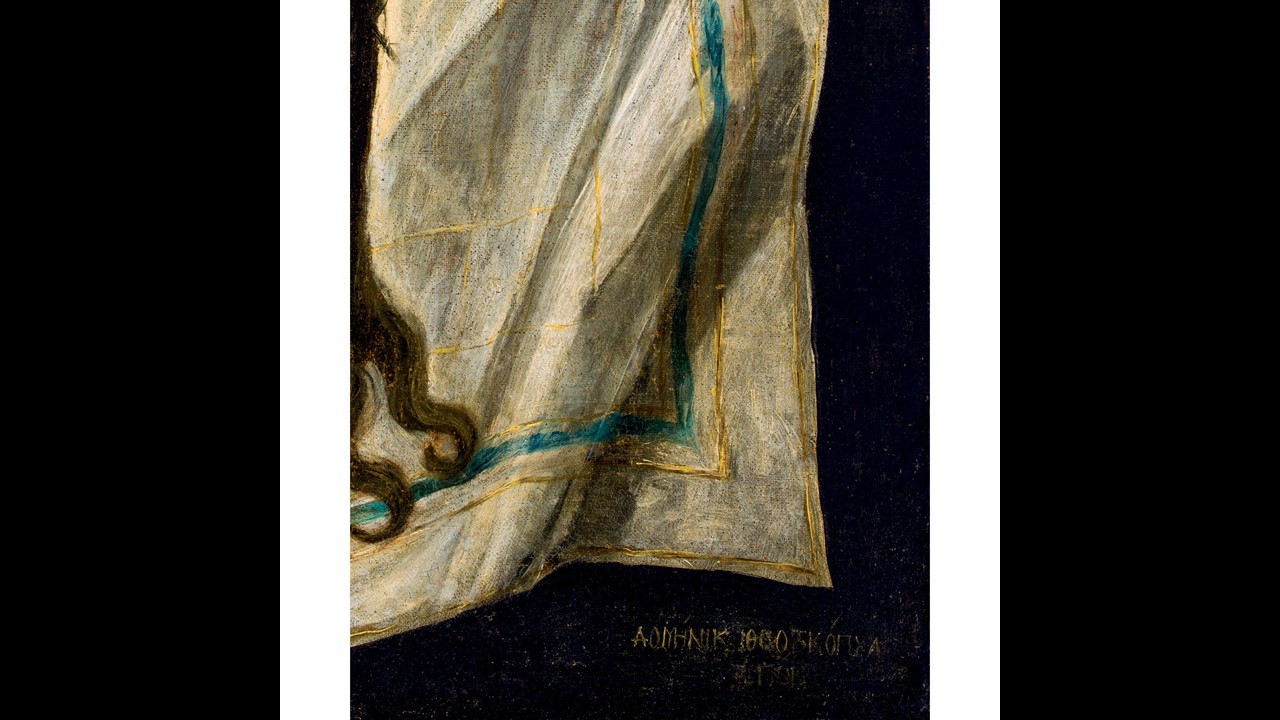

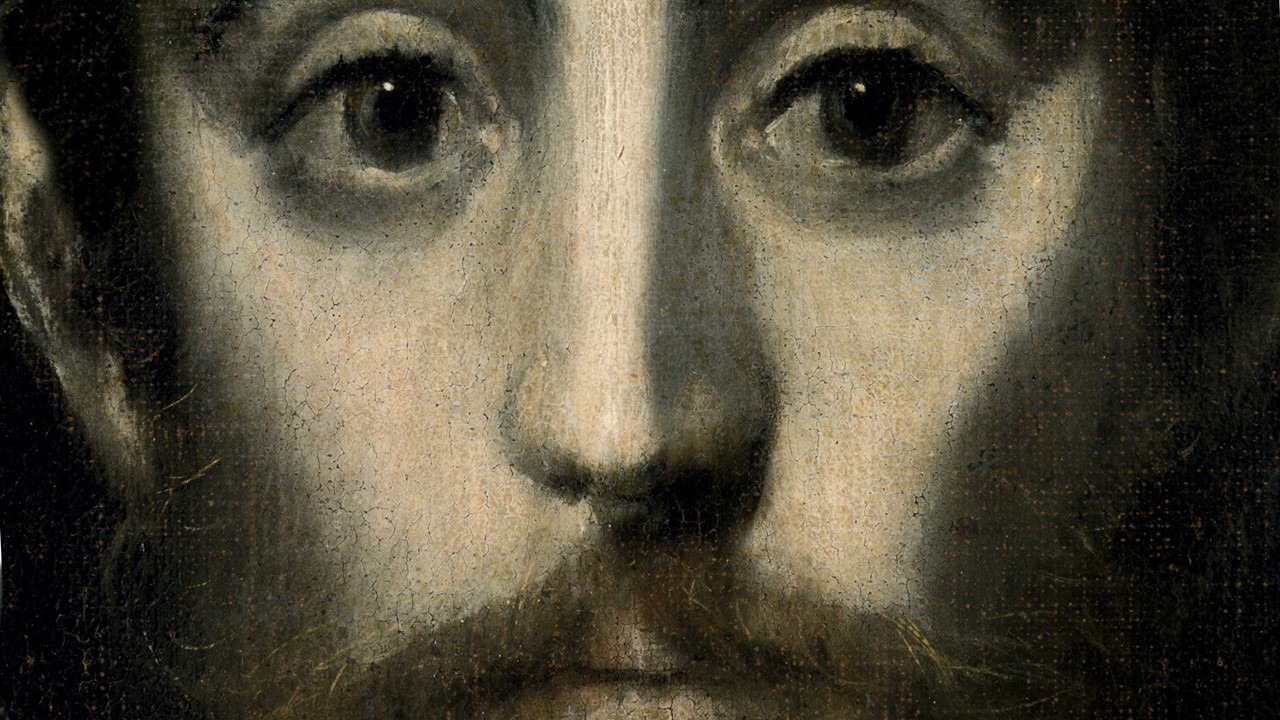

Virgin and Child, ca. 1520, Oil on wood, 25.4 x 21 cm, the MET, NY, USA

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436103

Lady, Our Lady, writes Vittoria Collona (Sonnet 51), did you not press and pour / into your milk, like essential oils wrung, / the whole of you, like living breath into lung, / to nourish the whole of your divine son? Or / did his living fire scorch your holy breast, and more, / breaking into pure light and pure song / the pieces of you like a universe born? / Who can understand it, how spirit tore / into the material world like lightning, / did not burn but lit it up in a flash / that lasted through the long night, whitening / like snow the dark, dark world? In the flesh / he came and defied every logic, not frightening / but consoling like the evening’s red flush… and I think of a lovely painting of the Virgin and Child in the Metropolitan Museum attributed to Simon Bening. https://aleteia.org/2022/08/14/is-this-the-most-beautiful-sonnet-ever-written-for-mary/

