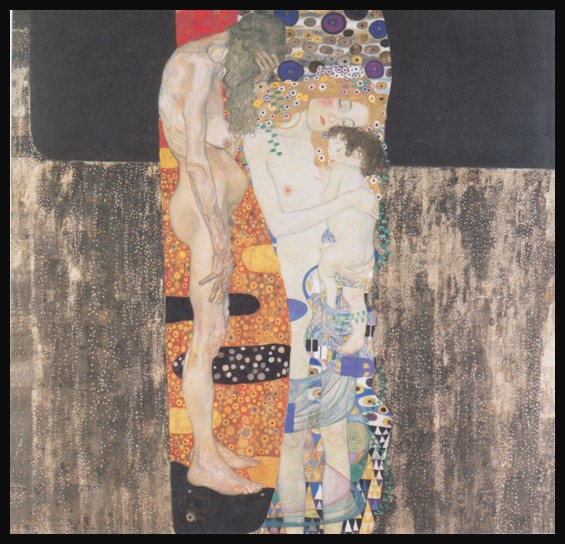

Pandora and Epimetheus, 1600 – 1610, Polychromed, Carved Wood, Height: 43 cm, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/pandora/86a6b73f-8ef3-4132-aa68-4648a27a4b6a

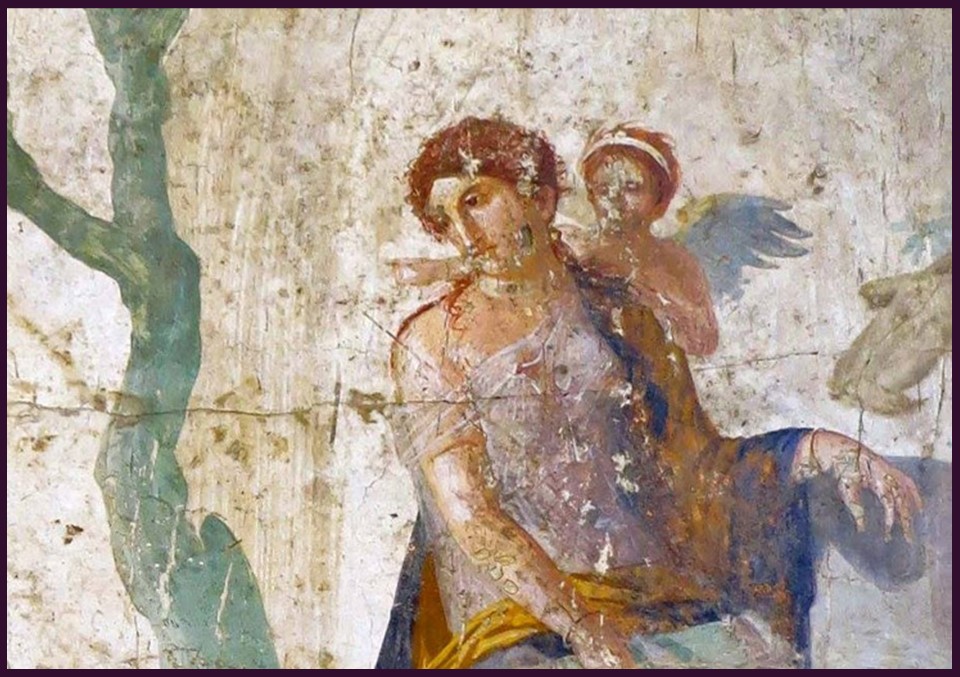

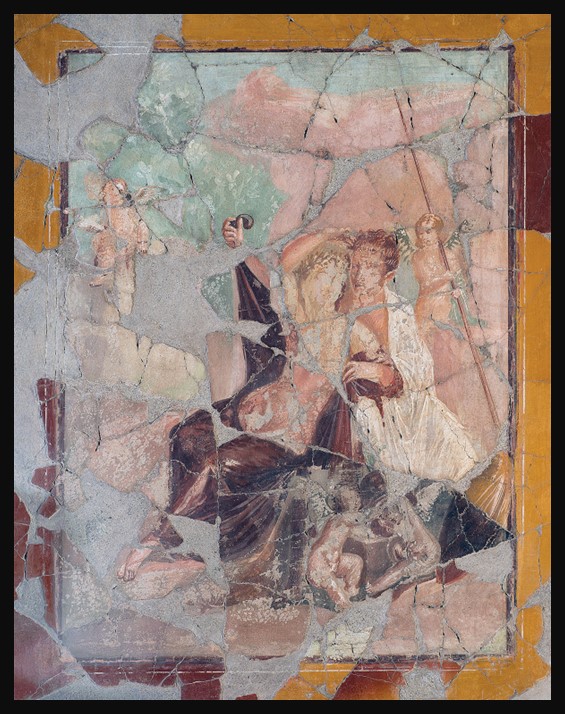

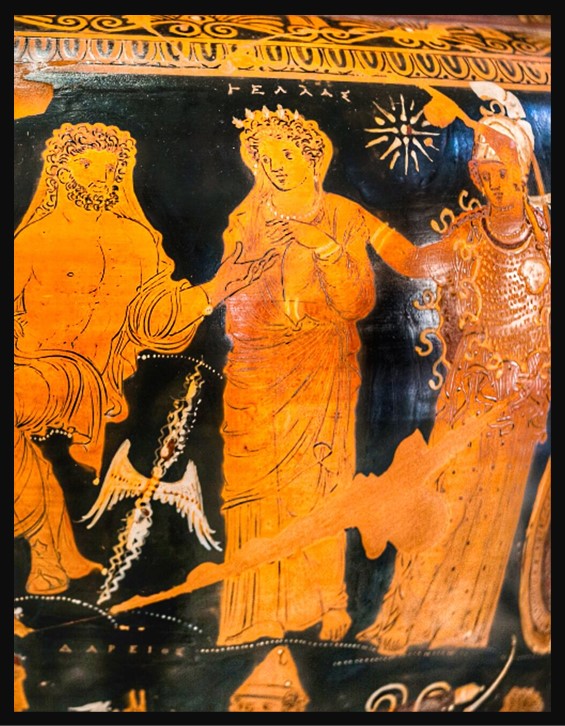

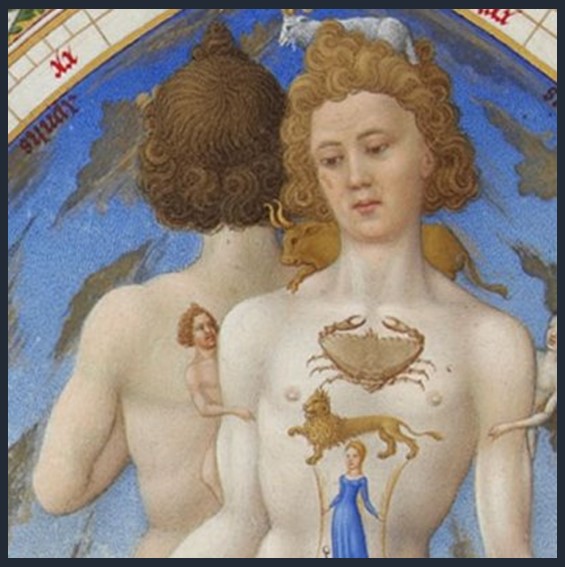

In Greek mythology, Pandora was the first woman on Earth. Created by the god Hephaestus at the request of Zeus, her creation was part of a divine punishment for humanity. This punishment was in retaliation for Prometheus, a Titan, who defied the gods by stealing fire and giving it to mankind. Endowed with gifts from each god and made irresistibly alluring to humans, Pandora was given in marriage to Epimetheus, the brother of Prometheus. Despite warnings from Prometheus not to accept any gifts from Zeus, Epimetheus accepted her. Pandora and Epimetheus thus became the first human couple. However, disaster loomed nearby. Driven by curiosity, Pandora opened a box she was forbidden to touch and released into the world all sorrows and death-bringers. Only Hope remained, trapped under the box’s lid, narrowly missing escape when Pandora hastily closed the lid. This calamity unfolded exactly as Zeus, the cloud-gatherer, had planned. Do Pandora’s actions illustrate the profound and often unintended consequences of human curiosity and disobedience?

