Tea-Pot shaped as a Hare, c. 1882, Silver and Ivory, Height: 12,8 cm, Length: 24,8 cm, Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay), Paris, France

https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/theiere-19279

The Musée d’Orsay’s remarkable Hare-shaped Teapot, designed by Émile Auguste Reiber in the late nineteenth century, is one of the most striking expressions of Japonism in European decorative arts. Inspired by Meiji-period bronzes and the asymmetrical, nature-infused aesthetics that captivated Parisian artists of the era, Reiber transformed a functional object into a playful yet sophisticated sculptural form. The teapot’s lively silhouette, delicate modeling, and distinctly Japanese sensibility reveal how deeply Western designers absorbed, and reimagined, the visual language of Japan, making this whimsical hare an elegant gateway into the broader story of Japonism’s influence on modern design.

Japonism took hold in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Japan’s opening to international trade introduced Western artists to an entirely new visual world. Woodblock prints, lacquerware, ceramics, and metalwork arrived in Paris with a force that felt both exotic and revelatory. Their asymmetrical compositions, expressive natural forms, and emphasis on surface pattern challenged the conventions of classical European design. Artists such as Whistler, Monet, Degas, and van Gogh absorbed these influences eagerly, while designers and craftsmen began to experiment with Japanese motifs and techniques in furniture, textiles, and decorative objects. Japonism was not simply a fleeting fashion: it reshaped the visual vocabulary of European art at a moment when tradition itself was being questioned.

In the decorative arts especially, Japan offered a model for integrating beauty, utility, and imagination. French designers found in Japanese metalwork a bold alternative to the rigid historicism that had dominated European taste. Animal-shaped vessels, fantastical spouts, and organic silhouettes, forms common in Meiji bronzes, became catalysts for creative reinvention. Émile Reiber’s Hare-shaped Teapot embodies this shift perfectly: it is not a direct copy of a Japanese object, but a spirited reinterpretation that channels the wit, naturalism, and sculptural freedom of Japanese design. In this sense, the piece serves as a microcosm of Japonism itself, a dialogue between cultures that sparked innovation and broadened the horizons of modern European art.

