https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/469960

Step into the symbolic world of Late Antiquity through this remarkable mosaic fragment portraying Ktisis, the ancient personification of creation, foundation, and civic generosity. With her richly ornamented garments, expressive gaze, and accompanying figure holding a cornucopia, she embodies the ideals of prosperity and well-ordered society. Once part of an elegant floor, this mosaic invites us to reflect on how art, mythology, and civic identity were woven seamlessly into daily life in the ancient Mediterranean.

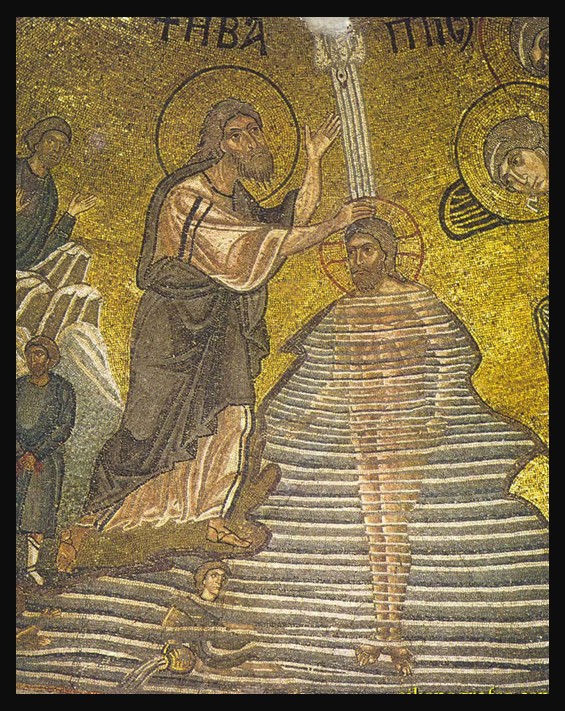

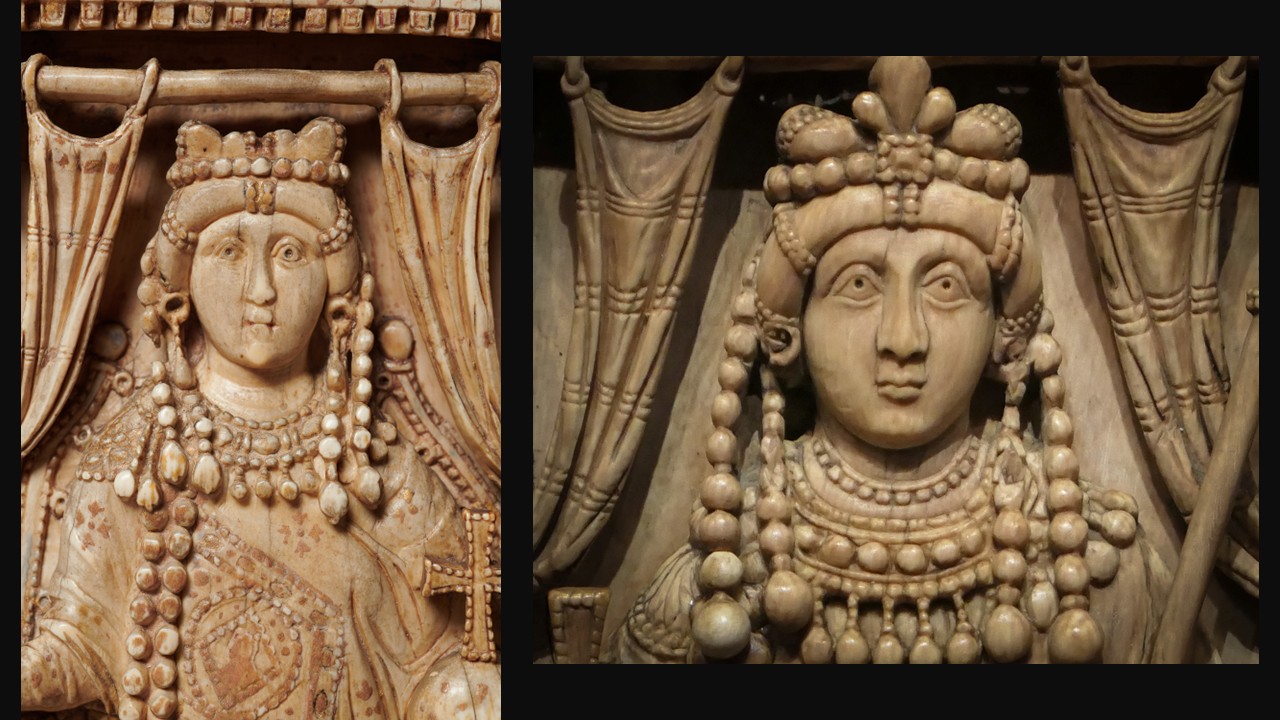

At the center of the composition appears the personification of Ktisis, depicted frontally with large, expressive eyes that engage the viewer directly and lend the figure a commanding, almost iconic presence. Her softly modeled face is framed by carefully arranged curls and crowned with a jeweled headband, details that underscore refinement and elevated status. She wears a richly patterned garment fastened with an ornate necklace, the dense ornamentation and shimmering tesserae emphasizing dignity, wealth, and abundance. In her hand she holds a Roman copper tool called a foot ruler, a clear visual sign of engineering closely tied to her symbolic role. The Greek inscription naming Ktisis identifies her unambiguously, guiding the viewer’s interpretation of the scene. To the left, a smaller standing male figure advances toward her holding a cornucopia, the classical emblem of plenty; an inscription beside him identifies his role and further clarifies the allegorical program of the mosaic. Scholars have suggested that Ktisis was originally flanked symmetrically by a second small male figure on her right, now lost, which would have created a more balanced composition emphasizing abundance and benefaction on both sides. Even in its fragmentary state, the surviving figure establishes a subtle narrative exchange that reinforces themes of prosperity, order, and civic well-being while enlivening the scene.

