I remember standing before the Triumph of Neptune and the Four Seasons mosaic at the Bardo Museum, in Tunisia, sunlight filtering through the high windows as if to echo the brilliance of the scene before me. Neptune, regal and commanding, surged forward in his chariot drawn by sea creatures, while the Four Seasons circled him in a dance of eternal return, each one marked by fruits, flowers, or flowing cloaks. It was as if time itself had been trapped in tesserae, inviting me to reflect on nature’s rhythms and the grandeur of ancient imagination. Today, on the first day of Summer 2025, I’m drawn back to that moment, a reminder that every season begins with awe and the quiet power of renewal.

The Triumph of Neptune and the Four Seasons mosaic was unearthed in 1902 during archaeological excavations at a Roman seaside villa in La Chebba, a coastal town in northeastern Tunisia. The excavation, carried out by archaeologists D. Novak and A. Epinat, revealed a Roman villa comprising twelve rooms, most of which were paved with mosaics of notably good style. The principal room featured a grand composition: at the center, Neptune rides over the waves, attended by two companions, while the four corners are occupied by elegant personifications of the Four Seasons. Likely serving as an atrium or formal reception space, this square, columned room showcased the opulence and artistic refinement of Roman domestic life. Dating from the mid-2nd century AD, during the reign of Antoninus Pius, the mosaic reflects the cultural and aesthetic heights achieved in Roman Africa. After its discovery, it was transferred to the Bardo National Museum in Tunis, where it remains one of the most admired treasures of the collection.