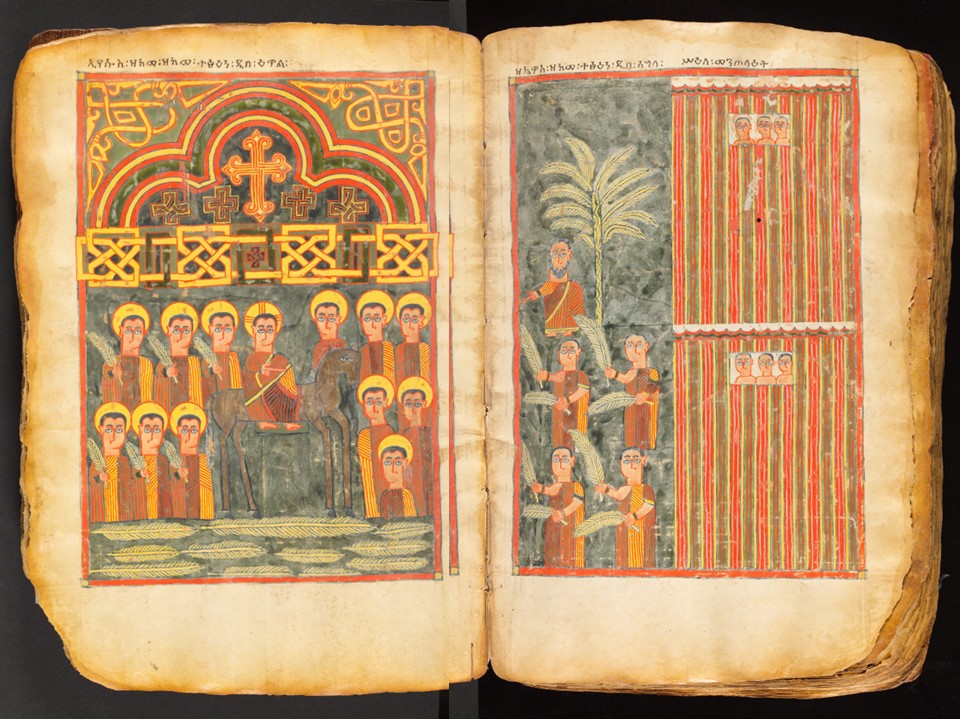

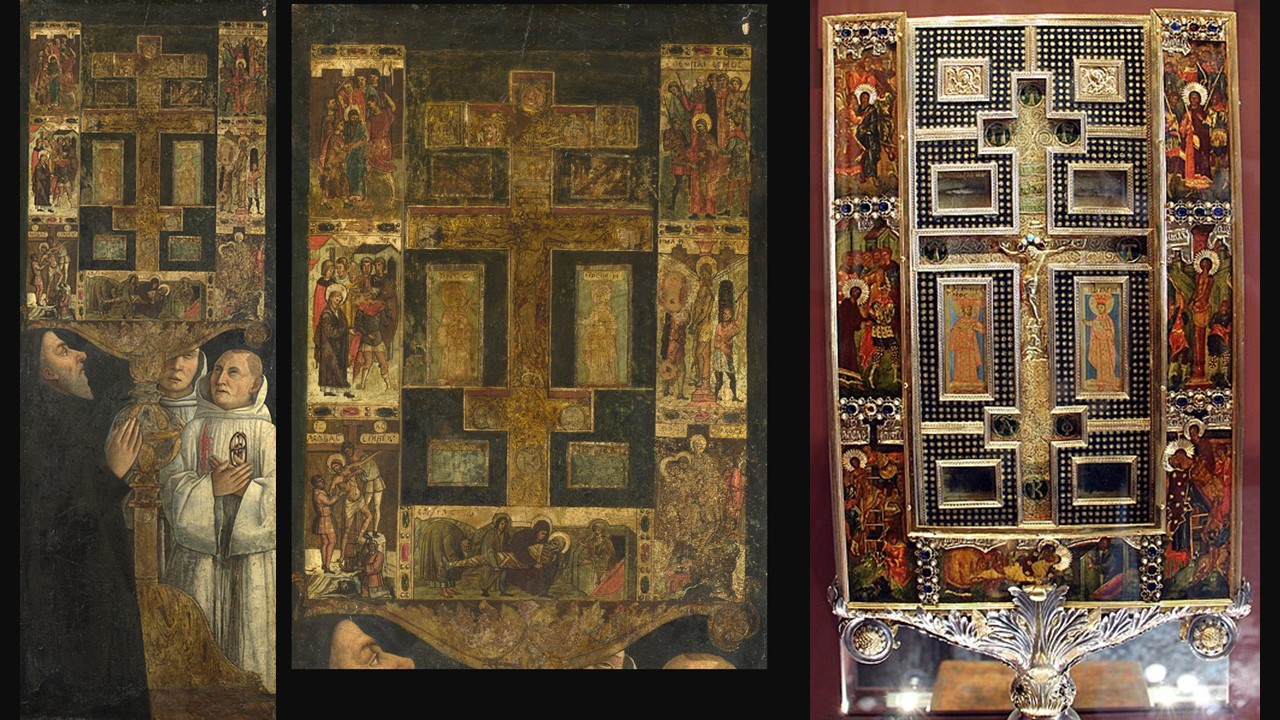

Domenicos Theotokopoulos, known as El Greco, was born in 1541 in Crete, which was then part of the Republic of Venice. Initially trained in the Byzantine tradition of icon painting, he moved to Venice around 1567, where he adopted elements of the Venetian Renaissance style under the influence of painters like Titian and Tintoretto. Seeking greater opportunities, El Greco relocated to Rome in 1570 and later moved to Toledo, Spain, in 1577, where he spent the remainder of his life. In Toledo, El Greco developed a distinctive style characterized by elongated figures and vibrant, expressive use of colour and light, often infused with dramatic spirituality. Despite his critical reception being mixed during his lifetime, El Greco is now celebrated as a precursor to both the Expressionist and Cubist movements, profoundly influencing the evolution of Western art. He died in 1614 in Toledo.

El Greco’s art is distinguished by its unique blend of Byzantine and Western painting traditions, resulting in a highly personal and spiritual style that pushed the boundaries of the Mannerist period. His figures are elongated and anatomically exaggerated, often imbued with a sense of spiritual intensity and inner turmoil that seems to stretch towards the divine. He used unconventional, vivid colour palettes and bold, almost expressionistic brush strokes that imbued his compositions with a dramatic, almost otherworldly quality. His treatment of light is particularly notable. It often seems to emanate from within the figures themselves, highlighting their ethereal and transcendent nature. This handling of form, colour, and light not only enhances the emotional depth and mystical atmosphere of his paintings but also foreshadows the emotional expressiveness of the Expressionist movement and the structural experimentation of Cubism, making El Greco a pivotal figure in the transition from the Renaissance ideals of harmony and proportion to the more subjective and distorted approaches of modern art.