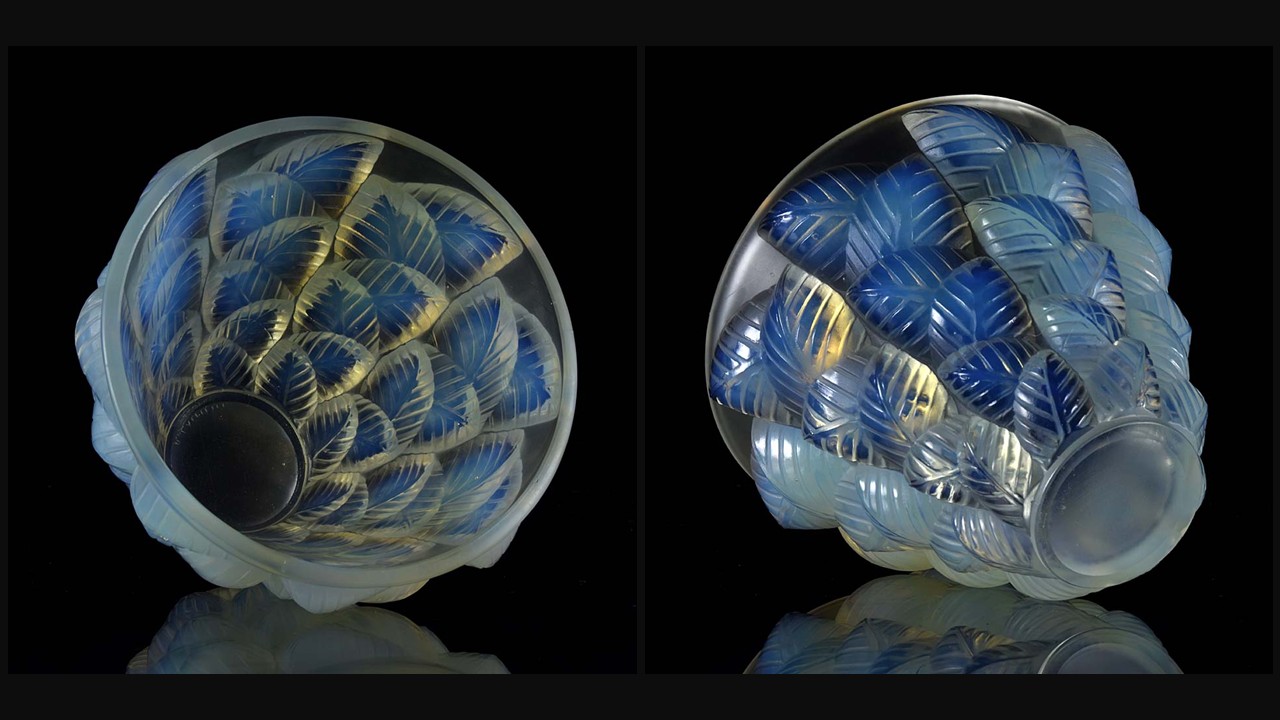

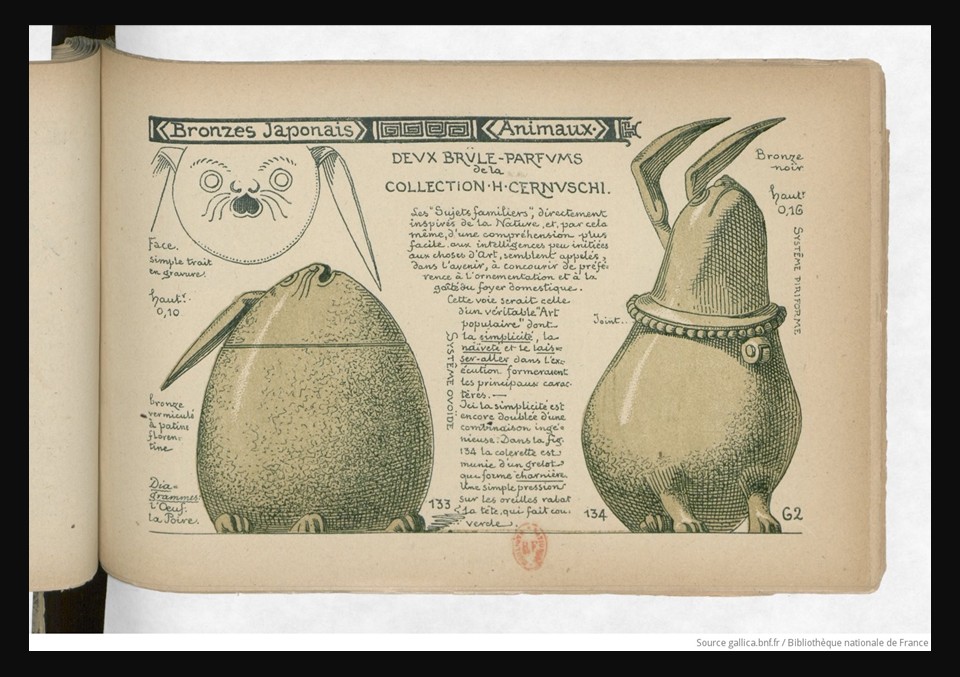

Le premier volume des albums-Reiber: bibliothèque portative des arts du dessin, Page 62

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k938496c/f210.item

Reiber’s Teapot at the Musée d’Orsay brings these broader currents of Japonism into vivid, tangible form. Conceived as a functional object animated by the body of a crouching hare, it transforms the animal’s rounded torso into the vessel itself, while its alert ears and coiled limbs lend the piece an almost kinetic presence. This inventive silhouette traces directly to Reiber’s encounters with Japanese bronzes in the celebrated collection of Henry Cernuschi, whose holdings offered European designers unprecedented access to East Asian metalwork. Reiber studied these objects closely, publishing drawings of them in his Albums Reiber of 1877, and was especially drawn to the smooth, ovoid incense burners and whimsical animal figures that embodied an entirely different approach to form and ornament.

Seen in this light, the hare teapot becomes more than an amusing curiosity: it crystallizes Reiber’s belief that everyday objects could be enlivened through natural forms and infused with a sense of humor and simplicity. His conviction that such designs could bring ‘decoration and gaiety’ into domestic life aligned perfectly with Japonism’s broader embrace of artistic freedom and cross-cultural inspiration. By reimagining the spirit rather than the exact form of Meiji bronzes, Reiber created an object that is at once French in execution and profoundly shaped by Japanese aesthetics. The teapot thus stands as a small but eloquent emblem of Japonism’s transformative power, a reminder of how the encounter with Japan encouraged European designers to see function, nature, and beauty in new and delightfully unexpected ways.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Émile Auguste Reiber’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Émile-Auguste Reiber’s Le Premier Volume des Albums-Reiber (1877) is a key historical collection of design motifs and drawings, offering rich visual documentation that supports and enriches the research on The Musée d’Orsay’s remarkable Hare-shaped Teapot Blog Post… https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k938496c/f210.item

Bibliography: from the Musée d’Orsay https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/theiere-19279 and https://amis-musee-cernuschi.org/en/japon-japonismes-objets-inspires-1867-2018-3/ and Christie’s https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/collections-provenant-des-familles-cosse-brissac-dormesson-la-bedoyere/theiere-lievre-en-metal-argente-209/274015?ldp_breadcrumb=back