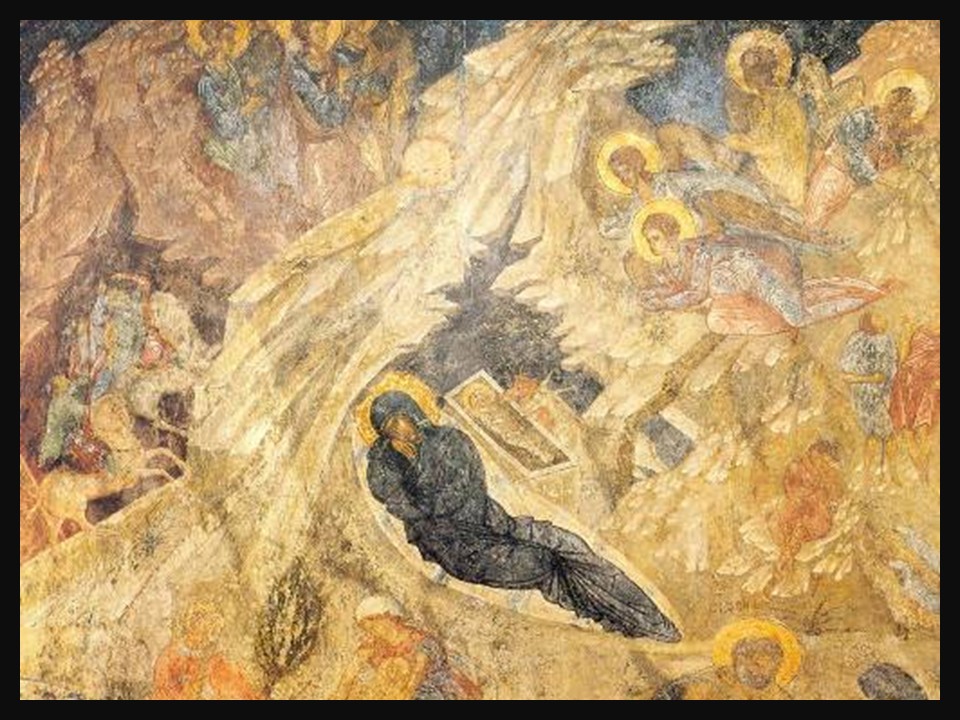

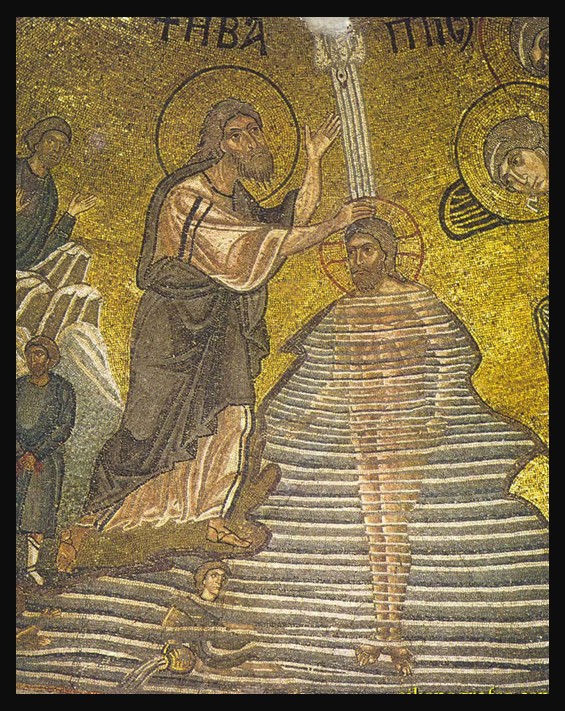

Every year on January 7, the Orthodox Church celebrates the Feast of Saint John the Forerunner, the prophet who prepared the way for Christ and baptized Him in the Jordan River. On the island of Chios, this commemoration finds a particularly resonant setting in Nea Moni, the 11th-century monastic foundation distinguished for its architectural integrity and exceptional mosaic decoration. In the Katholiko, the mosaic of the Baptism of Christ stands out for its refined handling of the sacred narrative: the descending waters of the Jordan, the presence of attendant angels, and the hieratic figure of Christ are rendered in luminous gold and saturated blues typical of Middle Byzantine aesthetics. The composition not only conveys a key episode of Christian theology but also reflects the spiritual and artistic ambitions of the monastery’s patrons and craftsmen.

Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, 2025

Perched on the slopes of Mount Provateftis, Nea Moni’s founding is closely tied to a local legend involving three hermits who discovered a miraculous icon of the Virgin beneath a myrtle tree. Each attempt to relocate the icon resulted in its return to the original site, a phenomenon interpreted as divine intervention. Reports of the miracle reached Empress Zoe and the future Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos, whose visions of the Virgin prompted them to grant imperial patronage between 1049 and 1055. Their involvement enabled the construction of a monumental complex that united imperial ideology, theological symbolism, and monastic devotion. Over subsequent centuries, Nea Moni flourished as a center of worship, pilgrimage, and artistic production, even as it later endured phases of decline, particularly under Ottoman rule.

Middle Byzantine Mosaics and the Macedonian Renaissance

The monastery’s historical and artistic significance is encapsulated in its mid-11th-century mosaics, among the finest surviving ensembles of Middle Byzantine art. Although the dome mosaic of the Katholiko has perished, likely once depicting Christ Pantocrator with attendant angelic powers, substantial portions of the original decoration survive. In the pendentives, mosaics of the Cherubim and Seraphim remain, along with two Evangelists, John (despite heavy damage) and Mark. In the apse, the Virgin Platytera is preserved headless. Below these, the octagonal wall surfaces retain important scenes from the Dodekaorton, continuing also into the narthex. The Baptism, Crucifixion, and Anastasis form what is often regarded as the ensemble’s most accomplished triad, characterized by subtle modeling, expressive gestures, and a refined chromatic palette, while additional scenes include the Transfiguration and Deposition. The narthex once displayed a now-lost mosaic of the Virgin Orans in its small dome, surrounded by full-length military saints set within arched frames, and its vaults presented six Christological compositions, some of which survive only fragmentarily.

https://www.pallasweb.com/deesis/byzantine-mosaics-of-nea-moni-on-chios.html

These works collectively reveal multiple stylistic currents of the late Macedonian period: classicizing figures with volumetric bodies and balanced stances appear alongside more linear, expressive compositions that anticipate later developments in Byzantine art. The extensive use of gold ground and deliberate reduction of spatial depth contribute to an ethereal, otherworldly atmosphere, while sophisticated optical adjustments on curved surfaces demonstrate the technical skill and theoretical awareness of artists likely trained in the imperial workshops of Constantinople.

When compared with contemporaneous mosaic cycles at Osios Loukas and Daphni on the Greek mainland, Nea Moni demonstrates both adherence to shared Byzantine conventions and distinctive regional features. All three complexes employ similar hierarchical structures, with Christ Pantocrator originally presiding from the dome and a surrounding ensemble of heavenly and apostolic figures reinforcing Middle Byzantine theological ideals. Yet while Osios Loukas and Daphni tend toward more monumental proportions and sculptural modeling, Nea Moni is marked by a lighter chromatic range, subtler facial expression, and delicate rendering of form. These distinctions highlight the diversity of artistic production across the Byzantine world and underscore Nea Moni’s significance as a particularly refined example of 11th-century Aegean mosaic art. Together, these monuments attest to a period of exceptional creativity in Middle Byzantine ecclesiastical decoration and affirm the enduring cultural and spiritual importance of Nea Moni.

For a PowerPoint Presentation, inspired by the ‘Feast Day of Saint John the Forerunner’ Blog Post and the Mosaics in the Nea Mony, in Chios, please… Click HERE!

Bibliography: https://smarthistory.org/mosaics-and-microcosm/ and from’My World of Byzantium’ https://www.pallasweb.com/deesis/byzantine-mosaics-of-nea-moni-on-chios.html