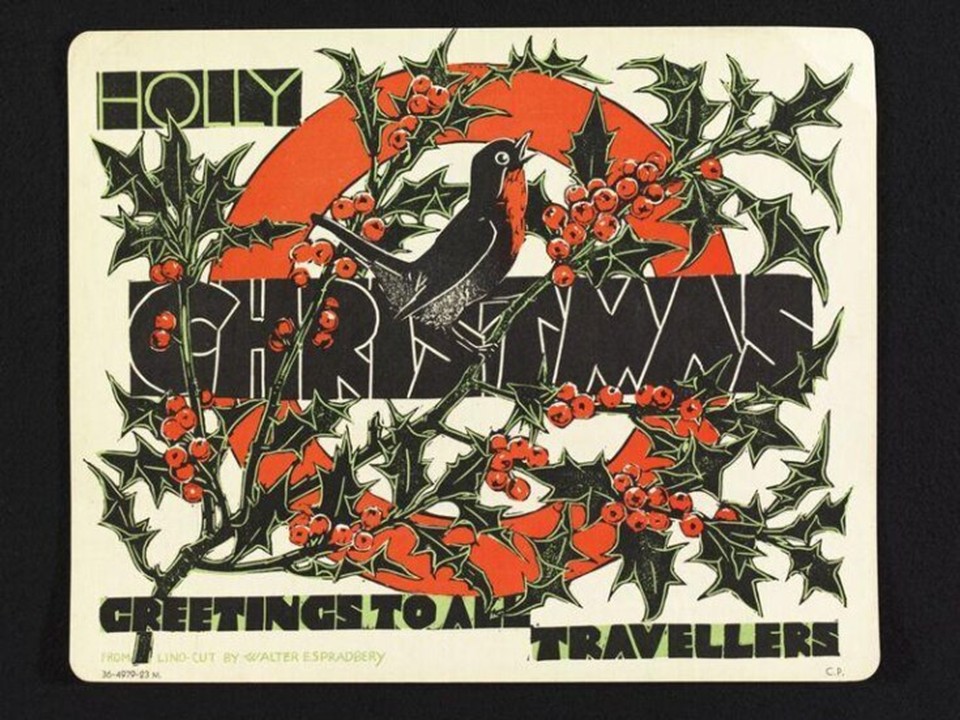

Issued by: Underground Electric Railways Company of London Ltd

Holly, 1936, Small format Poster, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1023797/holly-poster-spradbery-walter-e/

Walter E. Spradbery’s Holly is a vibrant 1936 linocut poster commissioned by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London Ltd., embodying the festive spirit of Christmas while promoting travel on the London Underground. The artwork blends traditional holiday imagery, holly leaves, red berries, and a robin, with bold Art Deco typography and modern design sensibilities. Spradbery’s masterful use of color and composition not only celebrates seasonal joy but also reflects the company’s commitment to combining art and public transport, turning everyday journeys into opportunities for cultural enrichment.

Spradbery was an English artist, designer, and poet best known for his work as a poster artist during the early to mid-20th century. Born in London, he studied at the Walthamstow School of Art and later taught there, becoming a key figure in promoting art and design education. Spradbery served in the First World War as an official war artist, where his experiences deeply influenced his artistic outlook, emphasizing themes of resilience and beauty amid adversity. After the war, he continued to work prolifically as an illustrator, muralist, and printmaker, developing a distinctive style rooted in linocut printing and strong design principles.

Spradbery’s collaboration with major British transport companies, including the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER), Southern Railway, and London Transport (LT), played a central role in his career. His posters were part of a broader movement to use fine art to promote public travel, encouraging leisure and exploration through visually compelling imagery. For the LNER and Southern Railway, he created scenes that celebrated the beauty of the British landscape, inviting passengers to discover the countryside and coastlines by rail. For London Transport, Spradbery designed posters that combined practical information with artistic flair, often highlighting seasonal themes, gardens, and historical landmarks, thereby helping to shape the visual identity of public transport in the interwar period.

Aesthetically, Spradbery’s work is characterized by bold composition, rhythmic linework, and vibrant color contrasts, often achieved through his skilled use of the linocut technique. His designs fuse natural motifs, trees, flowers, birds, and architectural forms, with modern graphic design principles, creating images that feel both decorative and dynamic. Influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and early modernism, Spradbery’s posters convey a sense of optimism and harmony between nature, art, and modern life. His works, including Holly, embody a timeless appeal, blending craftsmanship with a democratic vision of art accessible to the public through everyday encounters in stations and trains.

In his 1936 poster Holly, issued for the Underground Electric Railways Company of London Ltd., Walter E. Spradbery transforms a familiar seasonal motif into a striking graphic composition. Set against the stylised red ‘O’ of London Underground’s iconic roundel, a vibrant sprig of holly with lush green leaves and bright red berries encircles a singing robin at its centre. The design is executed as a bold linocut and retains the crisp simplicity of the technique, offering clear, high-contrast shapes and limited colour fields that draw the eye in. With the text ‘HOLLY CHRISTMAS GREETINGS TO ALL TRAVELLERS’ the poster functions both as a festive greeting and a visual invitation to travel, merging holiday cheer with the everyday mobility of London’s transport system. The piece is emblematic of Spradbery’s ability to unite artistic elegance with commercial purpose, turning a public-transport poster into an object of design worth preserving.

As December’s ‘Plant of the Month,’ Holly stands as a timeless symbol of resilience, renewal, and festive cheer, its evergreen leaves and bright red berries capturing the spirit of the season, Walter E. Spradbery’s Holly beautifully encapsulates these associations, blending art, nature, and celebration into a single uplifting image. Just as his 1936 poster wished ‘greetings to all travellers,’ we too can carry forward that message of warmth and goodwill. May this December bring you peace, creativity, and joy as we journey together into the festive season and the promise of a new year.

For a PowerPoint Presentation on Walter E. Spradbery’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1023797/holly-poster-spradbery-walter-e/ and https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/stories/design/walter-ernest-spradbery-artist-war-and-peace