In late antiquity, Ktisis embodied the concepts of foundation, creation, and benefaction. She was closely associated with the act of building and with the generosity of patrons who endowed structures for private or communal use. Her presence in a floor mosaic would have communicated prosperity, stability, and divine or civic favor, transforming the architectural space into a visual statement of success and legitimacy.

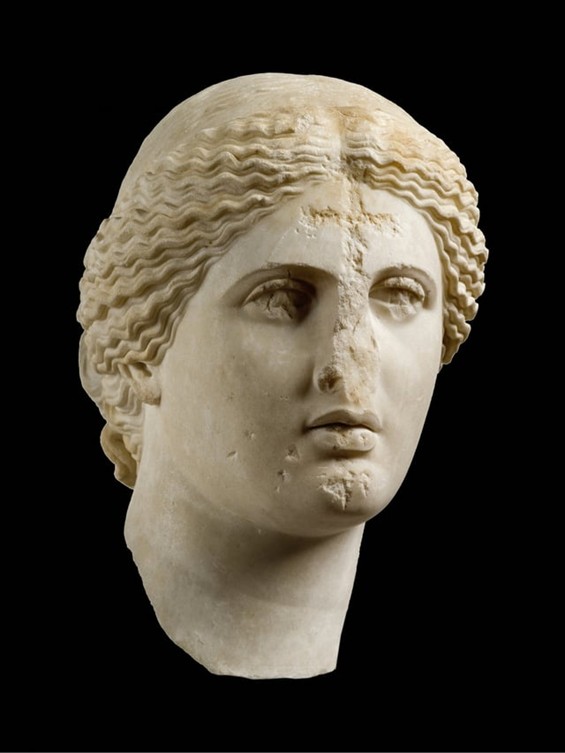

Stylistically, the mosaic reflects a transitional moment between classical naturalism and the emerging Byzantine aesthetic. Subtle modeling of the face coexists with an increasingly abstracted body and decorative emphasis on surface pattern. The shimmering marble and glass tesserae enhance the figure’s presence, while the frontal pose and enlarged eyes anticipate later Byzantine iconography.

As a floor mosaic, this image would have been encountered from above and at close range, integrated into the rhythm of daily movement. Walking across the figure of Ktisis reinforced her symbolic role: prosperity and benefaction quite literally underfoot, embedded in the fabric of the building itself. The mosaic thus functioned not only as decoration but as a constant visual assertion of order and well-being.

Seen today as a fragment and displayed vertically, the mosaic invites a different kind of engagement. Removed from its architectural setting, it becomes an object of focused contemplation rather than lived experience. Yet even in isolation, the figure of Ktisis continues to speak eloquently about late antique values, patronage, and the evolving language of Byzantine art.

For a Student Activity inspired by the Roman Foot Ruler, please… Check HERE!

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Activities created by my students, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/469960 and Dr. Evan Freeman and Dr. Anne McClanan, “Byzantine Mosaic of a Personification, Ktisis,” in Smarthistory, February 3, 2020, accessed December 11, 2025, from smarthistory https://smarthistory.org/byzantine-ktisis/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsvOinFR1qs and Personifications of KTISIS in early Byzantine mosaics, by Rederic Lecut, and from Academia https://www.academia.edu/42068332/Personifications_of_KTISIS_in_early_Byzantine_mosaics