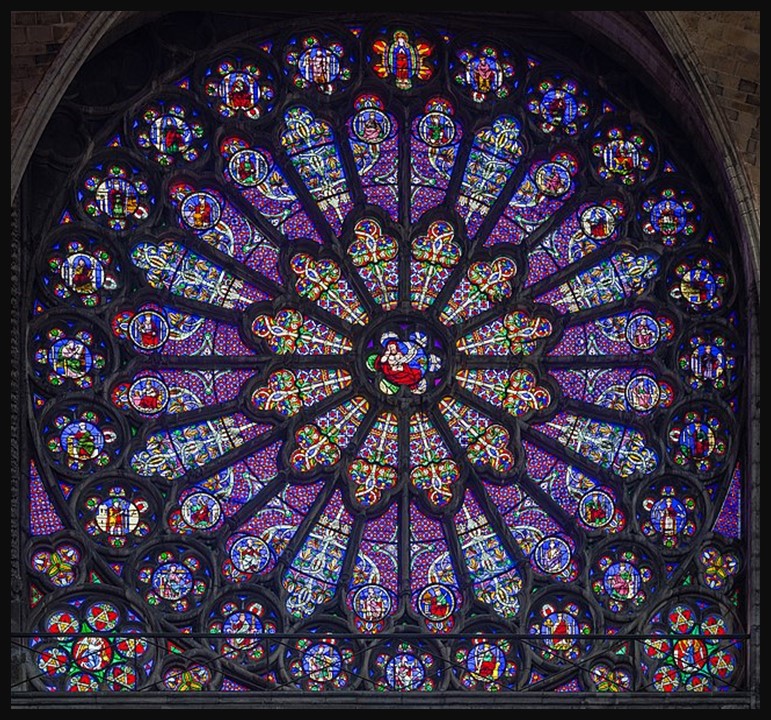

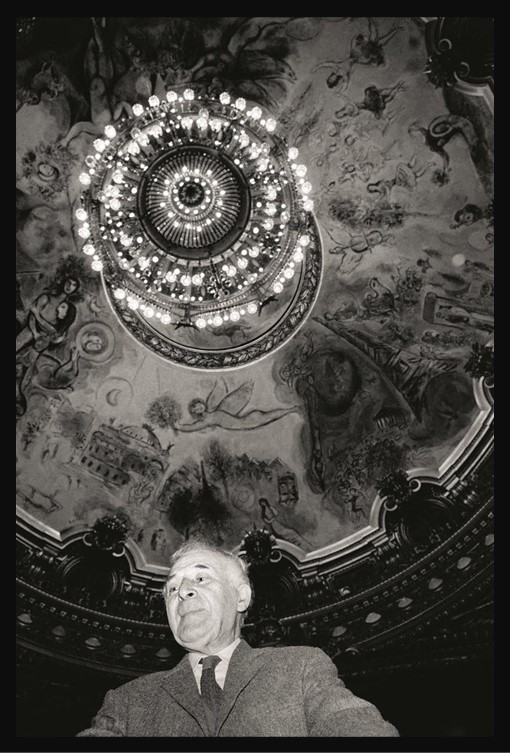

The ceiling of the Opéra Garnier, started in 1963 and completed on the 23rd of September, 1964, nearly 240 m² canvas, Opera Garnier, Paris, France – Photo Credit: Amalia Spiliakou, May 8, 2023

Russian-born artist Marc Chagall once said that “the dignity of the artist lies in his duty of keeping awake the sense of wonder in the world.” And it is difficult to conceal one’s wonder beneath Chagall’s magnificent ceiling at the Opéra Garnier, a masterwork that was unveiled in 1964… This is exactly how I felt on the 8th of May, 2023, attending the Dante Project by Wayne McGregor… WONDER! https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/marc-chagall-opera-ceiling

Today’s goal is to highlight the artistic significance of the Opera Garnier’s painted Dome, featuring the breathtaking work of renowned painter Marc Chagall.

