https://www.penn.museum/collections/object_images.php?irn=293415#image2 and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enheduanna

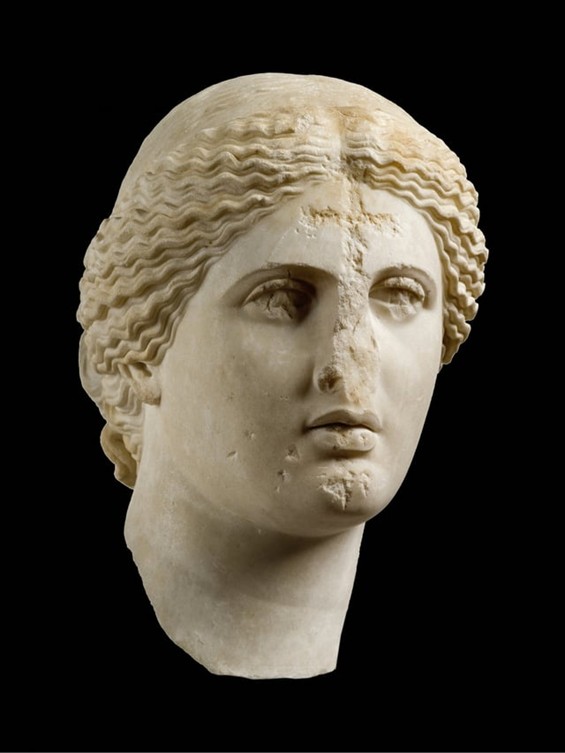

On the eve of International Women’s Day, this post turns to Enheduanna the first named author in history, a princess and high priestess whose voice still resonates across four millennia. Daughter of Sargon of Akkad and high priestess of the moon god Nanna at Ur, Enheduanna shaped religious thought through both word and image, uniting political authority, ritual practice, and poetic devotion. An alabaster disk dedicated in her sacred precinct preserves not only her name but also her likeness, depicting her presiding over a solemn rite as her gaze lifts from the mortal realm toward the divine presence of Inanna. Fragmentary yet powerful, this object stands as a rare testament to a woman who claimed authorship, spiritual authority, and enduring legacy in the ancient world.

Who was Enheduanna, and how did she choose to be remembered? What does it mean that the earliest named author in human history is known not only through texts, but also through an image that stages ritual authority with deliberate clarity? And how can a fragmentary disk, copied centuries after her lifetime, still speak so eloquently about power, devotion, and presence? These questions shape our encounter with Enheduanna today, inviting us to look closely at how identity was constructed and preserved in the sacred spaces of ancient Mesopotamia.

Who Was Enheduanna, the First Named Author in History? Enheduanna lived in the twenty-third century BC, when political unification and religious practice were inseparable, and as daughter of Sargon of Akkad she was appointed high priestess of the moon god Nanna at Ur to lead the city’s religious community and mediate between Akkadian imperial authority and long-established Sumerian cult traditions. Her name matters because she did not remain an anonymous officeholder: through first-person hymns to Inanna and an inscribed alabaster disk whose cuneiform text was preserved and recopied centuries later, Enheduanna asserted authorship and ensured that her identity was not incidental but deliberately transmitted memory, in this case, functioning as an act of cultural continuity.

