The Dance (view of the Main Room, South Wall), Summer 1932 – April 1933, Oil on canvas; three panels, Overall (left): 339.7 x 441.3 cm, Overall (center): 355.9 x 503.2 cm, Overall (right): 338.8 x 439.4 cm, the Barnes, Philadelphia, PA, USA https://collection.barnesfoundation.org/objects/6967/The-Dance/ensemble

My new BLOG POST titled The Dance by Matisse at the Barnes Foundation starts by quoting Professor Yve-Alain Bois, how Matisse himself describes, on two separate accounts, the moment at which he began work on the Barnes Dance composition and the immensity of the surface he had to master or as he phrased it ‘to possess’…. In the first version, it is an architectural rhyme that triggers the onset of this sense of possession: ‘ As I was pacing in front of my seventy-two square meters of white canvas destined to become the decoration of Doctor Barnes, not knowing which way to start, I noticed by chance a rope hanging from a window to a random spot in my studio, standing out and projecting a curve on my canvas. I suddenly had before me the relationship of this curve to the great rectangle of the edges of my decoration.

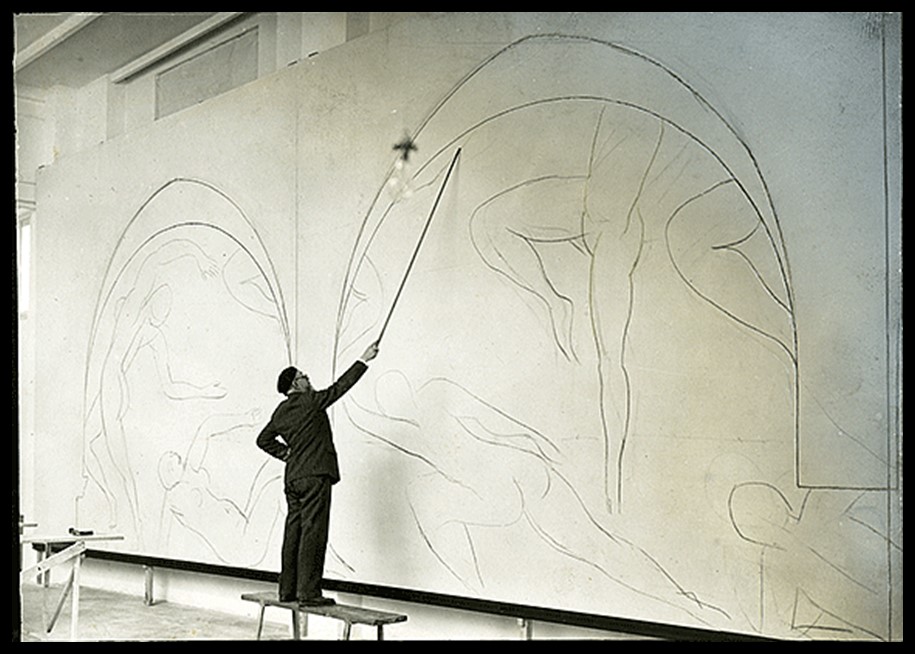

Henri Matisse using a bamboo stick to sketch The Dance in his studio in Nice, 1931, Photograph Collection, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia

https://www.ias.edu/ideas/2016/bois-matisse-barnes

The second documented account, once more quoting Professor Yve-Alain Bois, of what kicked off Matisse’s sense of taking possession, of the immensity of the space he had to cover, is perhaps more surprising than the first… ‘Faced with my huge white canvases, Matisse wrote, I took a model and began a study that had nothing to do with the decoration. At each of the model’s breaks, I relaxed by looking at these great surfaces, absentmindedly—or so I thought. Then, at a certain point, there came a flash of inspiration. I took my big charcoal, attached it to the end of a big bamboo, and began drawing the circle of my dancers, from one end to the other of my thirteen-meter surface. I’d got off the mark, taken possession of my surface entirely through the power of my imagination. That’s how I made my painting: entirely from feeling, without a model.’

It was the 27th of September, 1930, when Matisse, while touring the United States by train, made a detour to the Barnes Foundation because it housed a significant number of his artworks. He was a man in trouble… I have made several attempts to paint, he wrote to his daughter, Marguerite, in 1929, but when faced with the canvas, I find myself devoid of inspiration… The once-upon-a-time enfant terrible experienced a disheartening period of creative stagnation.

The artist was 60 years old, and lived in Nice, for the past thirteen years. Employing vibrant patterns and radiant colors illuminated by the Mediterranean light, he found himself falling into a repetitive style, capturing captivating female models within the confines of his studio. By 1927, certain critics questioned whether this once-radical artist had lost his innovative spark. They were wondering whether the aging painter of the odalisques was the man André Breton described as ‘a discouraging and discouraged old lion’.

Back in Philadelphia, in September of 1930, visiting the Barnes Foundation, and talking with its founder and owner, Dr. Albert Barnes, Matisse’s creativity ‘issue’ was put to test… According to Cynthia Carolan, a docent at the Barnes Foundation, Dr. Barnes approached the aging painter, engaged him in a gentle critique of his Nice paintings, and acknowledged their sensuous and captivating nature, but suggested they lacked the weightiness of his earlier works. Then, the collector extended an invitation to Matisse, offering him a commission to create a painting that would suit the lunettes, the grand arches above the windows, on the southeast wall of his newly established gallery.