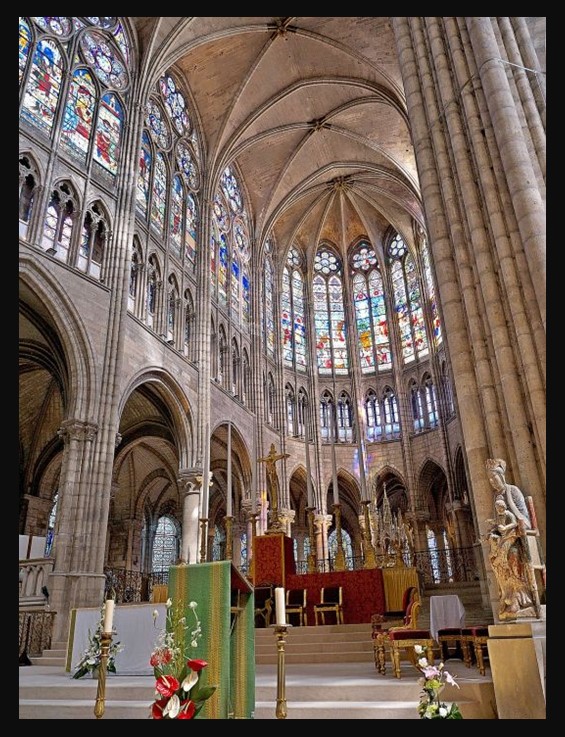

Chagall’s work at the Opera Garnier in Paris stands as a captivating testament to artistic innovation within the confines of historical grandeur. The vivid colors and imaginative forms of Chagall’s masterpiece create a striking juxtaposition against the backdrop of the Belle Epoque building. As one gazes upon the ornate details and classical elegance of the Opera House, the unexpected burst of modernity and expression on the dome becomes a mesmerizing focal point. This dynamic interplay between tradition and avant-garde artistry enhances the overall aesthetic experience, inviting viewers to appreciate the harmonious coexistence of two distinct yet complementary artistic worlds within the iconic Parisian landmark.

