Byzantine Ivory Caskets, also known as covered boxes, represent exquisite examples of medieval artistry and craftsmanship. These small, intricately carved containers were crafted in the Byzantine Empire during the early medieval period, primarily between the 6th and 12th centuries. Made from luxurious materials such as ivory, these Caskets served a variety of purposes, ranging from holding religious relics to storing precious items like jewelry or cosmetics. Adorned with elaborate motifs, often depicting religious scenes, mythological figures, or intricate geometric patterns, Byzantine Ivory Caskets not only served functional roles but also conveyed the wealth, power, and artistic sophistication of the Byzantine civilization. These objects provide valuable insights into the social, cultural, and religious contexts of the Byzantine Empire.

In the present day, around 125 ivory Caskets endure, each bearing its unique journey through time and wear, with approximately 50 adorned in secular motifs. These elegant Caskets stand as a testament to Byzantine artistry, representing a remarkable legacy of secular expression preserved amidst the sands of time. Their survival marks them as the paramount example of Byzantine secular art, offering a glimpse into the aesthetic tastes and cultural nuances of an empire steeped in opulence and sophistication.

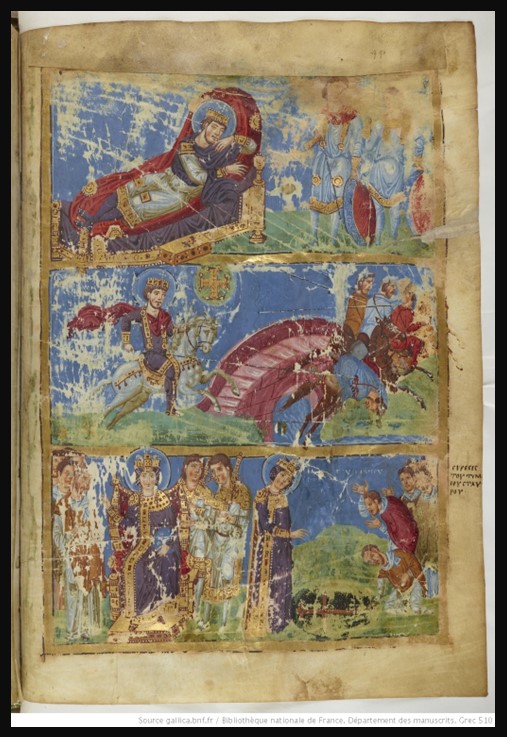

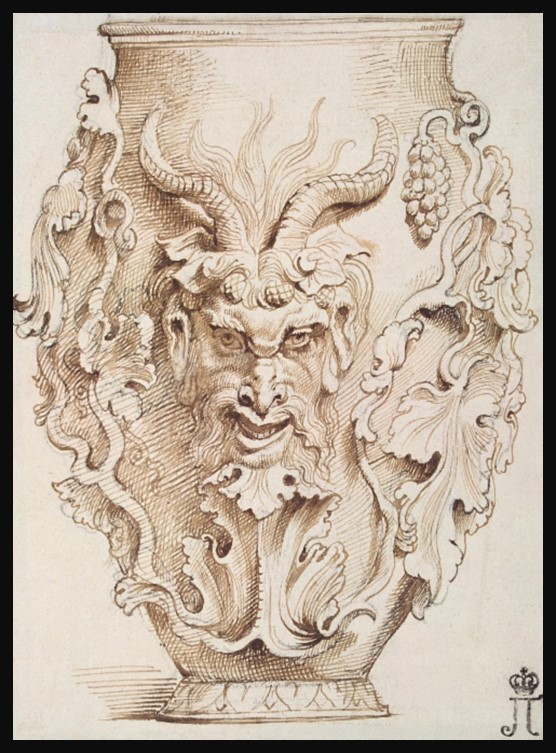

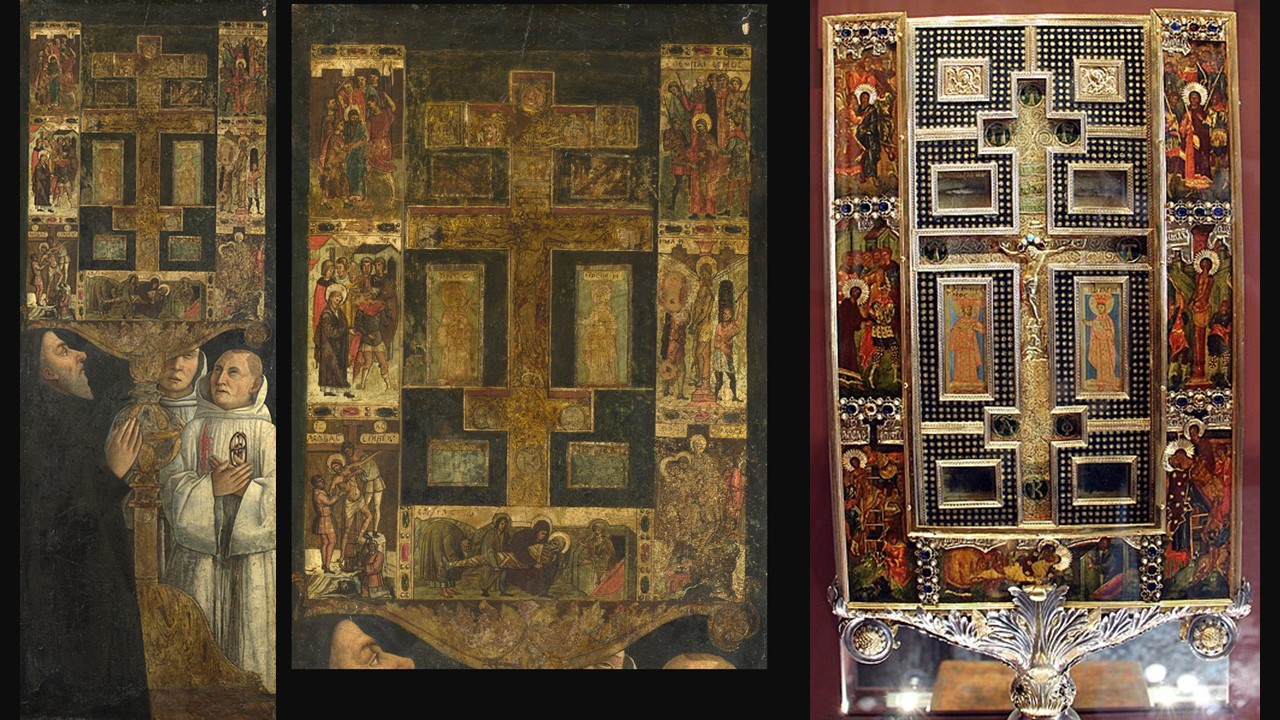

Intricately carved and made of transverse sections of elephant tusks, the Byzantine Caskets were more than mere receptacles; they were vessels of cultural significance and practical utility. Their intricate reliefs, often depicting a blend of pagan mythology and Christian iconography, hint at their multifaceted functions. Those adorned with scenes of Christ’s miraculous healings likely served as vessels for safeguarding the sacred elements of the Eucharist, underscoring their role in religious rituals and devotion. Conversely, Caskets embellished with pagan motifs might have been employed for storing personal effects like valuable documents, cosmetics or jewelry, reflecting the interplay between secular and religious spheres in Byzantine society. Though their precise origins remain elusive, scholars speculate that these Caskets were crafted in Constantinople or the Byzantine provinces of North Africa or Syria-Palestine, regions renowned for their ivory craftsmanship. Despite the enigma surrounding their provenance, Byzantine Ivory Caskets endure as tangible manifestations of the empire’s artistic prowess and spiritual fervour.

