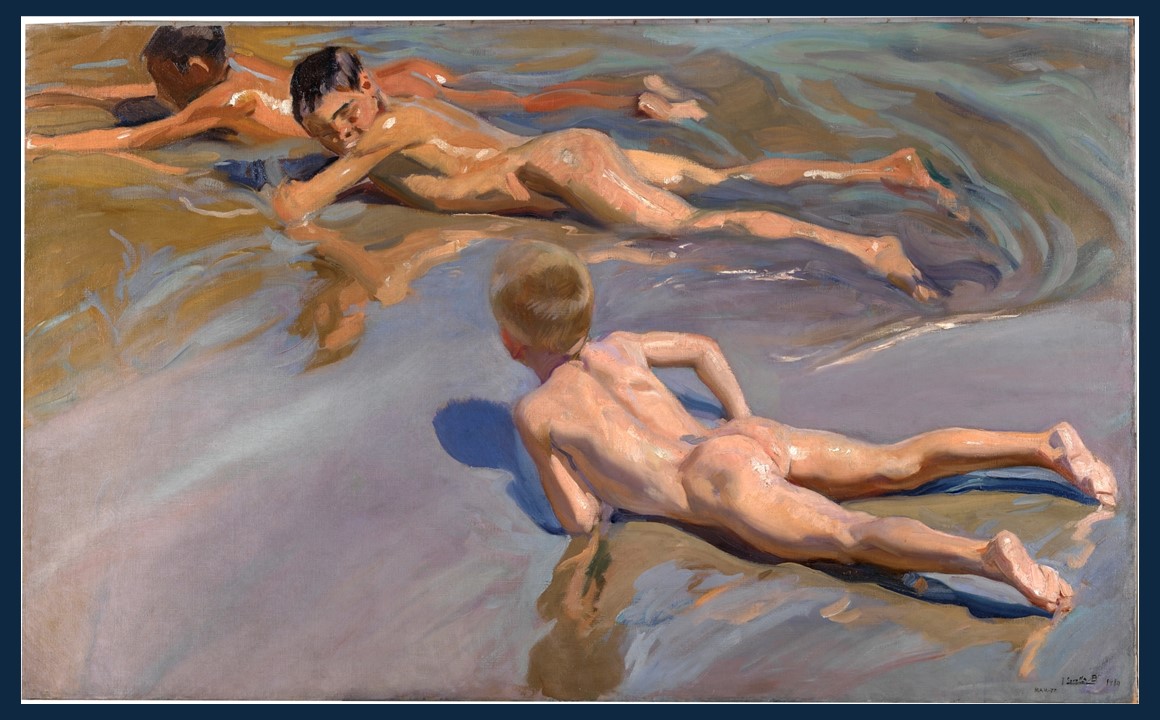

Saint in Prayer, 1888 – 1889, Oil on Canvas, 78×61 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/saint-in-prayer/992c8493-24c0-49ed-ac58-a4b690099b81

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida is a favourite Spanish artist of the late 19th early 20th century art scene. Saint in Prayer is a small gem of a painting, I find particularly intriguing. The Prado Museum description of its composition sets the tone masterfully… The small, frail figure of the young saint is placed before a sumptuous geometrically decorated golden backdrop. Sorolla must have used templates to produce some of the decoration, particularly the small squares on the surface of the wall and the gold circles on the dress, although in other cases he uses his brush to achieve the same effect. Particularly attractive is the combination of different circular shapes: the gold halo, the circle around a border with plant and animal motifs, the little circles on the dress. All are inspired by decorative patterns typical of the High Middle Ages. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/saint-in-prayer/992c8493-24c0-49ed-ac58-a4b690099b81

Born in Valencia in 1863, Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida showed an early talent for art, which led him to train at the Academy of San Carlos in his hometown. After completing his studies, he moved to Madrid, where he spent countless hours at the Museo del Prado, studying the works of great Spanish masters like Velázquez and El Greco. In 1885, a scholarship allowed him to study in Rome, deepening his exposure to classical art. He later spent time in Paris, where he encountered the emerging Impressionist movement, which influenced his focus on natural light and color. These experiences, combined with his Mediterranean roots, shaped his signature style, marked by vibrant depictions of sun-drenched beaches and lively scenes from everyday life.