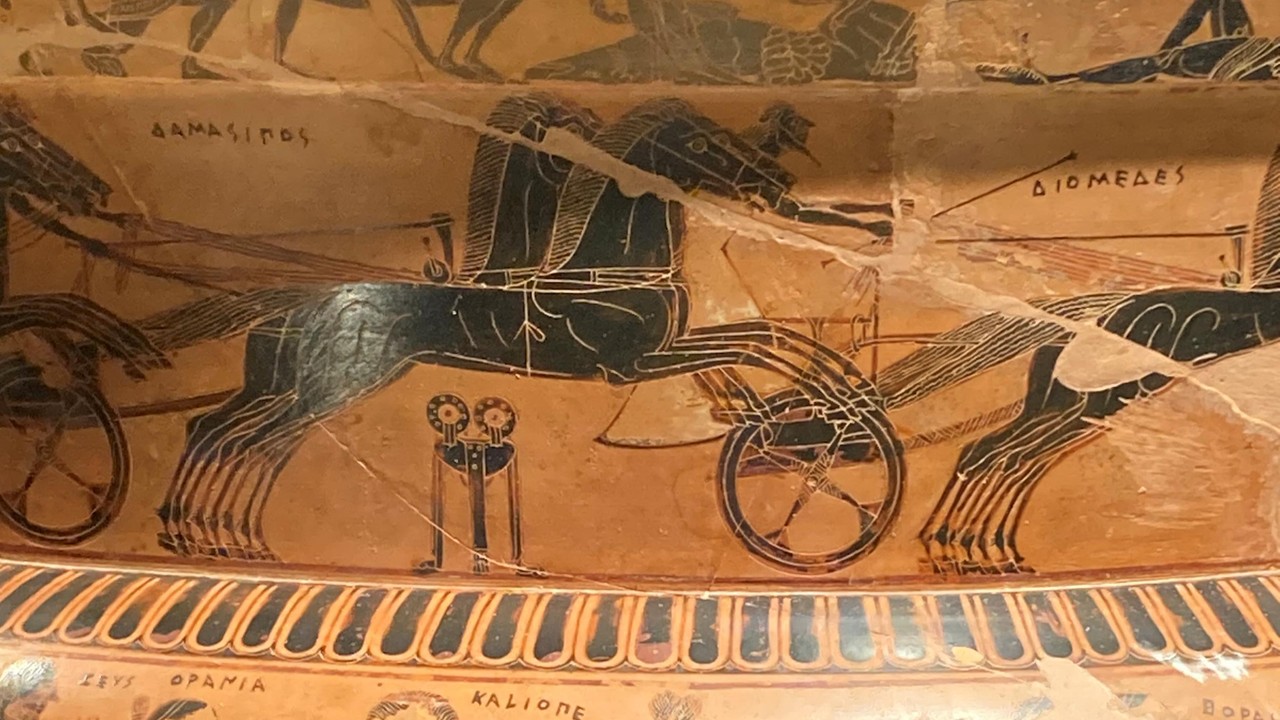

What does the Disk show us about Power and Presence? Carved in alabaster, the disk presents Enheduanna at the center of a ritual scene within an open-air sacred precinct. She is depicted slightly larger than the priests who accompany her, a visual strategy that signals hierarchy without excess. Her posture is composed, her presence commanding but restrained. The multistory structure at left situates the ritual within architectural space, reinforcing the institutional framework of her authority. Power here is not enacted through force or spectacle, but through sanctioned participation in sacred rites.

How does ritual become image? The scene unfolds with careful economy. Two priests follow Enheduanna, carrying ritual paraphernalia, while the figure before her pours a libation over an altar. Enheduanna’s raised hand authorizes the act, transforming gesture into command. Her tiered, flounced garment and circlet headdress—elements that would become canonical for high priestesses—mark her role with visual precision. The disk does not narrate ritual; it distills it, translating repeated ceremonial practice into a permanent, legible image.

Why does Enheduanna look upward? Perhaps the most arresting element of the disk is Enheduanna’s gaze. Her well-sculpted face turns upward, bridging the space between the human and the divine. This upward orientation is not expressive in a modern emotional sense, but symbolic: it situates her as intermediary, one who mediates between earthly ritual and the numinous presence of Inanna. The image thus encodes theology as posture, belief as direction of sight.

Why does Enheduanna still Matters Today? Enheduanna’s legacy is not only one of authorship, but of resilience under political rupture. Toward the end of the reign of Narām-Sîn, the Akkadian Empire was shaken by widespread rebellion. In Ur, a ruler named Lugal-Ane seized power and invoked the authority of the moon god Nanna to legitimize his rule. As high priestess and representative of the Sargonid dynasty, Enheduanna was called upon to sanction this claim. She refused.

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20221025-enheduanna-the-worlds-first-named-author

Her refusal had consequences. Enheduanna was stripped of her office and expelled from Ur, forced into exile, likely in the city of Ĝirsu. It is from this position of displacement that she composed Nin me šara (The Exaltation of Inanna), a hymn that is both a devotional appeal and a political act. Speaking directly to the goddess, Enheduanna narrates injustice, loss, and restoration, transforming personal suffering into ritual speech intended to move the divine realm itself.

When Narām-Sîn eventually suppressed the rebellion and restored Akkadian authority, Enheduanna appears to have returned to her post. Her survival, political, ritual, and textual, is remarkable. She emerges not as a passive figure preserved by history, but as an active agent who used language, ritual authority, and divine appeal to endure and reassert her position.

https://ajaonline.org/museum-review/4785/

This dimension of Enheduanna’s life sharpens her relevance today. She matters not only because she was the first named author, but because she wrote in crisis, from exile, and against erasure, consciously shaping how her words would endure. In Nin me šara, she frames her hymn as an act of creation and transmission: “I have given birth, / Oh exalted lady, (to this song) for you. / That which I recited to you at (mid)night / May the singer repeat it to you at noon!” Her voice endures because it was forged in instability and entrusted to repetition, preserved not by chance, but because it was meant to be carried forward long after the immediate conflict had passed.

On this International Women’s Day, we honor Enheduanna as a reminder that women’s voices, like hers, forged in authority, creativity, and resilience, have shaped history and continue to inspire across millennia.

For a PowerPoint Presentation titled Mesopotamia’s Women Who Wrote History, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: a BBC Article https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20221025-enheduanna-the-worlds-first-named-author, from Penn Museum Expedition Magazine https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/goddesses-mothers-rulers/ and from the Morgan Library https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/online/she-who-wrote