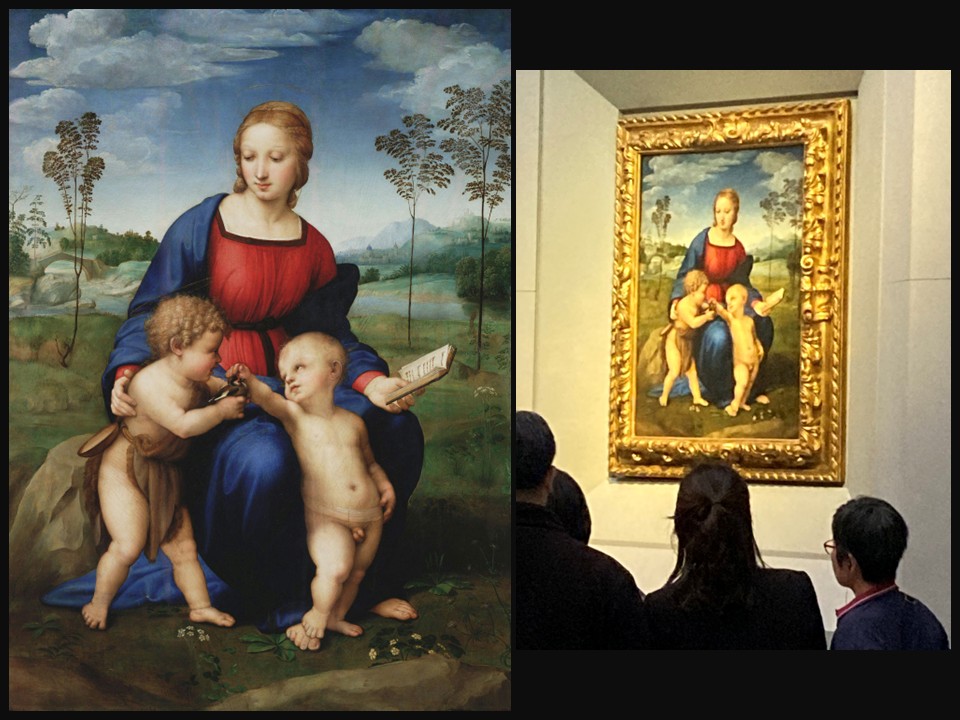

nd young Saint John the Baptist interact with a goldfinch, set against a serene Renaissance landscape. Left: https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/mary-christ-and-the-young-john-the-baptist-known-as-the-madonna-of-the-goldfinch – Right: Amalia Spiliakou, Galleria degli Uffizi, April 2025

Giorgio Vasari’s account of Raphael offers a tender glimpse into the origins of the Madonna of the Goldfinch, a painting born not from courtly commission but from friendship. Raphael, he writes, created the work as a gift for his close friend Lorenzo Nasi on the occasion of Nasi’s marriage. In it, the artist imagined the Virgin with the Christ Child receiving a small bird from the young John the Baptist, a simple gesture that fills the scene with childlike delight. Vasari praises not only the “infinite gladness” animating the two children, but also the Madonna’s serene grace and the meticulous beauty of the surrounding landscape. For Nasi, the painting became more than a wedding gift; it was a cherished reminder of his bond with Raphael and a testament to the work’s exceptional harmony, colour, and vitality.

Raphael’s ability to infuse sacred subjects with warmth and natural grace can be traced back to his formative years in Urbino, a cultured court where painting, poetry, and humanist learning thrived. Trained first in his father Giovanni Santi’s workshop, he absorbed an appreciation for harmonious composition and gentle narrative expression from an early age. His subsequent apprenticeship with Perugino refined his sense of clarity, balanced structure, and luminous colour, qualities that became hallmarks of his style. By the time Raphael arrived in Florence around 1504, he encountered the powerful artistic innovations of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, whose influence encouraged him to explore softer modelling, more intimate emotional exchanges, and deeper psychological unity among figures. The Madonna of the Goldfinch represents this synthesis beautifully: a youthful Raphael blending the serene Umbrian tradition with the expressive naturalism of the Florentine masters.

According to Vasari, Raphael’s friendship with Lorenzo Nasi shaped both the subject and the tenderness of the painting. Created to celebrate Nasi’s marriage, the Madonna of the Goldfinch is filled with domestic intimacy rather than grand theatricality. Raphael’s choice to centre the exchange of a small goldfinch, symbol of Christ’s future Passion, within a playful moment between children reflects a deliberate blending of personal affection and theological meaning. Vasari highlights how naturally the figures interact, noting the ‘childlike simplicity’ and harmony that Raphael captured with remarkable sensitivity. Seen through this lens, the painting becomes more than a devotional image; it is a poetic reflection of family, friendship, and new beginnings.

Vasari devotes particular praise to the painting’s execution, emphasising Raphael’s meticulous colouring and the almost lifelike presence of each figure. The Madonna’s serene posture and gentle divinity anchor the scene, while the landscape, finished with extraordinary care, envelops the figures in a calm, luminous world. Every detail, from the delicate modelling of the children’s faces to the soft transitions of light across the terrain, serves to heighten the emotional warmth of the composition. It is this marriage of technical finesse and human feeling, Vasari suggests, that made the work so precious to Nasi during his lifetime and continues to shape its enduring appeal.

Today, Madonna of the Goldfinch remains one of Raphael’s most beloved early masterpieces, treasured for the very qualities Vasari admired nearly five centuries ago: its luminous colour, its unforced naturalism, and the quiet poetry of its human relationships. Knowing the story behind its creation, the friendship with Lorenzo Nasi, the joyous domestic occasion it commemorated, and the admiration it inspired, allows us to see the painting not only as a work of art, but as a deeply personal gesture captured in paint. In Raphael’s hands, a simple exchange between children becomes a scene of spiritual tenderness and enduring beauty, inviting us, like Vasari, to marvel at how lifelike and heartfelt a painting can be.

For a PowerPoint Presentation, titled 10 paintings of the Madonna by Raphael, please… Click HERE!

Bibliography: Vasari’s biography of Raphael http://www.artist-biography.info/artist/raphael/ and from the Uffizi Museum official site https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/mary-christ-and-the-young-john-the-baptist-known-as-the-madonna-of-the-goldfinch and from Visit Tuscany site https://www.visittuscany.com/en/attractions/madonna-del-cardellino-by-raphael/