticulous academic training and a deep interest in the social and physical conditions of his subjects, which would become hallmarks of his career.

In addition to his painting, Anshutz was a celebrated teacher who influenced a generation of American artists, including members of the Ashcan School like Robert Henri and John Sloan. As a faculty member at PAFA, he succeeded Eakins as head of the school’s painting department, shaping its curriculum with a focus on direct observation and technical excellence. Though his body of work is relatively small, pieces like The Ironworkers’ Noontime stand as iconic representations of the social realist tradition in American art. Anshutz’s legacy endures not only through his paintings but also through his contributions to the development of modern American art, bridging the academic traditions of the 19th century with the expressive realism of the 20th.

The Ashcan style represents a pivotal movement in early 20th-century American art, characterized by its unvarnished depiction of urban and working-class life. Rejecting the idealized aesthetics of academic art and the genteel subjects favored by the Gilded Age, Ashcan artists focused on the gritty realities of modern cities—crowded streets, tenements, laborers, and everyday scenes imbued with raw emotion. Their use of dark, earthy tones and loose, dynamic brushwork emphasized immediacy and authenticity over polished perfection. Though Thomas Pollock Anshutz predates the formal Ashcan School, his work laid the groundwork for its ethos. Anshutz’s empathetic yet unsentimental portrayal of laborers reflects the same commitment to realism and the human condition that would define the Ashcan movement, making him an essential precursor to its development.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Thomas Pollock Anshutz’s Oeuvre, please… Check HERE!