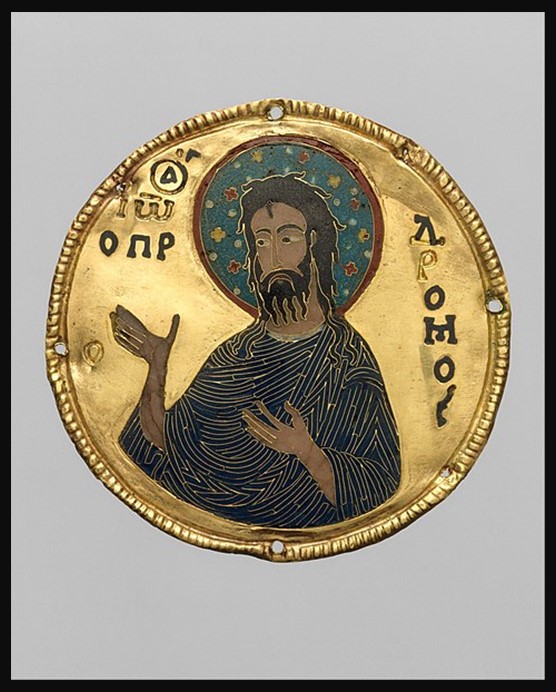

During the Byzantine period, ivory held a revered status as a symbol of luxury, prestige, and religious devotion. The Byzantines prized ivory for its exceptional beauty and workability, utilizing it in a myriad of contexts ranging from religious artefacts to secular luxury items. Ivory was extensively employed in the creation of intricate carvings, including religious icons, diptychs, and triptychs, which adorned churches, palaces, and private collections and Caskets as containers of precious secular or religious treasures. These exquisite ivory artworks served not only as expressions of faith but also as tangible manifestations of wealth and power. Furthermore, ivory was utilized in the production of practical items such as furniture inlays, game pieces, and personal accessories, reflecting its versatility and widespread appeal across various aspects of Byzantine society. The use of ivory persisted throughout the Byzantine period, leaving an indelible mark on the art, culture, and material wealth of the empire.

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=3555251714542348&set=a.547320410758138

Among these remarkable artefacts, the Byzantine ivory Casket of the Musée de Cluny in Paris stands as one of my favourites. Crafted in Constantinople around the turn of the millennium, this Casket is a testament to the refined tastes of the secular elites within the court of the Macedonian dynasty. Delicately adorned with finely carved ivory panels, it depicts intricate scenes drawn from the legendary exploits of Heracles and various other tales of Greek mythology to epic battles and chariot races. Each panel is a masterpiece of craftsmanship, capturing the essence of both ancient lore and medieval life. Undoubtedly intended for domestic use within the opulent confines of aristocratic households, this Casket serves as a tangible link between the classical past and the burgeoning cultural landscape of Byzantium.

As one marvels at this masterpiece within the halls of the Cluny Museum, one cannot help but be transported back in time, envisioning the opulence and splendour of the Byzantine era.

For a PowerPoint Presentation, please… Check HERE!