Aphrodisias, circa 410, white Phrygian (Dokimion) Marble, Height: 56 cm, Archaeological Museum of Chania, Greece

In the Archaeological Museum of Chania on the island of Crete, the Bust of a Lady offers a rare window into the shifting artistic and cultural values of the Late Roman and Early Christian period through the medium of female portraiture. During this era, women’s portraits began to diverge from classical Roman realism and overt displays of status, embracing a more stylized, introspective aesthetic aligned with emerging Christian ideals. Features such as large, contemplative eyes and serene expressions came to symbolize inner virtue and spiritual depth. While hairstyles and clothing still hinted at social rank, they also reflected increasing modesty, mirroring broader societal transformations.

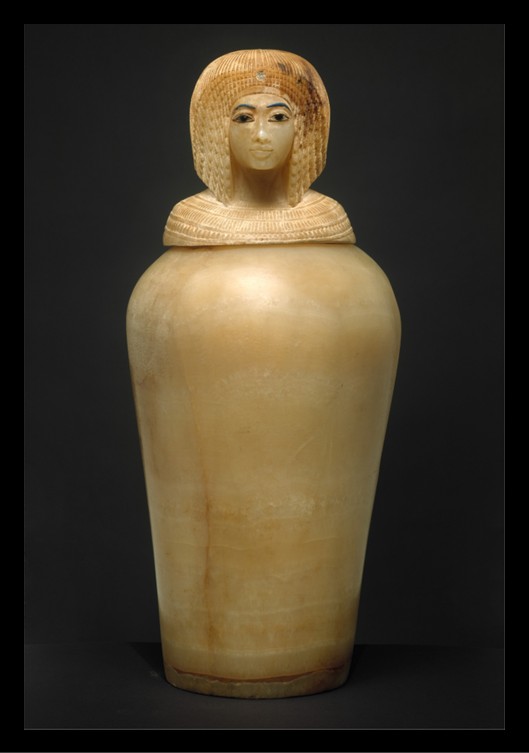

This particular bust depicts a woman of aristocratic beauty in the prime of her life, aged approximately 25 to 30. She is shown frontally, with her neck gently turned to the right, lending the portrait a poised and lifelike presence. Her oval face is framed by a tall forehead, almond-shaped eyes once inlaid with rose-colored glass, small full lips, and a strong chin—features that convey both grace and inner fortitude. A decorative band of twenty-two stylized curls runs across her forehead and temples, while four braids crown her head, testifying to her refined appearance.

She is draped in a heavy himation falling in deep, classical folds over a lighter chiton, a detail that evokes the sculptural traditions of earlier periods and enhances the portrait’s intellectual elegance. Although her left shoulder is only partially modeled, the form suggests the bust was designed for a niche setting, likely within a private villa, where such an omission would remain unseen. The combination of fine craftsmanship, classical references, and material opulence speaks to both her high status and the enduring artistry of late Roman Crete.

Although initially dated between the 2nd and 4th centuries, recent scholarship proposes a more precise date in the early 5th century, during the reign of Theodosios II (c. 410 AD). This dating is based on strong stylistic parallels with imperial portraits of Valentinian II and Theodosios II, and the bust is thought to have originated in an Asia Minor workshop, likely Aphrodisias. If correct, this attribution provides rare evidence of continued cultural and artistic exchange between Crete and Constantinople following the catastrophic earthquake of 365 AD.

This striking portrait, crafted from fine-grained marble was unearthed in 1982 in Nea Chora, a neighborhood of modern Chania that once formed the western sector of ancient Kydonia. Found in unstratified fill, it lacks a secure archaeological context. Nonetheless, the area was continuously inhabited from the Roman to early Byzantine periods, and the sculpture’s discovery in a historically wealthy district known for luxurious homes supports the notion that it belonged to an elite and culturally vibrant community.

While Crete is most famously celebrated for its Bronze Age Minoan civilization, the island also enjoyed a remarkable cultural resurgence under Roman rule, a period that produced refined works of art like the Bust of a Lady in the Archaeological Museum of Chania. In a region often viewed through the lens of its ancient past, the portrait from Kydonia invites us to appreciate the island’s lesser-known legacy: a vibrant late antique society that continued to engage with the broader currents of imperial art, identity, and belief.

For a Student Activity inspired by the Bust of a Lady in the Archaeological Museum of Chania, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: Heaven & Earth, Edited by Anastasia Drandaki, Demetra Papanikola-Bakirtzi, Anastasia Tourta, Exhibition Catalogue, Athens 2013 https://www.academia.edu/3655015/Heaven_and_Earth_Art_of_Byzantium_from_Greek_Collections_edited_by_Anastasia_Drandaki_Demetra_Papanikola_Bakirtzi_and_Anastasia_Tourta_Exh_cat_Athens_2013_238_9_275 Pages: 56-57 and https://amch.gr/collection/eikonistiki-protomi-astis-l-3176/