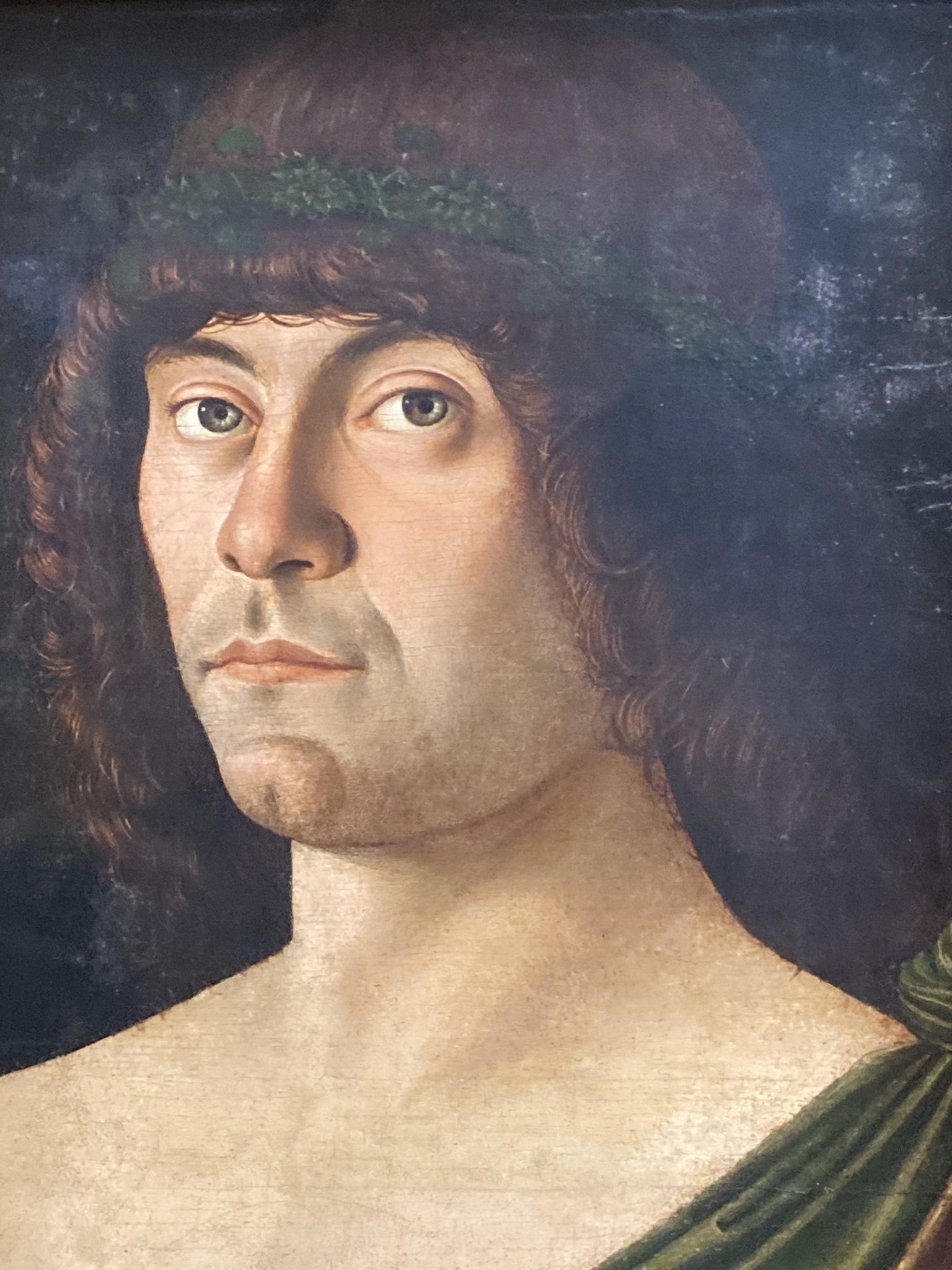

Self-portrait of Simon Bening, aged 75, 1558, tempera on parchment, 8.6×5.7 cm, the MET, NY, USA

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459254

Simon Bening is a master manuscript illuminator. Hailed by Portuguese art critic and artist, Francisco da Hollanda as the greatest master of illumination in all of Europe, Simon Bening was one of the most celebrated painters of Flanders in the 1500s. He served powerful aristocrats and worked for a group of international royal patrons including Emperor Charles V and Don Fernando, the Infante of Portugal. He is famous for creating some of the finest illuminated Books of Hours in the history of art. His specialty was painting, in the Flemish tradition, poetic landscape vistas… https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103JTN

The painting of the Virgin and Child in the Metropolitan Museum attributed to Simon Bening exhibits the painter’s interest in artistic exploration. According to the Museum experts, the artist of the Virgin and Child was heavily inspired by Gerard David’s painting depicting the Rest on the Flight into Egypt. Both paintings present the Virgin as the very model of a nurturing mother. The context is, however, different. David’s painting refers to the Gospels (Matthew 2:13-14) and the arduous journey of the Family to Egypt. Bening, if the Virgin and Child painting is indeed his, presents a ‘genre’ scene of a nurturing mother and child. From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 308-313 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/From_Van_Eyck_to_Bruegel_Early_Netherlandish_Painting_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art