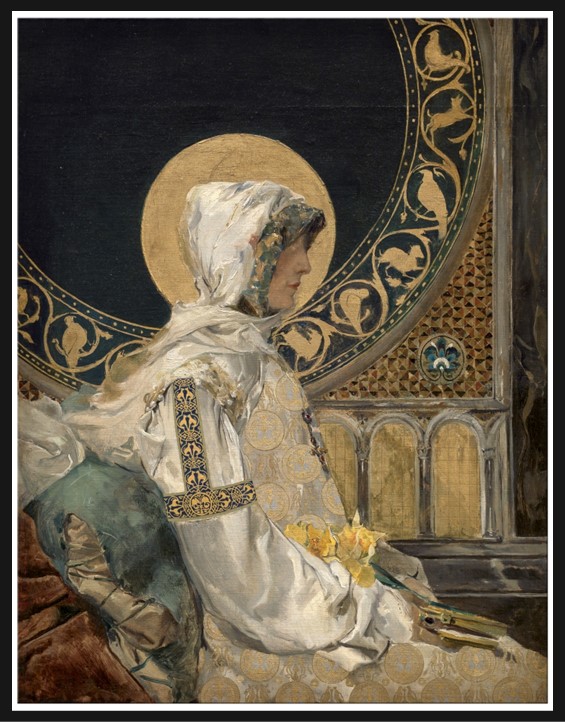

Throughout his life, Sorolla explored a wide range of subjects, from portraits and landscapes to social themes, yet his hallmark was the interplay of natural light, and his ability to capture the luminosity of the Spanish coast as exemplified in his painting Boys on the Beach (Tacher Curator BLOG POST of July 26, 2024). Marked by success in international exhibitions, gaining recognition for his vivid, sunlit canvases and his vibrant brushwork, Sorolla became one of Spain’s most celebrated artists. https://www.teachercurator.com/art/boys-on-the-beach-by-joaquin-sorolla-y-bastida/

On the 8th of September 1888, in Valencia, Sorolla married Clotilde García del Castillo, his confidant, traveling companion, bookkeeper (or in his words, “my Treasury Minister”), and muse. Shortly after, along with his friend Juan Antonio’s sister, the couple travelled to Italy and spent a period in Assisi where Sorolla began to paint “genre scenes” to earn a living. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437706

Señora de Sorolla in Black, 1906, Oil on Canvas, 186.7 x 118.7 cm, the MET, NY, USA https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Se%C3%B1ora_de_Sorolla_

(Clotilde_Garc%C3%ADa_del_Castillo,_1865%E2%80%931929)_in_Black_MET_DP168810.jpg

Sorolla painting ‘Clotilde in a Black Dress’, 1905. Photograph by Christian Franzen © Museo Sorolla, Madrid, Spain

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/past/sorolla/what-you-need-to-know-about-sorolla

This period was pivotal in shaping Sorolla’s artistic development, as it introduced him to the Italian Renaissance masters. During this time, he concentrated on religious subjects, one notable example being Saint in Prayer (1889), now housed in the Museo del Prado. The painting reflects Sorolla’s sensitivity to spiritual themes, employing a soft, glowing light that reveals his growing ability to capture mood through illumination—a hallmark of his later, more renowned works. Treasured by Sorolla and his wife, the piece held a special place in their home. In his 1906 portrait Señora de Sorolla in Black, the painting features prominently in the background, framing Clotilde’s face. Sorolla’s time in Assisi refined his technical skills and deepened his fascination with the interplay of light, setting the foundation for his future artistic achievements.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of the artists oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.cultura.gob.es/dam/jcr:9fa09fae-ac06-454d-b8ad-8c904954f240/biografia-eng-origenes.pdf