. The 14th of July is the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille, a major event of the French Revolution, and the most important French Fête Nationale! Let’s celebrate this important historical event with a story… that of The Treasure of Childeric I, its beautiful Bee-Shaped Jewels and… Napoleon!

The Treasure of Childeric I, discovered on May 27th, 1653, in Tournai, Belgium, by Adrien Quinquin, a mason working on the reconstruction of the Church of Saint-Brice, is an extraordinary archaeological find that offers a unique glimpse into the early medieval period of European history. Attributed to Childeric I, a prominent king of the Salian Franks and father of Clovis I, the founder of the Merovingian dynasty, the hoard included a remarkable array of artefacts, such as jewelry, coins, and ceremonial weapons, reflecting the wealth and craftsmanship of the time.

Childeric I reigned during a pivotal era marked by the transition from Roman rule to establishing Frankish kingdoms. Therefore, his treasure highlights the personal wealth and power of a Frankish king and serves as a cultural bridge between the late Roman Empire and the early medieval Frankish state. Each item within the treasure provides invaluable insights into the art, culture, and political dynamics of the 5th century.

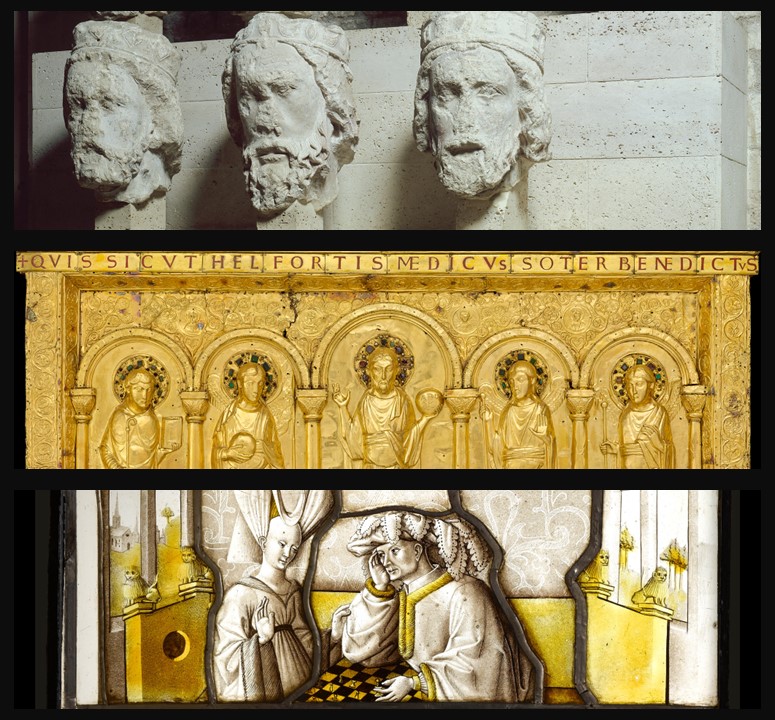

The discovery of Childeric’s treasure was a landmark event in the field of archaeology and has since played a crucial role in shaping our understanding of Merovingian art and society. The Treasure included a variety of fascinating items: a throwing axe, a spear, a long sword known as a spatha, and a short scramasax, both adorned with gold and garnet cloisonné. There was also a solid gold torc bracelet, part of an iron horseshoe with nails still intact, and belt and shoe buckles as well as horse harness fittings, all elaborately decorated with cloisonné gold and garnets. Additionally, the collection contained a leather purse with over a hundred gold and silver coins, the latest of which featured the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (474-491 A.D.). Among the treasures were also a gold bull’s head with a solar disc on its forehead, a crystal ball, and a gold signet ring.

Among the most notable items were the gold and enamel bees, over 300 of them, which were likely used as decorations for Childeric’s cloak or other regalia. These bees were later adopted by Napoleon Bonaparte, who, preparing for his coronation as Emperor of the French, sought a link to ancient French royalty. He deliberately avoided the still-despised Bourbon fleur-de-lys symbol, espousing Childeric’s heraldic bees as his emblem. Consequently, Napoleon’s coronation robe was embroidered with 300 gold bees, establishing them as the symbol of the new French Empire, and associating himself with the continuity and authority of the ancient Frankish kings. The bees thus became emblematic of the Napoleonic regime, symbolizing immortality and resurrection. In modern times, the bee has also contributed to the commemoration of the 14th of July national holiday, symbolizing the unity and enduring spirit of the French nation.

