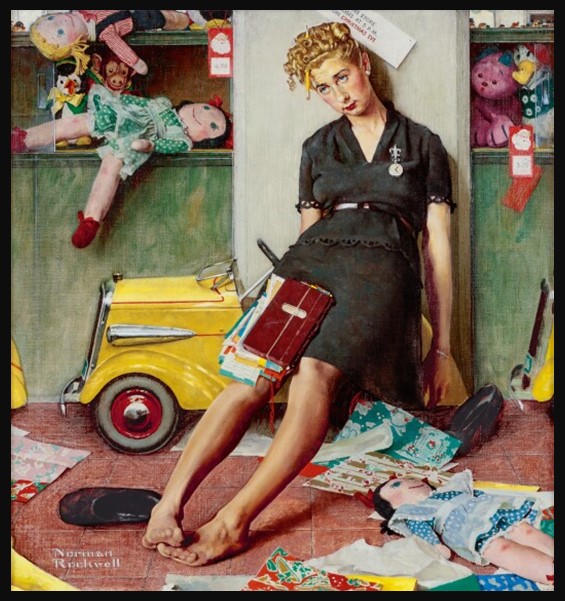

Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve, 1947, Oil on Canvas, 77.2×71.8 cm, Private Collection

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2018/american-art-n09939/lot.19.html?locale=en

Under the soft glow of a dim shop light, Norman Rockwell captures a rare moment of quiet humanity in Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve. Departing from his more festive and bustling holiday scenes, Rockwell instead lingers in stillness, an ode to the unseen fatigue and quiet dignity behind the season’s glittering façade. The weary young woman, slumped in exhaustion yet imbued with humble strength, invites viewers to pause and reflect on the hidden cost of holiday cheer. Through Rockwell’s tender realism, the painting becomes not merely a portrait of fatigue but a meditation on empathy, perseverance, and the fragile beauty found in life’s most ordinary moments.

Norman Rockwell and Postwar America

Painted in 1947, Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve emerged during a period when Norman Rockwell’s art both comforted and gently challenged postwar America. Known for his warm, narrative depictions of American life, Rockwell was celebrated for scenes of family gatherings, civic pride, and small-town cheer. Yet beneath his accessible style lay a deep interest in the quiet realities that accompany those ideals.

The Saturday Evening Post Cover of 1947

This painting first appeared on the December 27, 1947, cover, of the The Saturday Evening Post. Rockwell’s image, however, defied the glossy optimism often associated with holiday imagery. Rather than portraying festive joy, he chose to honor the fatigue of those who made it possible, the clerks, shop assistants, and unseen workers who sustained the season’s magic. In doing so, Rockwell bridged the gap between commercial illustration and social observation, creating a moment of artful empathy within a mass-market context.

Visual Storytelling and Quiet Exhaustion

In this work, Rockwell captures the quiet exhaustion of a department store employee after the frenzy of last-minute Christmas shopping. The young woman slumps against the wall, her shoes kicked off and forgotten among scraps of wrapping paper and discarded toys. Behind her, a crooked sign announces the store’s closing at 5:00 p.m., while her watch reads 5:05 — a subtle detail that deepens the sense of fatigue. A soft amber light pools around her, isolating her from the dim surroundings and transforming a moment of weariness into one of tender humanity. The forlorn dolls that echo her pose yet wear painted smiles emphasize Rockwell’s gift for visual storytelling, revealing the bittersweet undercurrent of the holiday season.

Every surface carries evidence of touch: the texture of fabric, the gleam of glass, the faint sheen of perspiration on her brow. Yet the tone remains tender rather than pitiful. Rockwell paints her not as a figure of complaint, but of endurance, a study in quiet perseverance and human worth. The restrained palette and focused lighting draw the viewer inward, evoking a sense of stillness rarely found in his more bustling compositions.

Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve reveals Rockwell’s capacity to dignify the ordinary. By choosing this moment of rest, he acknowledges the hidden labor behind holiday abundance. The young woman’s weariness speaks not only to her physical fatigue but to a universal truth: that celebration often depends on invisible work.

In the context of 1940s America, a nation balancing prosperity with postwar fatigue, this image would have resonated deeply. It aligned with Rockwell’s broader humanist vision, one that sought to find beauty in effort, humor in humility, and grace in imperfection. Today, that same sensibility feels remarkably contemporary, echoing ongoing conversations about emotional labor and the value of unseen work.

Why Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve Still Matters

More than seventy years later, Rockwell’s salesgirl continues to move viewers not through spectacle, but through empathy. She reminds us that art can elevate even the most fleeting moments of human vulnerability into symbols of shared experience. In an era when holiday imagery still tends to idealize perfection, Rockwell’s painting invites a different kind of reflection, one grounded in compassion and authenticity.

Ultimately, Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve stands among Rockwell’s most introspective works. Through his careful attention to gesture, light, and narrative restraint, he transforms a common scene into an enduring meditation on care, work, and quiet resilience. The painting whispers rather than declares, yet in that whisper lies Rockwell’s deepest gift: a reminder that every moment of exhaustion carries its own quiet form of grace.

Rockwell’s art endures because it recognizes the humanity in all of us, the moments when we pause, rest, and simply are. In Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve, that recognition becomes both personal and universal. It is not merely a scene of fatigue, but a portrait of empathy, a testament to the dignity of effort and the quiet beauty found at the close of a long day.

For a student activity on Norman Rockwell’s painting Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve, please… Click HERE!

Bibliography: Sotheby’s catalogue entry for Tired Salesgirl on Christmas Eve

Rockwell’s sensitivity to everyday labor can also be seen in Freedom from Want and Happy Birthday, Miss Jones, both discussed elsewhere on Teacher Curator: https://www.teachercurator.com/20th-century-art/freedom-from-want-by-norman-rockwell/ and https://www.teachercurator.com/student-activities/happy-birthday-miss-jones-by-norman-rockwell/?fbclid=IwY2xjawN2gpVleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFacmdpSHp2SEZOb3lLZWFaAR6o_s1cbQ-iJ3seOTei9EK-NSGSKJwa-goSlQRlZ0OVo3e56Vs6jHCgU9nABw_aem_D0lNpQ7pRe6EhsgcZxX9CA&brid=zUGuYS_L6hPdqRsBBliuag