Virgin and Child, ca. 1520, Oil on wood, 25.4 x 21 cm, the MET, NY, USA

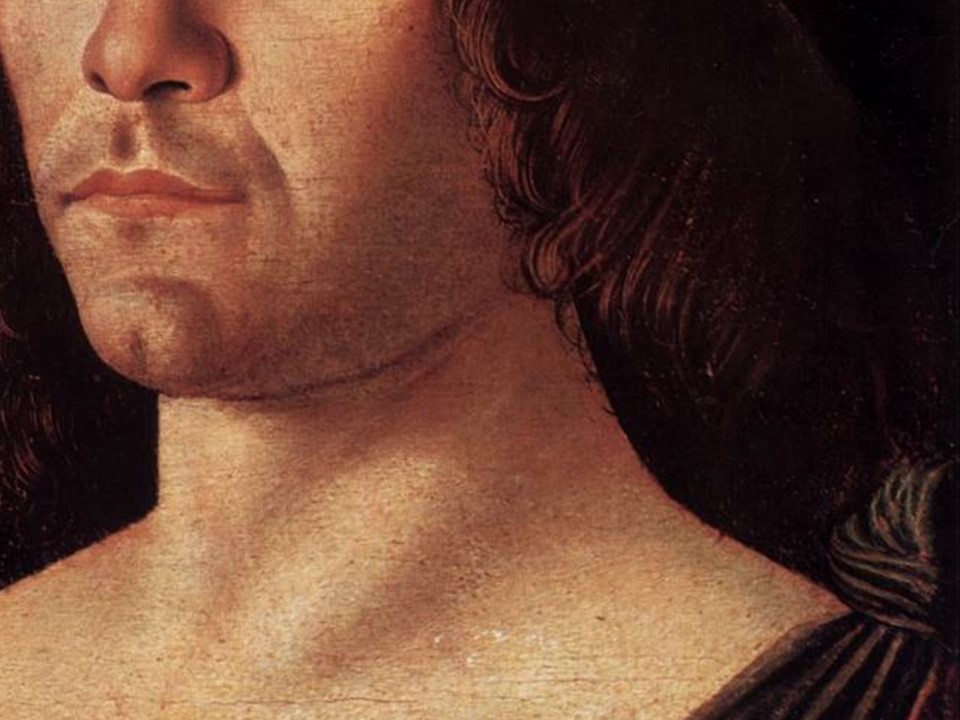

Gerard David, ca. 1455–1523

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, ca. 1512–15, Oil on wood, 53.3 × 39.8 cm, the MET, NY, USA https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436103 and https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436101

The MET painting of the Virgin and Child is typical of the Flemish tradition of ‘hidden’ symbolisms. Mary, for example, sits on the wall of an enclosed garden, the Hortus Conclusus, a symbol of her purity, which refers to the Garden of Eden of the Old Testament. Mint, present, in abundance, behind Mary, is a plant that grows wild in Palestine and is mentioned by Jesus in His discourse with the Pharisees. Bening uses it to further stress the virtue of Mary, as mint is a plant with healing and cleansing properties. The violets, at the lower part of the garden wall, are used by the artist as a sign of Mary’s humility. She is, after all, the Viola Odorata, meaning Our Lady of Modesty. Very important to underline is the stream of milk that flows from the Virgin’s breast to the lips of the Child, who turns to the viewer, spoon in hand, to directly communicate the notion of physical and spiritual nourishment. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/From_Van_Eyck_to_Bruegel_Early_Netherlandish_Painting_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art page 312

Simon Bening was famous for his poetic landscape vistas. His manuscript illuminations, like the pages of the Twelve Months in the Book of Golf we have been examining, reveal various aspects of his innovative character. The MET painting Virgin and Child favors a landscape that recedes into the far distance, large trees with highlighted edges, and the inclusion of a vignette… a small house surrounded by trees near the edge of a pond. This is a wonderful example of early sixteenth-century art for all to enjoy! https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/From_Van_Eyck_to_Bruegel_Early_Netherlandish_Painting_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art page 312

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!