It was a challenge Matisse could not refuse. It would be the only commissioned artwork within the Barnes collection, created specifically for an architectural area of the building. It was a ‘grand’ project as he was expected to create a ‘mural’ in a space that spanned a width of approximately 13.7 meters. It would consist of three distinct canvases, with borders that would converge. Barnes gave Matisse free rein in the choice of subject matter; the agreement simply specified the size of the mural and its place on the southeast wall of the Main Gallery. For Matisse, who had never created anything this large, it was a new beginning!

The Dance, Summer 1932 – April 1933, Oil on canvas; three panels, Overall (left): 339.7 x 441.3 cm, Overall (center): 355.9 x 503.2 cm, Overall (right): 338.8 x 439.4 cm, the Barnes, Philadelphia, PA, USA https://collection.barnesfoundation.org/objects/6967/The-Dance/

Matisse soon chose the subject of The Dance to embellish the three arches that extended above the French windows. The motif represented an expression of vitality and rejuvenation, a theme that had preoccupied him since he was inspired by the sight of the Catalan fishermen dancing the sardaña on the beach at Collioure in the summer of 1905. He rented the space of an old garage, big enough to work on the outsized canvases, turned to his 1909 and 1910 paintings of Dance 1 and Dance II for inspiration… and started facing the challenges!

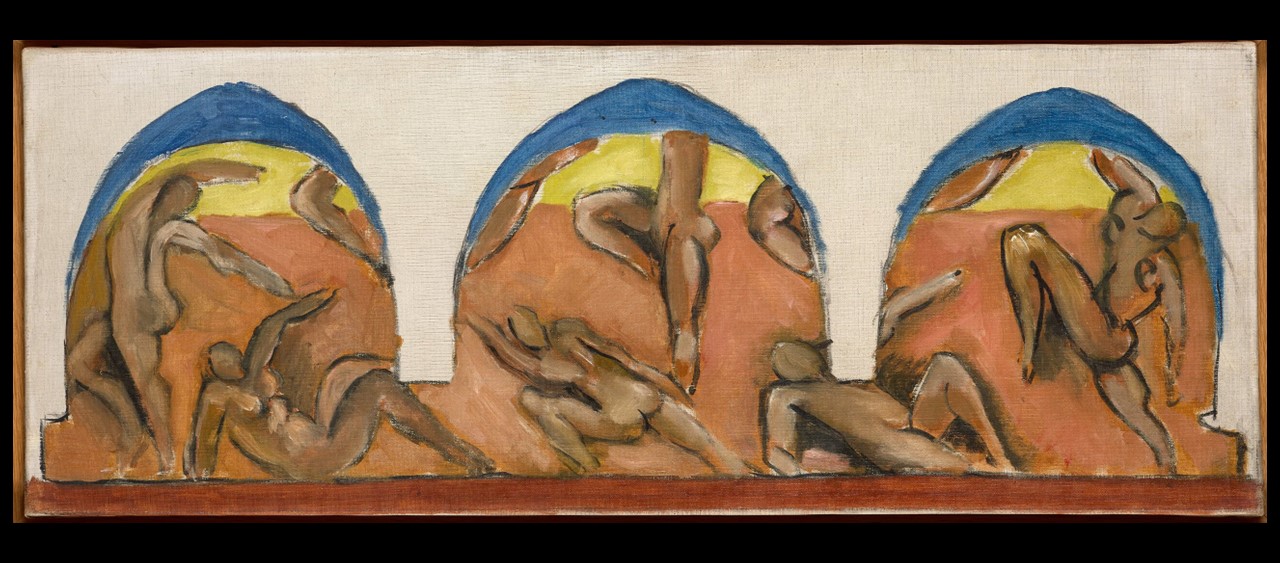

Study for Barnes Mural, Ocher Harmony, 1930–31, oil on canvas, 22×88 cm, Musée Matisse Nice, France

https://philamuseum.org/calendar/exhibition/matisse-1930s

‘Possessing’ the magnitude of the space he had to cover was his biggest challenge. Designing his dancers with correct proportions for the architectural space they would ‘inhabit’ was another one. Using large zones of flat colors that resist the typical illusion of depth and invite the Foundation’s viewers to gentle contemplation was yet, another.

Matisse experimented for a whole year… By using a long bamboo pole attached to a pencil as an elongated drawing device to sketch the dancers’ shapes, Matisse invented a new drawing tool. By cutting large pieces of pre-coloured paper and pinning them up, he solved the problem he faced of setting the piece’s correct proportions. For the first time, Matisse used scissors as an art tool, ushering in the age of his renowned cut-outs. He also began using a camera to document his process so he could compare changes from day to day.

The Dance in Philadelphia, at the Barnes Foundation, marked a return to a modernist style, ultimately creating a dynamic composition depicting bodies that seem to jump across abstracted spaces of pink and blue fields. Matisse struggled and changed the course of action many times, but in the end, ever so innovative, reached his goal and reclaimed his position as a leading figure in the tradition of decorative mural painting… to do it publicly and on a grand scale.

For a PowerPoint on the theme of Matisse and Dance, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.ias.edu/ideas/2016/bois-matisse-barnes and https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20230118-matisses-the-dance-the-masterpiece-that-changed-history and https://collection.barnesfoundation.org/objects/6967/The-Dance/