The unique statues of Pandora and Epimetheus housed in the Prado Museum hold significant artistic and stylistic importance as they represent a rare excursion into sculpture by an artist renowned primarily for his paintings. These works are critical for understanding El Greco’s artistic language in a three-dimensional form, showcasing his ability to translate the intense emotionality and spiritual expressiveness characteristic of his paintings into sculpture. Stylistically, these statues exemplify his signature approach of elongation and dramatic posturing, traits that underscore his departure from conventional Renaissance forms and anticipate the emotional intensity of the Baroque period. The representation of such complex mythological figures in sculpture by El Greco adds a profound layer to the interpretation of his artistic legacy, demonstrating his innovative approach to volume, movement, and the human form, which challenged and expanded the aesthetic boundaries of his time.

Considering El Greco’s unique interpretive style and his known penchant for blending the spiritual with the human form, in what ways might his statues of a nude man and a nude woman be seen as symbolic representations of Pandora and Epimetheus? How do these sculptures reflect the themes of innocence, curiosity, and the inevitable consequences of human actions as depicted in the myth? …The woman removed the heavy lid of the jar with her own hands, and / driven by her own thoughts, unleashed sorrows for men, death-bringers. / Hope alone remained in its unbreakable home, / caught underneath the lip of the jar. Its escape / was only a short flight away, but, just in time, she slammed the lid down. / All according to the plan of aegis-bearing, cloud-gathering Zeus… https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/myths/chapter/lesson-5-primary-readings-prometheus-and-pandora/

For a PowerPoint Presentation titled, Domenikos Theotokopoulos, 10 Masterpieces, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/pandora/86a6b73f-8ef3-4132-aa68-4648a27a4b6a and https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/epimetheus/8abbfd9f-27f9-44b6-bbc6-e19854e7a69c