The Bronze Horses of San Marco, 1876, Oil on Canvas, 102.2 × 82.6 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art, USA

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_Caryl_Coleman_-_The_Bronze_Horses_of_San_Marco,_Venice_-_79.13_-_Minneapolis_Institute_of_Arts.jpg

I read Brenda Riley-Seymore’s poem on The Horses… Don’t cry for the horses that life has set free. / A million white horses, forever to be. / Don’t cry for the horses now in God’s hands. / As they dance and prance to a heavenly band. / They were ours as a gift, but never to keep / As they close their eyes, forever to sleep. / Their spirits unbound, forever to fly. / A million white horses, against the blue sky. / Look up into Heaven. You will see them above. / The horse we lost, the horse we loved. / Manes and tails flying, they gallop through time. / They were never yours, they were never mine… and I think of The magnificent Bronze Horses in San Marco… and imagine them… dance and prance to a heavenly band… https://www.horsesofhope.org/horses/tribute-to-first-horse

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quadriga#/media/File:Horses_of_Basilica_San_Marco_bright.jpg

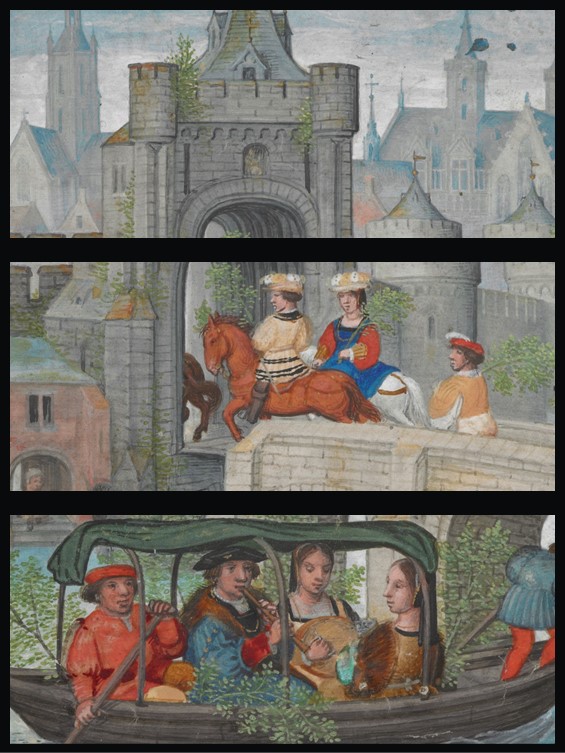

The bright bronze quadriga came to Venice as part of the rich war plunder gathered by the Venetians, under doge Enrico Dandolo, after the conquest of Constantinople at the end of the 4th Crusade in 1204, together with other works of inestimable value, many of which are still housed in the Basilica’s Treasury. The Quadriga is magnificent, and the introduction by the experts of the Basilica di San Marco in Venice was enlightening. The Quadriga story is that of admiration, greed, plunder… and artistic inspiration… http://www.basilicasanmarco.it/basilica/scultura/la-decorazione-delle-facciate/quadriga-marciana/?lang=en

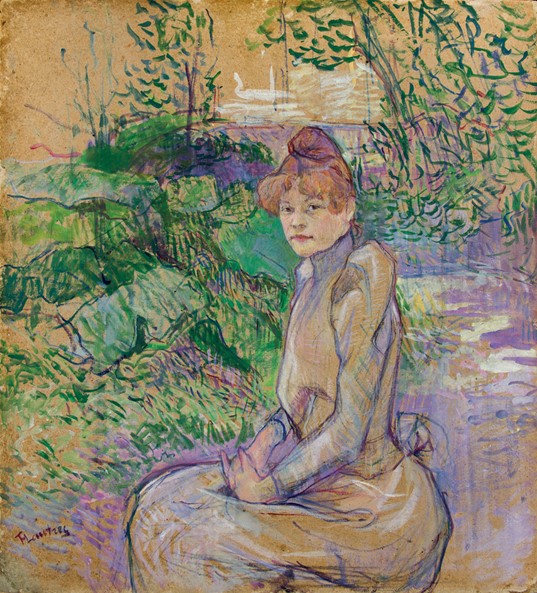

Charles Caryl Coleman is according to the Smithsonian experts, a decorative and genre painter who has been largely overlooked by the American art community since his death. He studied art in New York, and later, in Paris, under Thomas Couture. He served with the Union during the Civil War and established himself as an artist by exhibiting his work, regularly, at the Boston Athenaeum, the Brooklyn Art Academy, and the National Academy of Design. Early in 1867, he moved to Italy and rarely looked back. There, he joined a vibrant, international community of artists that included Vedder, Maitland Armstrong, William Graham, Thomas Hotchkiss, Frederic Leighton, Giovanni (Nino) Costa, and other artists in the circle of the Macchiaioli. In 1876, while in Italy, Colemanfinished his pivotal painting, titled The Bronze Horses of San Marco. https://www.aaa.si.edu/blog/2019/08/charles-caryl-coleman-rediscovered

Coleman’s painting of San Marco’s Bronze Quatriga is, I believe, one of the finest painted representations of Venice’s magnificent treasure. The artist depicted the bronze horses as they stood on the porch of the Basilica of San Marco, using foreshortening, and displaying an unusual diagonal perspective for his composition. Placing the bronze horses on the central/right side of the painting, he was able to add a refreshing view of the upper section of the Piazza’s monumental Clocktower in all its decorative glory. Cool tones of paint, restrained brushstrokes, and the artist’s love of the decorative, combined with fine art created a painting that greatly exemplifies Coleman’s qualities as a leading artist of the International Aesthetic Movement. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/2607/the-bronze-horses-of-san-marco-charles-caryl-coleman

For a Student Activity, please… Check HERE!