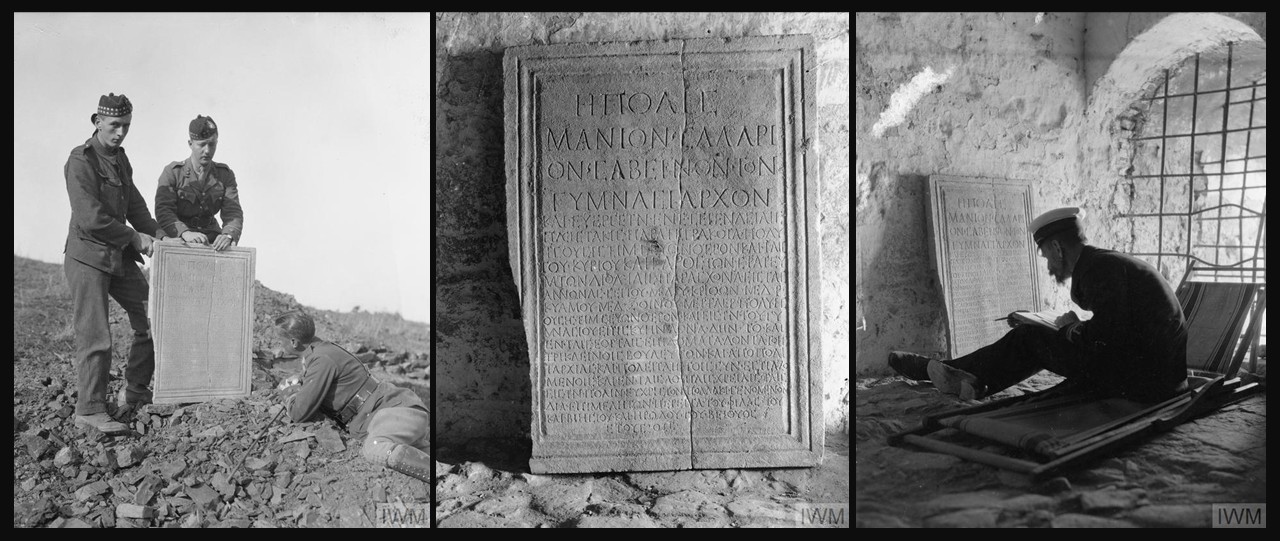

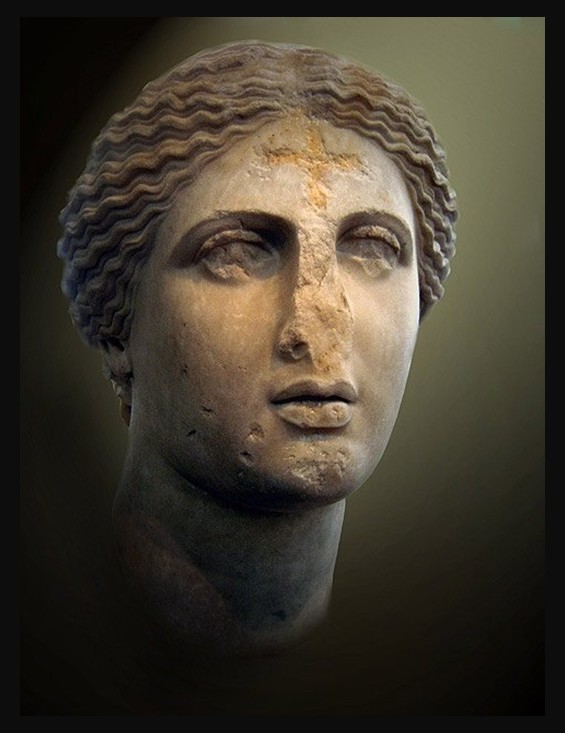

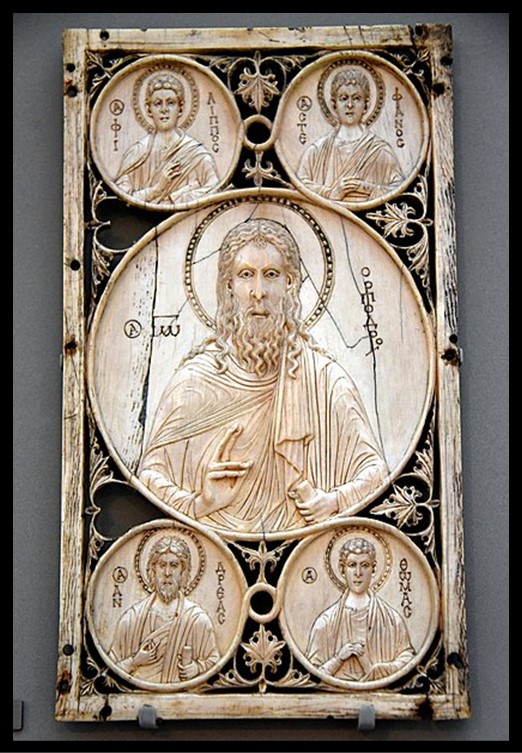

Ivory Angel fragment of a diptych valve, 6th Century, Ivory, Museum of Ancient Art in the Castello Sforzesco, Milan, Italy