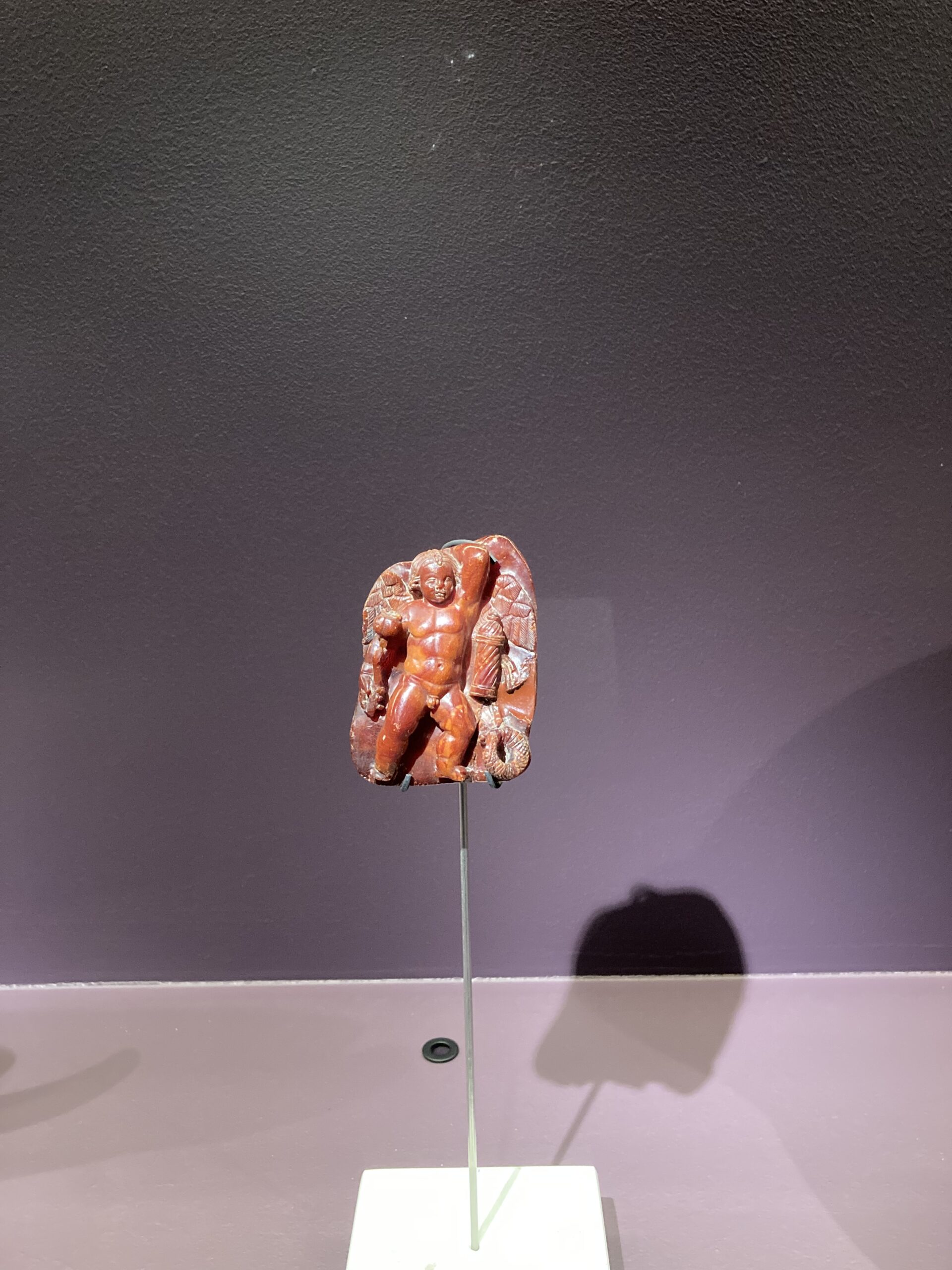

The central medallion of the mosaic from La Chebba presents a commanding depiction of Neptune, the Roman god of the sea. He stands prominently in a quadriga—a four-horse chariot—drawn by hippocamps, mythical sea creatures that are part horse and part fish. Neptune is portrayed nearly nude, showcasing a muscular physique, and is adorned with a nimbus, symbolizing his divinity. In his hands, he holds a trident and a dolphin, traditional attributes associated with his dominion over the sea. The chariot is guided by a Triton and a Nereid, both depicted partially submerged, emphasizing the marine setting of the scene. This composition, as analyzed by Gifty Ako-Adounvo in her 1991 thesis, is unique in Roman mosaic art for combining Neptune with the Four Seasons, reflecting a sophisticated iconography that intertwines themes of nature’s cycles and divine authority.

In the Tunisian mosaic, the Four Seasons are strategically placed at the four corners of the square composition, creating a visual framework around the central circular medallion that features Neptune in his marine chariot. This architectural arrangement draws the viewer’s eye inward while symbolically enclosing Neptune’s dominion within the eternal cycle of time.

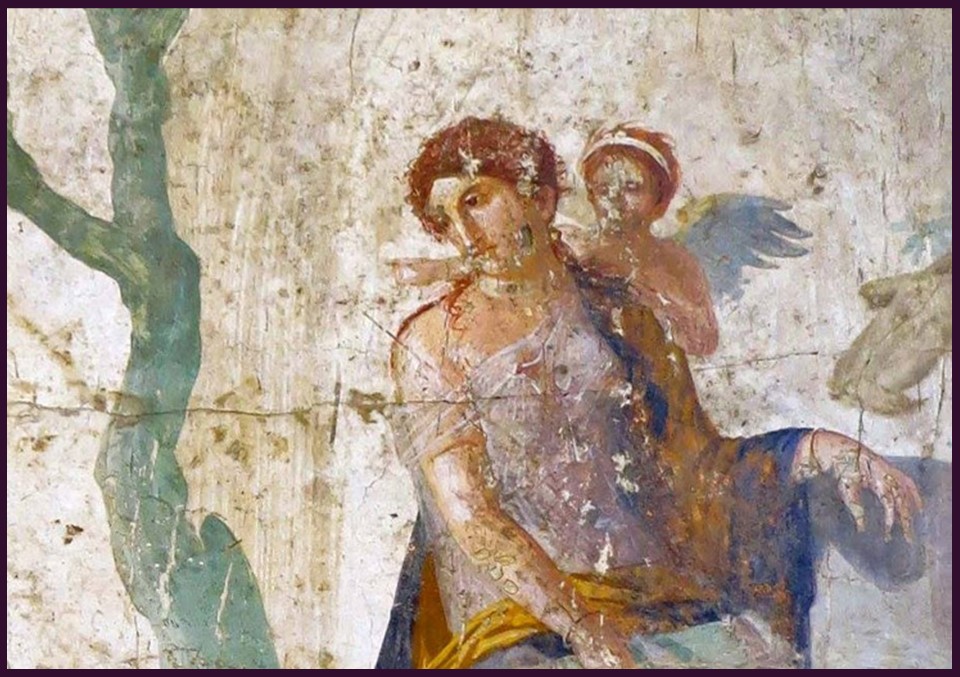

In the Triumph of Neptune and the Four Seasons mosaic from La Chebba, each Season is personified as a female figure and placed in one of the four corners of the square composition, surrounding the central medallion of Neptune. These figures are accompanied by specific animals that enrich the symbolic and seasonal imagery. Spring, adorned with floral motifs, wears a floral crown, evoking rebirth and the blossoming of nature. She is paired with a dog, possibly a greyhound, evoking themes of pastoral vitality and energy. Summer, holding sheaves of wheat, is flanked by a lion, representing the strength and intensity of the sun at its peak. Autumn, bearing grapes or a cornucopia, appears with a leopard, reinforcing the season’s association with Dionysian festivity and harvest. Winter, heavily cloaked and bearing pinecones or bare branches, is accompanied by a boar, an animal linked to the hunt and the harshness of the cold months.

Together, the figures of the Four Seasons not only anchor the composition visually but also embody a deeper message of natural rhythm and divine governance. Their accompanying animals, drawn from both myth and the natural world, intensify the seasonal symbolism while reflecting the broader North African mosaic tradition, which skillfully weaves cosmic order with scenes of rural life and agricultural labor.

For Student Activities inspired by the La Chebba mosaic, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: American Journal of Archaeology, Jul. – Sep., 1903, Vol. 7, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1903), pp. 357-404 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America, and https://honorthegodsblog.wordpress.com/2015/02/25/triumph-of-neptune-and-the-four-seasons-from-la/, and https://www.romeartlover.it/Bardo.html