View of Venice, c. 1883, Oil on Canvas, 32.4 x 40.6 cm, Private Collection

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6519611?ldp_breadcrumb=back

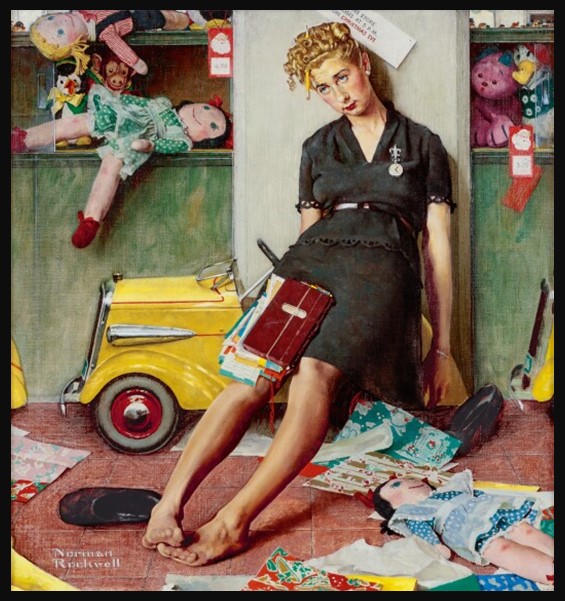

When Childe Hassam set out on his first extended European journey in the summer of 1883, he was still a young Boston-based illustrator searching for his artistic voice. Accompanied by fellow painter Edmund H. Garrett, he traveled through Great Britain, France, Spain, the Netherlands, and Italy, absorbing everything from atmospheric city scenes to masterworks in museums. Venice was among the places that captivated him most deeply. Shimmering light, reflected architecture, and a city arranged on water offered a visual language he had not yet encountered in America. Looking back on this formative trip, Hassam later wrote: “I made my sketches from nature in watercolor and I used no white. It was this method which led me into the paths of pure color… When I turned to oils, I endeavored to keep my color as vibrant.” This reflection offers a perfect lens through which to enjoy View of Venice, painted around that pivotal moment in his early career.

View of Venice and the Emergence of American Impressionism

View of Venice is a small but luminous work that captures the essence of the floating city with youthful immediacy. A gondola glides across the lagoon, fruit sellers animate the foreground, and a soaring campanile anchors the horizon, not as a monumental landmark, but as part of a living environment. Hassam’s brushwork dispenses with tight detail and instead pursues fleeting effects of atmosphere. Reflections tremble on the water’s surface; sunlight flickers across sails, stones, and faces. This sensitivity to shimmering light and transient impressions would soon become hallmarks of his mature style, but here we see it in its early, exploratory form.

Although Hassam would later refine his Impressionist language during his Paris years (1886–1889), View of Venice already reveals his fundamental shift from illustration to a modern painterly vision. His interest lies not in the grand, theatrical Venice of Canaletto, but in the lived-in Venice of ordinary people, canal traffic, and the play of natural light. It reflects the emerging belief, one he often articulated, that the modern artist should paint the world as it appears in the moment, with spontaneity and personal perception guiding the hand.

The painting’s recent appearance at Christie’s reaffirms its significance within Hassam’s development. Far from being a minor travel sketch, View of Venice represents one of the earliest surviving examples of his European awakening, a moment when he began to shed the conventions of American illustration in favor of the freer, color-driven vocabulary that would later define his career. Its provenance, stretching from early Boston collections to a Pennsylvania private estate, adds a layer of continuity: View of Venice has long been cherished as a document of transformation.

Venice itself continued to echo through Hassam’s later works. Whether painting urban New York, New England harbors, or quiet coastal views, he repeatedly explored the interplay of water, sky, architecture, and modern life. The atmospheric sensibility first awakened in the Venetian lagoon never left him. Seen in this light, View of Venice is more than an early experiment, it is a seed from which much of his later brilliance grew.

Today, this painting invites us to see Venice not as a fragile relic or tourist symbol, but as a vibrant, ever-changing stage for color and life. Through Hassam’s eyes, we experience the city with the wonder of a young artist standing at the threshold of discovery. View of Venice remains a testament to the transformative power of travel, observation, and the courage to embrace a new artistic path, a message as resonant now as it was in 1883.

For a PowerPoint Presentation of Childe Hassam’s oeuvre, please… Check HERE!

Childe Hassam remains one of the most important figures in American Impressionism. In this former Teacher Curator post, I examine another of his paintings, situating it within his broader artistic development and exploring how light, atmosphere, and everyday life define his style. Please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: According to Christie’s catalogue entry https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6519611?ldp_breadcrumb=back