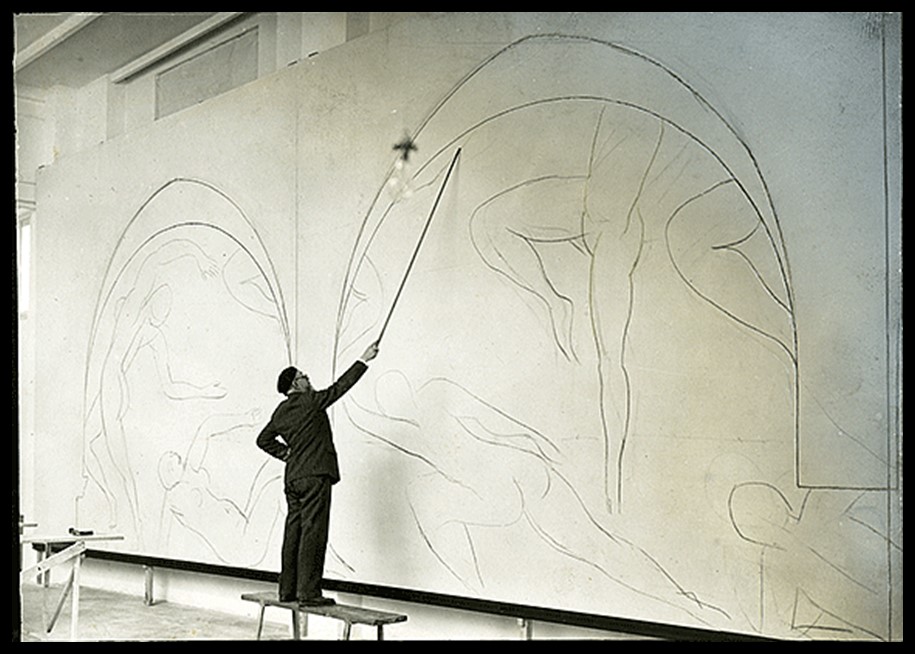

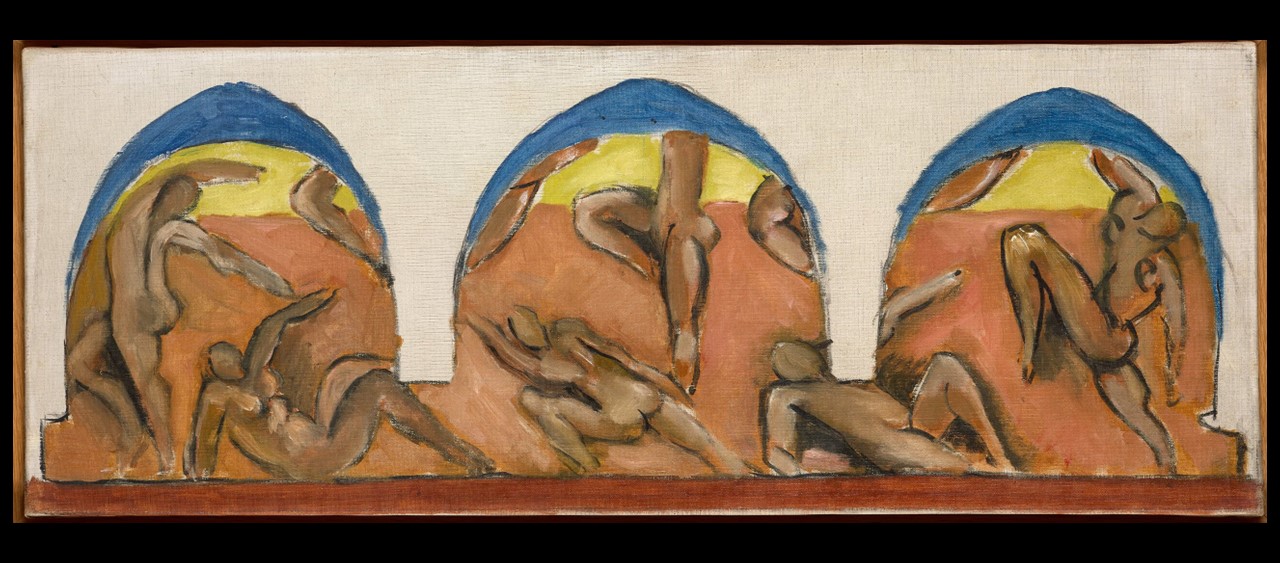

Marc Chagall’s involvement in painting the dome of the Opera Garnier in Paris is a fascinating chapter in the history of both art and architecture. In 1963, French Minister of Culture André Malraux proposed the idea of commissioning a contemporary artist to contribute to the decoration of the historic building. Chagall, renowned for his dreamlike and symbolic works, was chosen for this ambitious project, hoping for this commission to mark a departure from the conventional approach of adorning opera houses with historical or mythological themes. The artist embraced the opportunity to infuse the space with his distinctive blend of colors and imaginative compositions. He embarked on the task with great enthusiasm, creating a 560-square-meter masterpiece that would become one of his largest and most celebrated works.

Completed in 1964, Chagall’s painted dome is a visual feast, featuring a rich tapestry of scenes and characters from famous operas. The vibrant hues and dynamic forms evoke a sense of lyricism and movement, encapsulating the essence of the performing arts.

The theme behind Marc Chagall’s painting of the dome of the Opera Garnier is a celebration of the world of music, dance, and the performing arts. Chagall’s approach to the commission was to create a vibrant and whimsical visual narrative that captured the spirit of opera and ballet. The dome serves as a vast canvas for Chagall’s imaginative interpretation of the cultural and emotional resonance found in the world of performing arts, featuring a kaleidoscope of colors, floating figures, and symbolic elements drawn from various operas. Dancers, musicians, and mythical creatures come together in a dreamlike composition, conveying a sense of lyricism and movement. The artist skillfully weaves together scenes and characters from famous operas, creating a harmonious and dynamic tapestry that reflects the magic and drama of the performing arts.

The ceiling of the Opéra Garnier started in 1963 and was completed on the 23rd of September, 1964, nearly 240 m² canvas, Opera Garnier, Paris, France https://www.pariszigzag.fr/insolite/histoire-insolite-paris/lhistoire-du-plafond-de-lopera-garnier-par-marc-chagall

Chagall’s dome at the Opera Garnier received mixed reactions initially, with some critics appreciating the modern approach and others expressing reservations about its departure from tradition. However, over time, the masterpiece has come to be recognized as a pivotal work in the intersection of contemporary art and historic architecture. Today, Chagall’s contribution to the Opera Garnier stands as a testament to the enduring power of artistic expression and the willingness to embrace innovation within venerable cultural institutions. The painted dome continues to enchant visitors, offering a unique and immersive experience that transcends the boundaries of time and tradition.

For a Student Activity, inspired by Chagall’s magnificent ceiling at the Opéra Garnier, please… Check HERE!

Opéra Garnier in Paris filmed by a drone… is an interesting, short, video to watch: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/marc-chagall-opera-love-never-died-look-paris-op%C3%A9ra-garnier-cruz-1/

On Marc Chagall: The artist of the Opera’s dome, Marc Chagall, was of Russian-French origin, known for his unique blend of fantasy, symbolism, and elements of folk art. He was associated with several art movements, including Cubism and Surrealism, but his work defied easy categorization. Chagall’s art often featured dreamlike and poetic scenes, filled with vibrant colors and floating figures. He painted a variety of subjects, including village life, biblical themes, and memories of his hometown Vitebsk. Marc Chagall’s contributions to the art world have left a lasting impact, and he is considered one of the most significant artists of the 20th century.

On the Opera Garnier: Officially known as the Palais Garnier, this is an architectural masterpiece and a cultural icon located in the heart of Paris, France. Designed by Charles Garnier and inaugurated in 1875, the opera house is a splendid example of Beaux-Arts architecture, characterized by its opulent ornamentation, grandiosity, and meticulous attention to detail. The exterior is adorned with sculptures, columns, and a grand staircase, while the interior boasts a lavish auditorium with a stunning chandelier, intricate frescoes, and a ceiling painted by Marc Chagall in the 1960s. The Opera Garnier has been a focal point for Parisian cultural life, hosting a myriad of operas, ballets, and other performances. Its rich history, architectural beauty, and artistic significance make it a symbol of Paris’s enduring cultural legacy.