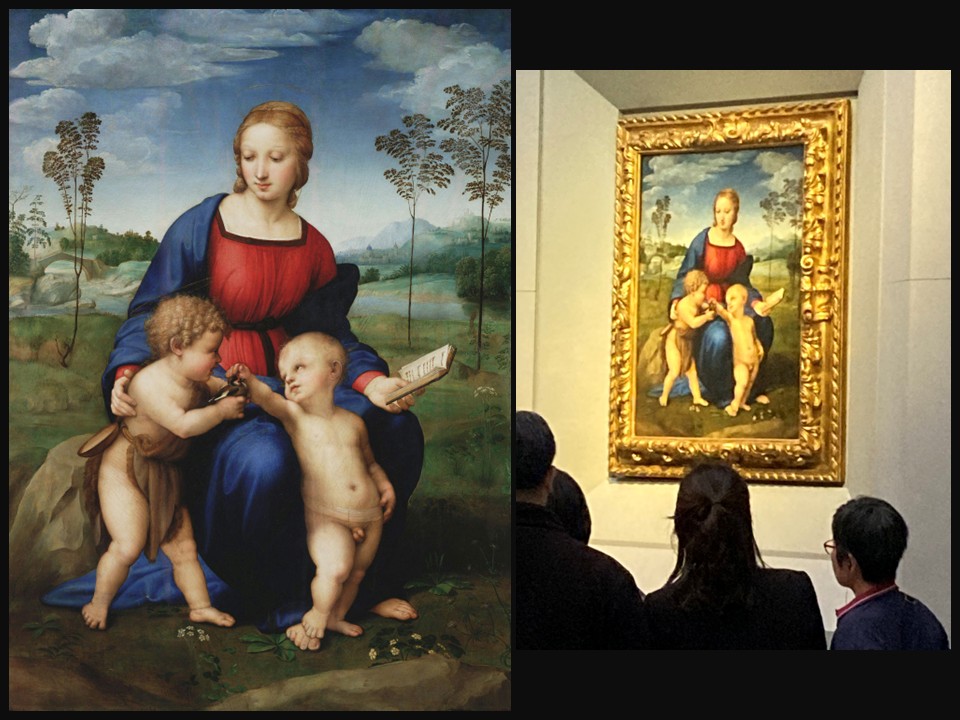

Apollo and Pan, or The Judgment of Tmolus, Date unknown, Oil on Panel, originally a harpsichord lid painting cut into a rectangle, 87.5 × 154 cm, Private Collection

https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/collections-provenant-des-familles-cosse-brissac-dormesson-la-bedoyere/jean-francois-de-troy-paris-1679-1752-rome-65/273871?ldp_breadcrumb=back

Jean-François de Troy and the Myth of Apollo and Pan presents a refined visual interpretation of one of classical antiquity’s most evocative musical contests, drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In this painting, de Troy depicts the moment of judgment presided over by Mount Tmolus, as Apollo’s harmonious lyre is weighed against Pan’s rustic pipes—a confrontation that embodies the enduring opposition between cultivated order and untamed nature. Executed with the elegance and narrative clarity characteristic of French Rococo classicism, the work reveals de Troy’s sophisticated engagement with mythological subject matter, not merely as decorative allegory but as a vehicle for exploring hierarchy, taste, and aesthetic authority. Through careful orchestration of gesture, expression, and setting, the artist transforms a poetic episode into a scene of moral and artistic arbitration, inviting the viewer to consider both the power of divine judgment and the cultural values embedded within myth itself.

Iconography and Style

De Troy’s iconographic choices closely follow Ovid’s narrative while simultaneously adapting it to the visual and intellectual tastes of early eighteenth-century France. Apollo is presented with idealized grace, his poised stance and luminous flesh underscoring his association with reason, harmony, and artistic supremacy, while Pan’s earthbound physicality and animated gestures emphasize his alignment with instinct and the pastoral realm. The presence of Tmolus, elevated yet contemplative, reinforces the painting’s central theme of judgment, his gesture serving as a visual fulcrum between the two competing musical ideals. Set within a softly rendered Arcadian landscape, the scene is infused with the delicate color palette, fluid contours, and theatrical compositional balance that distinguish de Troy’s mature style. These Rococo refinements do not diminish the moral gravity of the myth; rather, they recast it as an elegant meditation on taste and authority, reflecting contemporary debates within the French Academy about artistic hierarchy, decorum, and the civilizing power of the arts.

About Jean-François de Troy

Jean-François de Troy (1679–1752) was born in Paris into an artistic family, the son of the painter François de Troy, from whom he received his earliest training. He entered the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in 1708 and soon established himself as a versatile painter of history, portraiture, and decorative scenes. In 1714 he was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome, which enabled him to study in Italy, where he immersed himself in classical antiquity and the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters. This Italian sojourn proved formative, sharpening his narrative sensibility and compositional clarity. Upon his return to France, de Troy enjoyed significant success within aristocratic and courtly circles, culminating in his appointment as director of the French Academy in Rome in 1738, a position he held until his death and through which he exerted considerable influence on the next generation of French artists.

De Troy’s oeuvre is distinguished by its synthesis of classical erudition and Rococo refinement, marked by elegant figuration, fluid draftsmanship, and a keen sensitivity to gesture and expression. While firmly grounded in the academic tradition of history painting, his works often soften heroic grandeur through graceful movement, sensual surfaces, and an intimate engagement with narrative detail. He demonstrated a particular talent for translating literary and mythological sources into visually coherent and emotionally legible scenes, balancing intellectual rigor with decorative appeal. Across religious, mythological, and genre subjects alike, de Troy consistently privileges clarity of storytelling and refined theatricality, qualities that align his work with the broader cultural ideals of early eighteenth-century France. His paintings thus occupy a pivotal position between the authority of classical tradition and the emerging taste for elegance, pleasure, and psychological nuance that defines the Rococo aesthetic.

Apollo and Pan in Context

Seen within the broader scope of Jean-François de Troy’s career, Apollo and Pan exemplifies his ability to reconcile learned mythological subject matter with the refined sensibilities of his age. The painting encapsulates his commitment to narrative clarity, intellectual elegance, and visual harmony, qualities that define his most accomplished history paintings. By presenting the Judgment of Tmolus not as a moment of dramatic conflict but as a poised act of aesthetic discernment, de Troy aligns the ancient myth with contemporary ideals of taste and artistic authority. In doing so, he affirms the enduring relevance of classical narratives while subtly asserting the values of academic tradition in an era increasingly drawn to grace and pleasure. Apollo and Pan thus stands as both a testament to de Troy’s mastery and a nuanced reflection on the cultural role of art itself.

The scene depicted in Jean-François de Troy’s Apollo and Pan is drawn from the myth recounted by Ovid in Book 11 of his Metamorphoses (lines 146–171), where Pan and Apollo compete in a musical contest before Mount Tmolus. You can read the full episode in an accessible English translation online: 🔗 Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 11 (Pan and Apollo) – https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph11.htm#485520964

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Jean-François de Troy’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: Christie’s Lot Essay: https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/collections-provenant-des-familles-cosse-brissac-dormesson-la-bedoyere/jean-francois-de-troy-paris-1679-1752-rome-65/273871?ldp_breadcrumb=back and WebMuseum presentation: https://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/troy/?utm_source=chatgpt.com