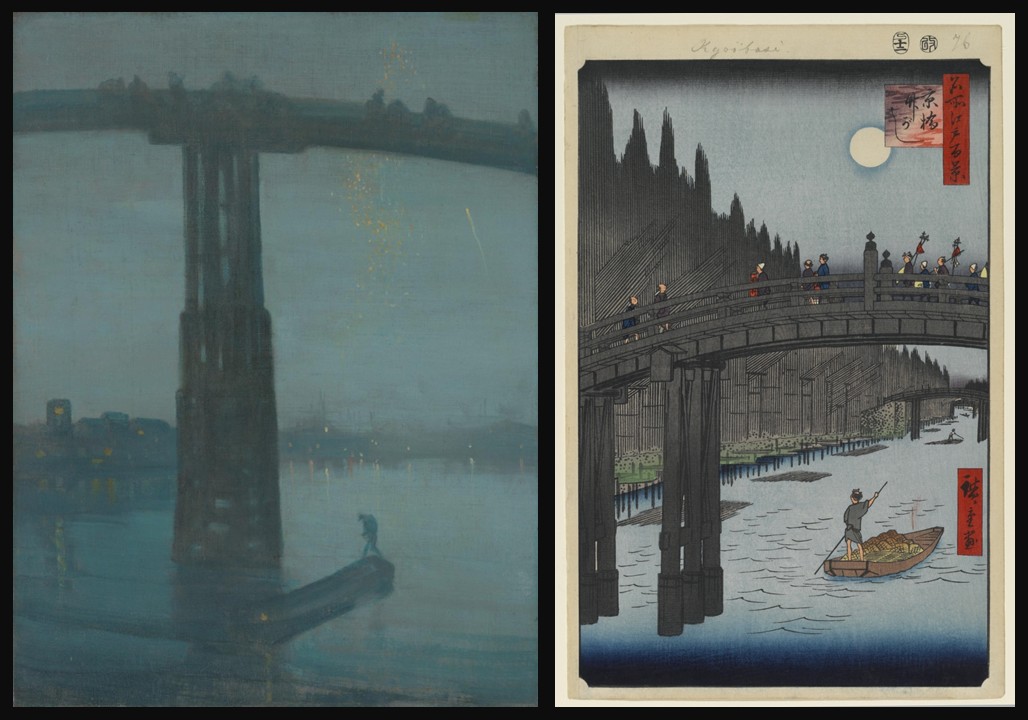

Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge, 1872, Oil on canvas, 66,6×50,2 cm, TATE Gallery, UK

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/whistler-nocturne-blue-and-gold-old-battersea-bridge-n01959

Utagawa Hiroshige, Japanese,1797-1858

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge (12th Month, 1857), from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, ca. 1856–58, Color woodblock print, 36×24.1 cm, The Art Institute, Chicago, USA

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/26522/fireworks-at-ry%C5%8Dgoku-ry%C5%8Dgoku-hanabi-from-the-series-one-hundred-famous-views-of-edo-meisho-edo-hyakkei

Bridges of Light – they often symbolize connection between places, people, or moments in time. In art, they also link the visible world to the realm of mood and imagination. Two works from opposite sides of the globe, James McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge (1872–75) and Utagawa Hiroshige’s Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge (1857), both turn the humble bridge into something poetic and transcendent. Though separated by culture, medium, and intention, they share an atmospheric stillness that invites reflection on light, water, and the human gaze.

James McNeill Whistler’s Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge captures London at night as a mysterious symphony of blue and shadow. Painted around 1872, this oil on canvas is part of Whistler’s celebrated “Nocturne” series, works that sought to translate the visual world into the language of music.

The scene is minimal: a great wooden bridge looms above the Thames, faint figures hover on its span, fireworks flicker faintly in the distance. Yet what dominates is not the structure, but the atmosphere, a veil of misty blue punctuated by golden glimmers. Whistler strips away narrative detail, emphasizing mood over subject. His soft brushwork and tonal harmony evoke a world on the edge of visibility, where city lights dissolve into the haze.

At the time, such abstraction was revolutionary. Critics like John Ruskin accused Whistler of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face,” prompting a famous libel trial. Yet today, this painting stands as a precursor to modernism, an early exploration of how color and composition can convey emotion without storytelling. Whistler’s bridge is not merely an urban landmark, it’s a threshold between reality and reverie.

Two decades earlier and half a world away, Utagawa Hiroshige portrayed another bridge, Kyōbashi, in the bustling city of Edo (modern Tokyo). His Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge (12th Month, 1857) is one print from the masterful series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, now in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

In this woodblock print, Hiroshige depicts a tranquil night scene: a full moon floats above a canal, wooden boats drift silently, and stacked bamboo poles line the riverbank. The bridge arches gently across the upper plane, connecting neighborhoods as the water reflects the glow of the winter sky. The composition is crisp and balanced, geometric lines meet fluid curves, and the print’s limited palette of cool blues and pale whites creates a luminous serenity.

Unlike Whistler’s subjective haze, Hiroshige’s clarity celebrates the harmony between city and nature. His mastery of linear perspective and color gradation (bokashi) guides the viewer’s eye into the depth of Edo’s nocturnal calm. The work belongs to the ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”) tradition, art that captured fleeting, beautiful moments of everyday life. Yet even here, amid bamboo yards and bridges, Hiroshige evokes something timeless: the poetry of stillness.

Though born of different worlds, Meiji-era Japan and industrial London, both works share an extraordinary sensitivity to atmosphere and light. Whistler’s oil painting and Hiroshige’s woodblock print each transform an urban bridge into a site of contemplation.

Whistler’s Nocturne immerses us in ambiguity and mood. His blues blur edges and forms, inviting emotion over clarity. Hiroshige’s Kyōbashi Bridge, by contrast, sharpens detail within calm order. Yet both convey the quiet beauty of the city at rest, a pause between day and night, motion and stillness.

There is also an intriguing link between the two artists. Western painters like Whistler were profoundly influenced by Japanese art during the late 19th century, a movement known as Japonisme. Whistler himself admired Hiroshige’s prints and adopted their compositional daring: asymmetry, flattened perspective, and the focus on atmospheric tone. In a sense, Whistler’s London nocturne owes a debt to the poetic precision of Edo’s floating world.

In both images, light and water serve as mirrors, literal and symbolic. Hiroshige’s canal reflects the moon’s glow, while Whistler’s Thames glimmers with distant sparks. Each artist invites us to linger in that reflection, to sense the beauty that lies between visibility and suggestion.

The choice of medium also shapes the experience. Hiroshige’s woodblock print, with its clean contours and delicate color transitions, feels crafted, meditative, and reproducible, designed for an audience that cherished everyday beauty. Whistler’s oil painting, on the other hand, is singular and subjective, the result of layered pigment and a painter’s improvisation. Both reveal how material and method can express different kinds of intimacy with the world.

Bridges are not only physical crossings but metaphors for transition, between places, cultures, or even states of mind. In Nocturne in Blue and Gold, Whistler transforms London’s industrial river into a space of mood and mystery. In Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge, Hiroshige turns Edo’s night into a vision of harmony and calm.

Viewed together, these two works form a quiet dialogue across continents. One whispers through mist, the other gleams under moonlight, yet both remind us that art’s greatest power lies in its ability to make the familiar shimmer anew.

For a PowerPoint Presentation on James McNeill Whistler’s art and Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints, please… Check HERE!

Bibliography: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/whistler-nocturne-blue-and-gold-old-battersea-bridge-n01959 and https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/objects/121690