https://www.alamy.com/ivory-angel-from-bottega-romana-fragment-of-a-diptych-valve-6th-century-museum-of-ancient-art-in-the-castello-sforzesco-sforza-castle-in-milan-italy-image223703517.html

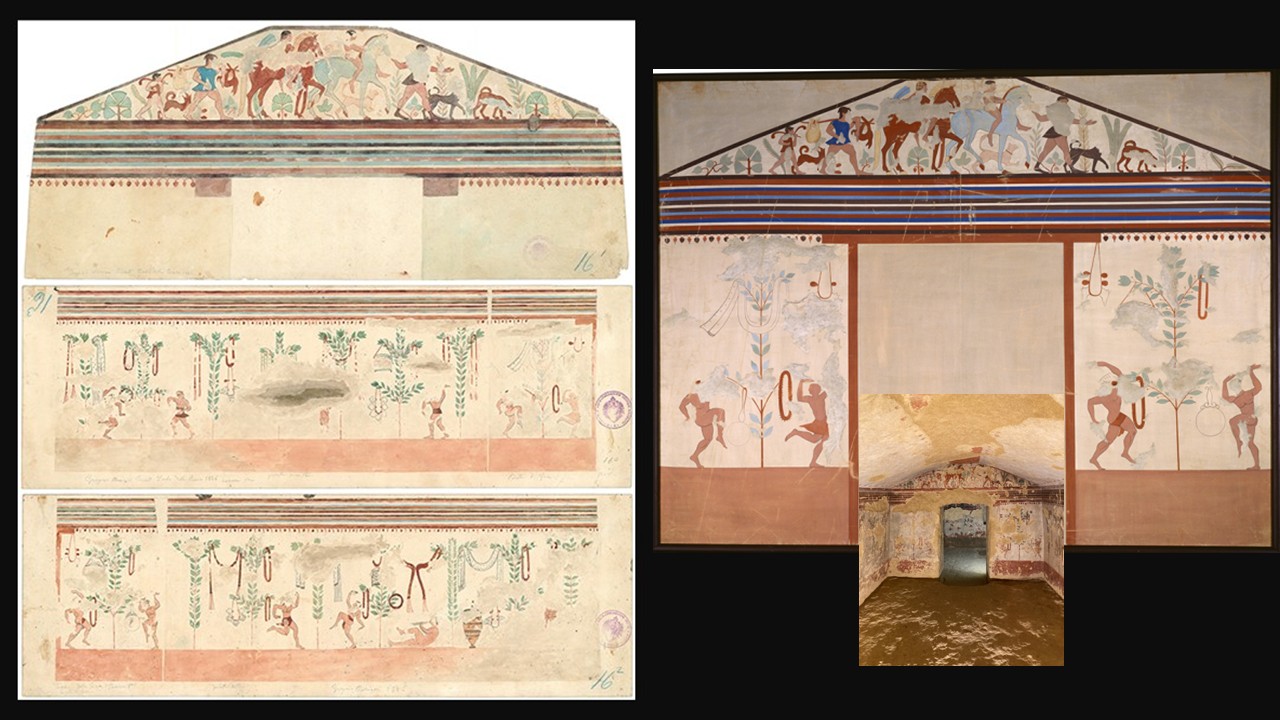

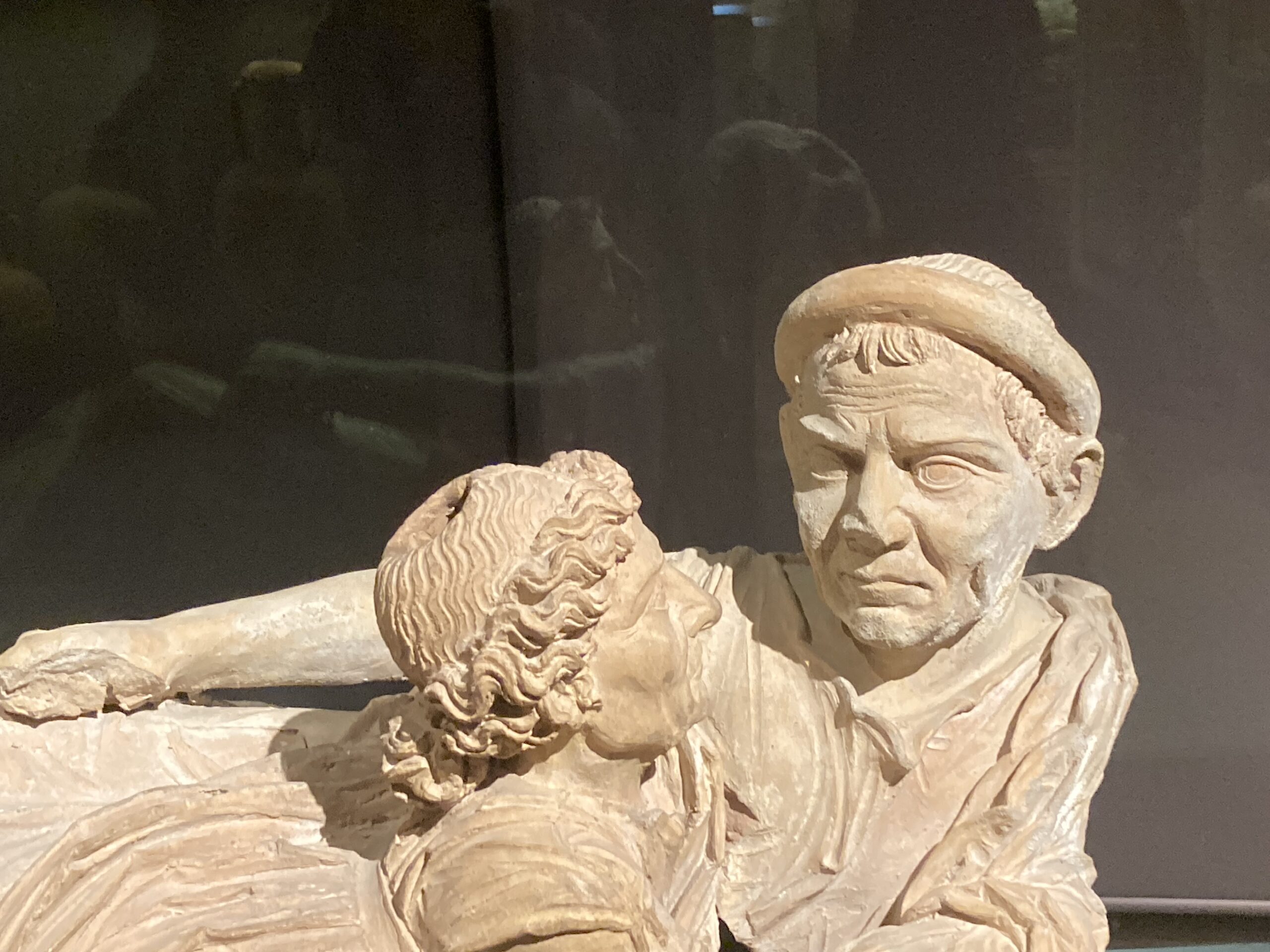

The Bargello panel of The Consular Diptych of Anicius Faustus Albinus Basilius (consul in 541 AD) offers a vivid glimpse into the ceremonial splendor and political symbolism of late antiquity. Carved in fine ivory, the plaque depicts the Consul Basilio standing frontally beside the personification of Rome, who crowns him with a laurel wreath, a timeless emblem of civic and military virtue. Below unfolds a chariot race, a rare and dynamic motif symbolizing the public games that marked the consul’s inauguration. The consul holds both the scipio topped with a cross and the mappa circensis, the cloth used to signal the start of the races, fusing Christian and traditional Roman imagery in a moment of political theater.

Once hinged to a now-separated companion leaf, the Milan panel (Avori 10, Castello Sforzesco), the Bargello relief would have formed one side of a luxurious diptych presented to commemorate Basilius’s consulship. The Milan fragment, showing Victory presenting the consul’s portrait within a clipeus, completes the scene’s message of divine favor and public virtue. Together, these ivories capture the final flowering of the consular tradition, bridging Roman civic ideals and Byzantine court aesthetics, and reflecting a world where art served both as devotion and as declaration of power.