The Treasure’s discovery

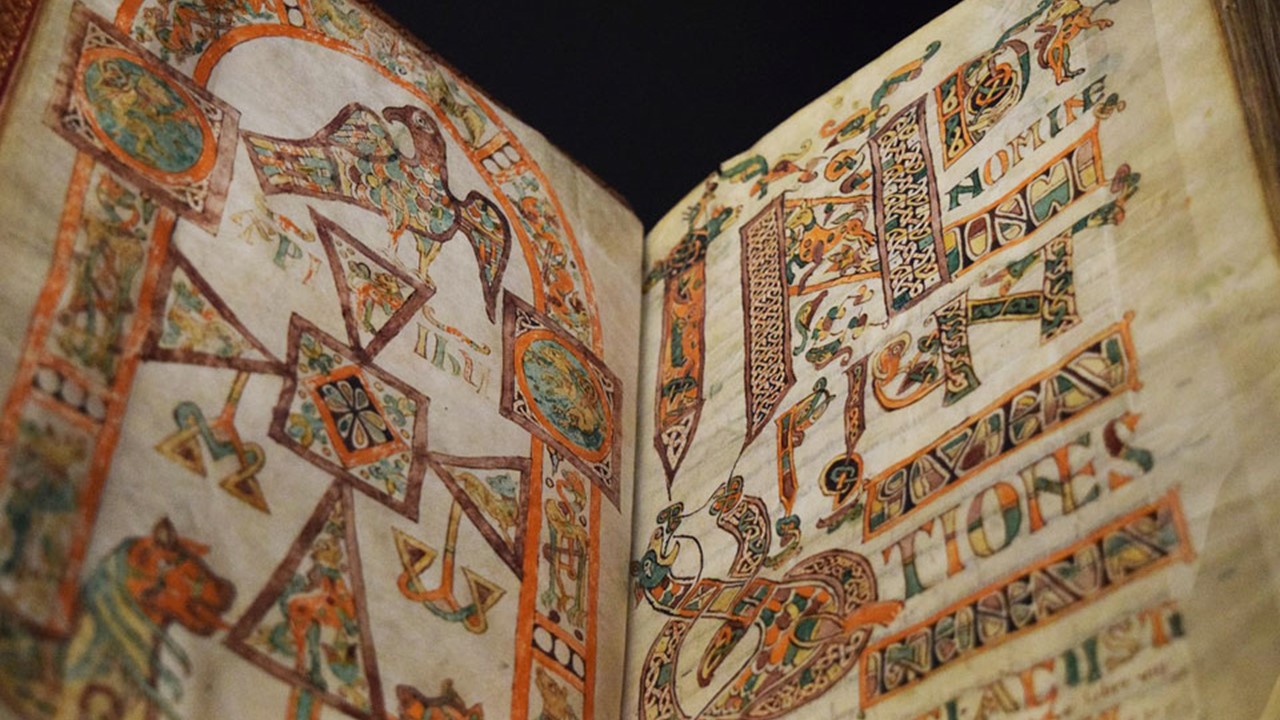

When Childeric’s treasure was discovered in 1653 in Tournai, then part of the Spanish Netherlands, it was sent to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. Recognizing its importance, the Archduke commissioned his physician, Jean-Jacques Chifflet, to document the artefacts meticulously. Chifflet’s detailed study, including precise engravings, was published in 1655 as “Anastasis Childerici I,” marking the first scientific archaeological publication. Although Chifflet made some errors in his analysis, his work laid the groundwork for modern archaeological documentation, preserving invaluable information about the Merovingian dynasty. Archduke Leopold brought Childeric’s treasure to Vienna in 1656 and, upon his death in 1662, bequeathed it to his nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, who gifted the treasure to King Louis XIV. Louis, unimpressed by the 5th-century artefacts, stored them in the Louvre’s Cabinet of Medals. After the French Revolution, the treasure became part of the Cabinet of Medals at the Imperial Library, later known as the National Library of France.

On the night of November 5th, 1831, thieves broke into the Cabinet of Medals at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, stealing over 2,000 gold objects, including Childeric’s treasure. The exact sequence of events is unclear due to record losses during the Paris Commune of 1871. The theft was a major scandal, prompting the reappointment of Eugène-François Vidocq, founder of the Sûreté, to lead the investigation and recover the treasure. With Vidocq in charge (Vidoq was a former criminal and convict turned policeman, believed to be Victor Hugo’s inspiration for Javert and Valjean of Les Misérables) a portion of the stolen treasure was retrieved from the Seine River where it was hidden in leather bags. Unfortunately, the treasure’s theft led to a dramatic loss of French cultural heritage, as only a portion of the treasure was recovered with many pieces lost forever. Today, the Treasure of Childeric I remains a testament to the historical significance and enduring legacy of the early Frankish rulers.

For a PowerPoint on The Treasure of Childeric I, please… Check HERE!