Infinity Mirrored Room – A Wish for Human Happiness Calling from Beyond the Universe, 2020, Mirrors, wood, LED lighting system, metal and acrylic panel

293.7 × 417 × 417 cm, Guggenheim, Bilbao, Spain – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, Spring 2024

As the year draws to a close and we turn our thoughts toward renewal, Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrored Room – A Wish for Human Happiness Calling from Beyond the Universe feels especially resonant. Inside this glowing chamber of reflections and color, time seems to dissolve, we’re surrounded by an endless constellation of lights that echo both our dreams and our fragility. Kusama, now in her nineties, transforms her lifelong visions into a universal wish for happiness and connection. Standing within her mirrored infinity, we are invited to let go of boundaries and imagine a world where light, like hope, multiplies without end.

Rather than simply offering spectacle, Kusama’s mirrored room opens a path inward, toward reflection, empathy, and the dissolution of the self. The rhythmic interplay of light and shadow evokes the bodily act of breathing, creating an immersive environment that mirrors both the fragility and persistence of life. Within this spatial choreography, viewers become part of the artwork itself, their reflections multiplying until individuality gives way to a collective presence. Kusama transforms the visual language of repetition, often associated with compulsion or anxiety, into a meditative gesture that suggests endurance, healing, and transcendence.

Her sustained engagement with repetition and reflection emerged from deeply personal experiences of hallucination, which she has long described as both tormenting and visionary. By externalizing these internal visions, Kusama converts psychological intensity into aesthetic experience. The Infinity Mirror Rooms thus function as both self-portrait and cosmology: spaces where personal trauma expands into universal form. The viewer’s image, endlessly reproduced and dissolved, echoes Kusama’s own quest to reconcile selfhood with infinity. In this mirrored glow, individuality is neither lost nor affirmed but transformed into a shared awareness of impermanence and renewal.

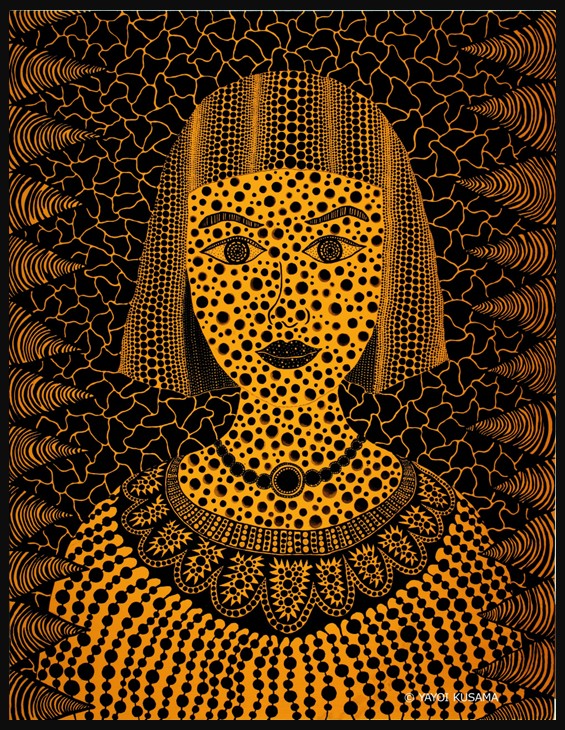

Self-Portrait, 2015, Acrylic on Canvas, 145.5×112 cm, Collection of Amoli Foundation

https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/exhibition/self-portrait

From Personal Vision to Universal Experience

Yayoi Kusama, born in 1929 in Matsumoto, Japan, is a pioneering contemporary artist whose work spans painting, sculpture, performance, and installation. From an early age, she experienced vivid hallucinations and obsessive visions, often of patterns and repetitive dots, which deeply influenced her artistic language. These lifelong obsessions with infinity and self-obliteration culminated in her immersive Infinity Mirror Rooms, first created in the 1960s. By surrounding viewers with mirrored walls, glowing lights, and endless reflections, these installations externalize Kusama’s internal experiences, creating a sense of boundlessness and allowing audiences to step into her unique perception of the universe, where the boundaries between self and environment dissolve.

As we approach the New Year, Kusama’s mirrored infinity becomes a gentle reminder of continuity and renewal. Each point of light suggests a possibility, each reflection a chance to see the world anew. Her wish for “human happiness” extends beyond the room, echoing outward — a constellation of hope for the year to come.

For a Student Activity inspired by Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms, please… Click HERE!

Bibliography: from the Guggenheim in Bilbao, Spain https://www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus/en/the-collection/works/infinity-mirrored-room-a-wish-for-human-happiness-calling-from-beyond-the-universe and the TATE Modern https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/yayoi-kusama-infinity-mirror-rooms and from the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, USA https://high.org/exhibition/yayoi-kusama-infinity-mirrors/