Consular diptychs were luxurious paired ivory panels created in the late Roman and early Byzantine periods to commemorate the inauguration of a consul, one of the highest offices in the empire. Traditionally carved on the inside to hold wax for writing, these diptychs evolved by the 4th and 5th centuries into richly decorated ceremonial gifts rather than practical objects. Newly appointed consuls commissioned them to celebrate their accession and distributed them to friends, allies, and dignitaries as tokens of prestige and gratitude. The front surfaces were elaborately carved with scenes of the consul’s investiture, imperial imagery, or allegorical figures such as Victory or Rome, while inscriptions proclaimed the consul’s name and titles. Their iconography—often showing the consul presiding over games, dispensing largesse, or associated with divine favor—served to reaffirm the continuity of Roman civic traditions even as imperial power shifted eastward to Constantinople.

Anicius Faustus Albinus Basilius, consul in 541 CE, was a distinguished member of the ancient and influential Anicii family, one of the last great senatorial lineages of Rome. His career unfolded during a turbulent period in the Gothic War and the final years of the Western Roman aristocracy. Before attaining the consulship, Basilius held prominent administrative posts, including comes domesticorum (commander of the imperial household guard) and patricius, titles that reflected both his rank and his proximity to the imperial court. Appointed consul by Emperor Justinian I, he was the last man to hold the title in the Western tradition. After his term, the consulship ceased to exist as an independent civic office and became an imperial prerogative. His consular games, commemorated by the magnificent ivory diptych now divided between Florence and Milan, symbolized both the enduring prestige of Rome’s senatorial elite and the transformation of Roman political culture under Byzantine rule. Basilius’s life thus marks a poignant historical threshold: he stood at the end of Rome’s ancient civic offices and the dawn of a new, imperial order dominated by Constantinople.

The Consular Diptych of Anicius Faustus Albinus Basilius, divided today between the Bargello Museum in Florence and the Museo delle Arti Decorative in Milan, stands as one of the most compelling survivals of sixth-century ivory art. Created in 541 CE to commemorate Basilius’s consulship—the last in the Western Roman tradition—the two panels once formed a hinged pair, uniting political ceremony, imperial iconography, and refined craftsmanship. The Bargello panel represents the consul’s public and civic identity, while the Milan plaque embodies the divine and honorific aspects of his role, creating a complete visual narrative of authority and virtue.

The Bargello panel presents Basilius standing frontally in full consular regalia beside the personification of Rome, who crowns him with a laurel wreath, a symbol of victory and civic honor. In his hands, the consul holds the scipio topped with a cross and the mappa circensis, signaling the opening of the chariot races carved below in vivid relief, where teams of four-horse chariots turn around the spina of the circus. This combination of Christian and traditional Roman imagery reflects the fusion of old civic ritual with new imperial faith. The Milan plaque, by contrast, depicts a winged Victory seated on a globe, her feet resting on an eagle’s outstretched wings as she presents a clipeus containing Basilius’s portrait. Around it runs the inscription BONO REI PVBLICAE ET ITERVM (For the good of the Republic, and again), proclaiming the consul’s service to the state. Together, these compositions balance earthly power and celestial sanction, merging public ceremony with divine endorsement.

Aesthetically, the two panels reveal both unity and distinction. The Bargello panel is dense and narrative, crowded with human figures and architectural motifs that emphasize movement and civic spectacle. The Milan panel, in contrast, is more restrained and idealized, its composition centered, symmetrical, and imbued with spiritual calm. The Milanese Victory, delicately modeled and classically poised, recalls earlier Roman traditions of divine personification, while the Bargello figures are more rigid, their proportions elongated, their gestures formalized in the emerging Byzantine style. The difference in tone, public versus celestial, active versus contemplative, suggests that the two leaves were designed as complementary expressions of the same ideology: the earthly authority of the consul validated by divine and imperial favor.

Viewed together, the two ivories encapsulate the final synthesis of Roman civic art and Byzantine symbolism. They celebrate the consulship not merely as an office but as a sacred performance of continuity between past and present, Rome and Constantinople, man and empire. Their divided survival, one in Florence, one in Milan, mirrors the historical fragmentation of the world that produced them, yet their shared message endures: that power, piety, and artistic excellence could still converge in the twilight of antiquity. As such, the diptych of Basilius stands not only as a testament to individual glory but as a poignant farewell to the visual language of Roman public life.

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: Representing consulship: on the conception and meanings of the consular diptychs, by Cecilia Olovsdotter, OpAthRom 4, 2011, 99-124 https://www.academia.edu/11849854/Representing_consulship_on_the_conception_and_meanings_of_the_consular_diptychs_OpAthRom_4_2011_99_124?utm_source=chatgpt.com and https://catalogo.beniculturali.it/detail/HistoricOrArtisticProperty/0900645430